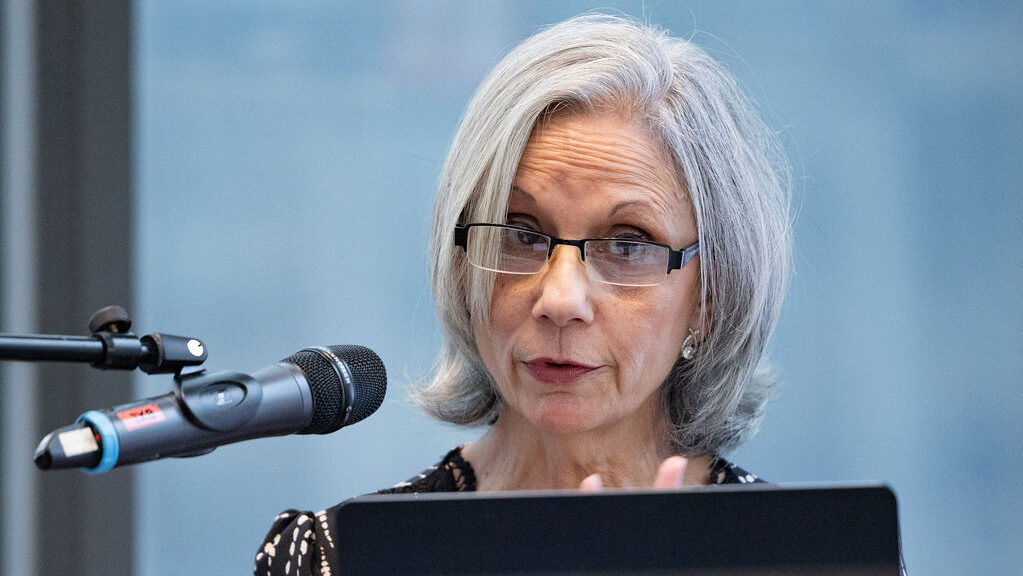

Sary Levy‑Carciente

Ievgeniia Pavlenko

“The best response to the violence is not hatred, but the daily courage of those who continue to believe that ideas are fought with other ideas. Never with violence.”

Sary Levy‑Carciente, a Venezuelan economist and a Hernando de Soto Fellow at the Property Rights Alliance, is one of the most prominent voices in institutional and economic analyses of property freedom. She is currently a Senior Research Scientist in the Adam Smith Center for Economic Freedom and is the author of the International Property Rights Index (IPRI) 2025. Her work examines the link between institutional stability, human development, and innovation. In this edition, which covers 93 % of the world’s population and 98 % of global GDP, the report reveals a trend of erosion in property‑rights protection worldwide—and Europe is no exception.

The index places Luxembourg, Australia, and Switzerland at the top, while the United States continues to lead globally in intellectual property. However, the European bloc shows signs of fatigue: setbacks in innovation, excessive bureaucracy, and a tax system that penalises investment. In Levy‑Carciente’s words: “Innovation does not flourish in environments where risk is punished and freedom is regulated.”

Trained in institutional economics with more than two decades studying the foundations of prosperity, Levy‑Carciente has turned the IPRI into a global reference. Her diagnosis of Europe is clear: the continent has built a strong legal framework, but its increasing regulatory density and fiscal pressure are suffocating private initiative. In this interview with europeanconservative.com, she examines the structural causes of the technology gap between Europe and the United States, and outlines the reforms needed to recover lost dynamism.

First, that we are seeing institutional weakening. For the second consecutive year, the index reflects a decline in political and legal stability, and that directly affects respect for property. We thought that after the pandemic, this cycle had been overcome, but no: bureaucratisation continues to grow, which prevents property rights from being realised in an agile way. You can have very firm laws, but if the administrative system blocks them, the right ceases to be effective.

The European Union is well-positioned overall, with an aggregate score of 6.9—only behind Oceania—but most European countries declined in intellectual property, with some exceptions, such as Czechia or Slovenia. That is worrying, because intellectual property is the engine of the knowledge society and innovation. If that pillar weakens, Europe runs the risk of being left behind in the technological transformation era.

Very significantly. Excessive regulation is perhaps the Achilles heel of the European model. Not only because it slows processes down, but also because it also creates uncertainty. I’ve heard many entrepreneurs say that environmental regulations, for example, have become a form of public intervention that limits their productive capacity. A livestock farmer told me, “If I can no longer exploit a third of my land due to climate restrictions, how stable is my property right?” That sense of legal insecurity erodes confidence, and without confidence, there is no investment.

Taxes are another way to attack property rights. In Europe, the fiscal burden is high and uneven. There are countries where the tax load shoots up and ends up disincentivising entrepreneurship. The tax‑adjusted IPRI shows reductions of up to 12 % in some states. That means the taxpayer sees his ability to invest, to innovate, and to generate employment diminished. Property ceases to be an incentive and becomes an obstacle.

Because innovation requires risk. In the United States, venture‑capital funds understand that failure is part of the process: seven out of ten projects don’t reach the market, but that does not stop them. In Europe, on the other hand, failure is penalised. Welfare has been confused with comfort, and stability has become inertia. Without a culture of risk, productivity does not grow, and wages stop improving. Innovation is the true engine of progress, not subsidy.

Yes—Israel is one of them. It did not become a startup nation’ just by having good universities, but by accepting risk as part of the system. They even rewarded those who had failed before: if you had tried to innovate and had not succeeded, you had a higher chance of receiving new funds. That creates an ecosystem where creativity multiplies. There are also examples within Europe, such as Estonia, which has de‑bureaucratised its administration, or even Ukraine, which, in the middle of a war, is implementing very bold digital reforms.

First, simplify. Europe needs less legislation and more economic freedom. Second, guarantee legal stability without falling into hyper‑control. Third, promote venture capital, reward innovation, and stop penalising success with excessive taxes. The key is to create an environment of trust. When people perceive that their rights—to property, to entrepreneurship, to freedom—are protected, society as a whole prospers.

Absolutely. The Western world has a strength that cannot be bought or imposed: freedom. Spaces of freedom generate creativity, innovation, and prosperity. Authoritarian regimes may be efficient in the short term, but they lack that genuine source of development. That’s why I always repeat: true creativity emerges in freedom.