Metropolitan Opera productions by Sir David McVicar have become so routine, so predictable, and generally so gray and grim that their recurrence evokes Soviet Five-Year Plans. The Eleventh McVicar, as it were (the Twelfth and Thirteenth McVicars will be imposed next season), emerged on February 28, after the company returned from a month-long hiatus put in place to minimize mid-winter dips in sales: historically, February has been the Met’s least visited month. This time, Giuseppe Verdi’s expansive grand opera Don Carlos was left to Sir David’s tender mercies.

That we normally call Verdi’s opera Don Carlo (without the “s”) indicates the new production’s major point of interest. For reasons that have not been fully explained, the Met decided to present the opera with its original French libretto by Joseph Méry and Camille du Locle instead of the revised Italian version of the opera in near-universal use. Verdi composed Don Carlos for the Opéra de Paris, where it premiered in 1867. He later revised the work substantially for the Italian stage; its edition of 1884—retitled Don Carlo—is regarded as definitive, with only a handful of efforts to restore the French version popping up over the past two decades.

There may be an argument here for historical authenticity in a genre that has embraced a curatorial ethos in a grasping effort to remain relevant. The Met considers the French version different enough that it bills Don Carlos as an altogether new addition to its repertoire—the performance I attended on March 3 was announced as the company’s “second,” even though Don Carlo has been performed in the house—in Italian—since its company premiere in 1920. The Met’s multilingual electronic subtitle system does not include the French text, nor is the French libretto offered for sale in the Met’s gift shop.

Despite the company’s plea for originality, the plot of Don Carlos differs in no way from that of the familiar Italian version. Adapted from Friedrich Schiller’s play Don Karlos, Infante von Spanien, Don Carlos is a grossly fictionalized dramatization of an episode in the long reign of Spain’s sixteenth-century King Philip II (1556-1598). Philip’s son, the title character, falls in love with the French Princess Élisabeth de Valois, who was originally Carlos’s intended bride but was then married off to his father to secure a peace treaty. Carlos also rebels against his father Philip over his brutal treatment of the people of Flanders, who were then revolting against Spanish rule. Overshadowing both the personal and the political is the looming power of the Spanish Inquisition, personified by the Grand Inquisitor, a pitiless, blind, 90-year-old cleric whose power is ahistorically portrayed as greater than that of Spain’s monarch.

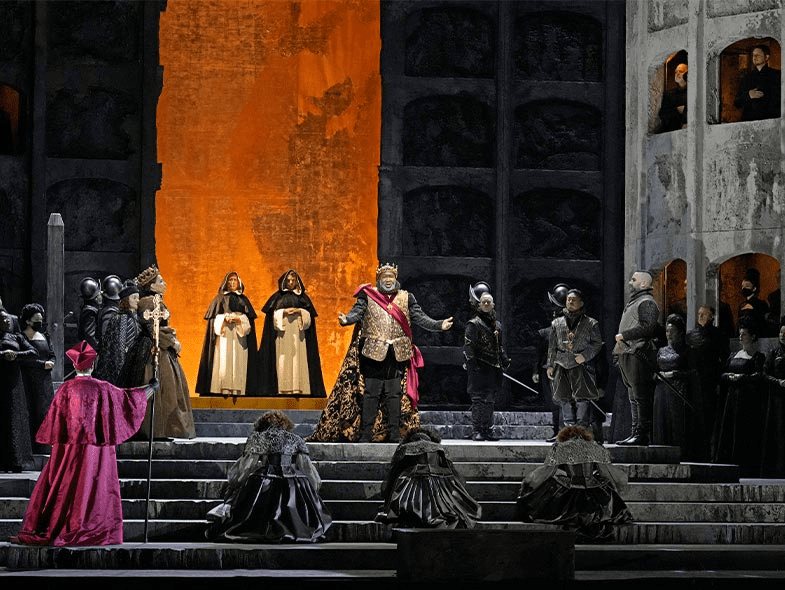

In the denouement, Carlos’s plans are foiled thanks to the betrayal of his best friend Rodrigo, whose loyalties are torn, and by Philip’s mistress Princess Eboli, who had in turn loved and been spurned by the young prince. Removed from the world in time, he is, depending on the direction, either killed or dragged into a monastery by a spectral monk who may be his grandfather, the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who had abdicated to religious life in 1556. In McVicar’s oppressive production, which relies monotonously on gray and imposes a sepulchral semicircular set resembling the crypt of the Escorial Palace, where Philip lives and broods, Carlos is mortally wounded and awkwardly welcomed into the afterlife by the embrace of Rodrigo, who also does not survive the drama. Set against the production’s dismal sets, the action unfolded as a five-hour dirge of funereal hopelessness before ejecting spectators into equally gray Manhattan surroundings where after-theater conviviality is long dead.

It took the intrepidity of my friend and colleague George Loomis to piece together what elements of the original Paris version were included and which revisions remain in place. For all the curatorial effort on display, there is only selective fidelity to the opera’s original 1867 version. All of its original music is well documented, but only some passages were selected for inclusion in this production while others were left out. The most glaring omission was the ballet, a signature requirement of Paris Opera productions in the mid-nineteenth century—and the one that famously tripped up Richard Wagner when the Paris version of his opera Tannhäuser premiered disastrously just six years before Don Carlos. Leaving out the dancing was a missed opportunity. Titled “La Peregrina,” after a pearl that belonged to generations of queens of Spain and later Elizabeth Taylor (whose dog famously chewed on it), Don Carlos’s ballet figures among Verdi’s finest dance sequences and is still occasionally remembered on concert programs, if almost never in operatic performance.

On the other hand, most of the unfamiliar material that was included adds nothing to the work and only reminds us why Verdi later revised the opera. To take only the most obvious example, a rebellious scene in which a violent crowd is cowed by the frightening entrance of the Grand Inquisitor now includes Carlos’s improbable rescue. The Inquisitor’s appearance also redundantly humbles Philip, who has already been browbeaten into conceding the primacy of the Catholic Church in his spooky confrontation with the prelate, which is one of the most compelling musical-dramatic scenes in all of opera. Moments like this made it hard to get a sense of the editorial principles at work—if, indeed, there were any.

Restoring the French libretto proved another letdown. Consider Philip’s mournful Act IV aria lamenting Élisabeth’s lack of affection for him. In French it begins “Elle ne m’aime pas”—“She doesn’t love me,” which sounds far less profound than the Italian “Ella giammai m’amò,”—“She never loved me.” The difference is not subtle. While the Italian conveys deep emotional investment, existential angst, and wounded betrayal, the French suggests merely the cerebral processing of an unfortunate situation. Élisabeth’s cries for “Justice” when her affections for Carlos are exposed sound pettier than the disaster that lurks behind her Italian counterpart’s cry for “Giustizia.” And a courtier who just saved his king from mortal harm would probably be happier rising in rank to the proclamation “Marchese, duca siete!” rather than simply being informed, “Marquis, vous êtes duc.” These are only three instances in which the familiar Italian version is far more expressive and satisfying.

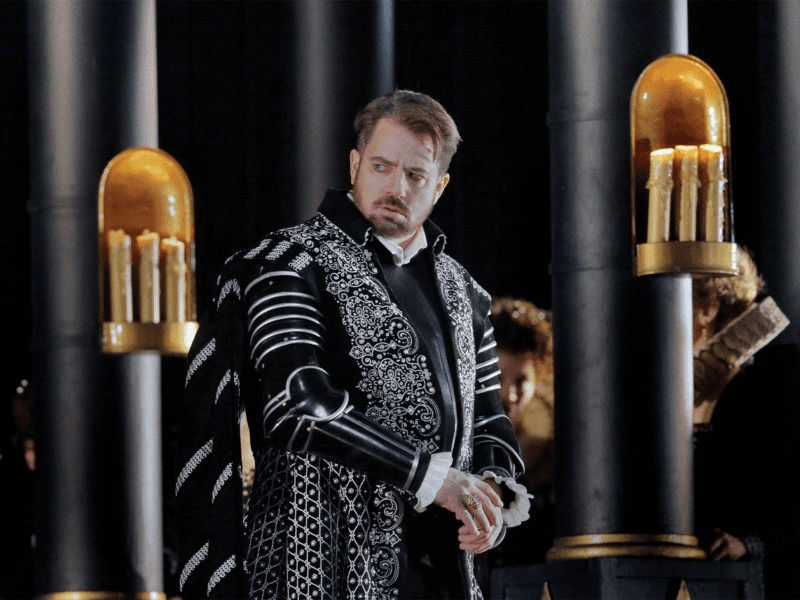

Good musicianship overcame these deficiencies to some degree. Matthew Polenzani is a solid tenor and an accomplished Mozartean, but he seemed rather out of his depth as Don Carlos. The voice has a warm and endearing quality, but the part’s raging adolescence and emotive rebellion requires a squillo sound that he could not command sufficiently to impart any sense of thrill. Sonya Yoncheva started a bit timidly but swelled in volume and virtuosity as the evening progressed. By the final scene, which includes her major aria “Toi qui sus le néant” (again, more abstract than the Italian “Tu che le vanità”; vanity is much closer to our human experience than nothingness), her blooming middle register offered Golden Age appeal. Rodrigo was wisely entrusted to the young French-Canadian baritone Étienne Dupuis, who gave a stentorian performance despite a faintly ridiculous costuming job. Jamie Barton’s Princess Eboli was impassioned without falling victim to the stridency that often intrudes on the role. Amanda Woodbury resounded as the celestial voice in the auto-da-fè scene.

In the lower register, the performance suffered from Eric Owens’ gravely Philip, which sounded better (in Italian) four years to the day before this performance, when I heard him sing the role with some success for Washington National Opera. John Relyea’s Grand Inquisitor was loud and mean, but did not quite master the lowest notes in the way that the truly great exponents of the role have done.

Met music director Yannick Nézet-Séguin conducted Don Carlo to considerable acclaim at the Met over a decade ago. Returning to the work in this new version, he took a broad and authoritative approach to the score, including its unfamiliar elements. Sometimes he explored the nuances at the expense of the overall sonic architecture, but he drew an overall estimable performance from the Met’s orchestra and chorus.

Although the curatorial gestures barely merited the effort, there was some political relevance. At the premiere on February 28, the performance was preceded by a rousing performance of Ukraine’s national anthem by the chorus and orchestra, with Met general manager Peter Gelb musing without much historical insight that Russia’s invasion of that country recalled the worst excesses of the Spanish Inquisition as depicted in the opera. The previous day, the Met had announced that it would end relationships with artists who support Vladimir Putin’s government and those who are supported by it.

By the time of the performance I attended a few days later, this policy extended to Russian artists who would not actively denounce their government, regardless of their personal sentiments and the serious potential consequences facing all Russians who do so. When superstar soprano Anna Netrebko, arguably the only remaining singer on the Met roster who could still command a sell-out audience, failed to make the required declaration of faith, it was announced that she had “withdrawn” from her scheduled performances this season and next season. Gelb stated in a separate interview that he saw no realistic way for her ever to return to the Met stage. In the glum atmosphere that hung over the house, more than one spectator might have wondered who the Grand Inquisitor is now.