The German philosopher Walter Benjamin (1892–1940) once said that to understand an idea, one must understand its extremes. This applies above all to an ambiguous and philosophically dense idea like beauty.

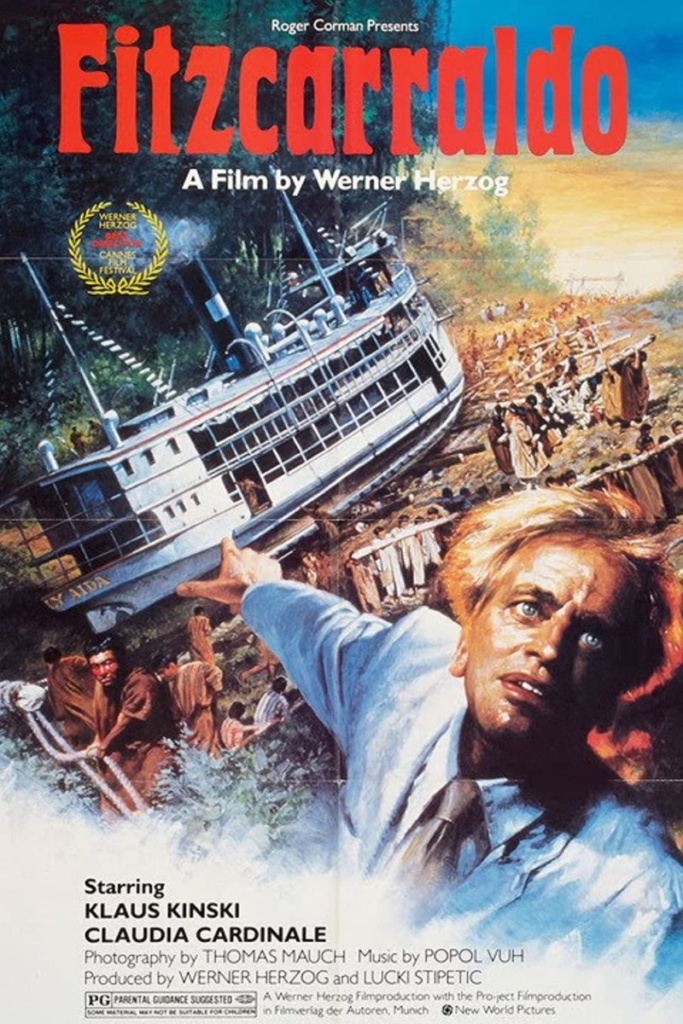

Western culture has ovulated to an extreme sensitivity to both art and beauty, expressed in a climate of political correctness. Therefore, it would be almost uncontroversial to state that a modern form of iconoclasm is occurring in the West. Let me take the story of Werner Herzog’s 1982 Fitzcarraldo as a striking example of the crusade against raw beauty.

After World War II, a new generation of German filmmakers sought to make its way in a devastated and divided country. Together with Wim Wenders and Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Werner Herzog revolutionized post-war German cinema. In a post-modern era, when pre-eminently the great stories seem impossible, Herzog inimitably tells the ultimate epic of Fitzcarraldo.

Fitzcarraldo tells the story of a blond European man who has fallen in love with the city of Iquitos and the dense forests and winding rivers of the Peruvian Amazon. Building his own opera in the heart of Peru is everything Brian Sweeney Fitzgerald, nicknamed Fitzcarraldo, dreams of. The Egon Schiele-like figure, invariably adorned in ivory linen costume, is brilliantly played by the now-vilified Klaus Kinski. He has no money for an opera, and after a failed ice factory and countless attempts to convince investors, Fitzcarraldo throws himself into the mining of rubber. With a refurbished steamboat and a crew of Peruvian howlers, he undertakes a journey to the darkest recesses of the Amazon forest. They sail upstream on the Ucayali River, a journey no Westerner has ever ventured before. Fitzcarraldo has an iron will and an even greater vision. He is as misunderstood as he is chaotic, but undoubtedly mesmerizing. Klaus Kinski is the mysterious, charming rubber god he plays.

Not only Kinski, but all the actors have been cast with the utmost sensitivity and attention to detail. The actors’ distinct appearances make extended dialogues unnecessary. The captain looks like a captain, and the rich rubber barons look like rich rubber barons. Herzog chooses to tell his story through ironclad cinematography. Despite the mostly short and fragmented scenes, the script preserves enough harmony to convey the story in a clear, yet artistic way. It is here, then, where Herzog truly excels. In addition to being a filmmaker, he is a storyteller and a poet.

However, while everything about the story is epic, the making of it is perhaps even more so. Herzog, as a true Bavarian, makes cinema without compromise, and today that leads to an increasingly large number of calls to cancel his work. The protagonist’s problematic history, combined with Herzog’s alleged treatment of Peruvian extras and the various deaths that occurred on set, all contribute to the maligned nature of one of the greatest epics in recent film history.

Instead of canceling this film, I advocate celebrating it, as a sign of creativity and artistry without political compunctions. Werner Herzog shows us what are the possibilities of film on a limited budget. Far away from the big, politically-influenced movie studios and the pricey sets, one of the most iconic German films ever was made. From the acting to the set design and cinematography, everything about Fitzcarraldo captures the imagination. The experience of the film is akin to watching an opera, but more than that, Fitzcarraldo is reminiscent of a corrida in the blazing Madrid sun. Herzog balances brute force, spectacle, and intensity with an over-romantic finesse and sensitivity. But like the corrida, Fitzcarraldo no longer quite fits the Western zeitgeist. The problematic way in which the film was made and the allegedly racist overtones that can be found in some scenes would be difficult for much of today’s audience to stomach. Filmmakers like Herzog are a rare breed and a head-on collision between complete artistic freedom and an oversensitive society seems inevitable for them. The stark conclusion is that by 2022, Fitzcarraldo would no longer be made.

While one might argue that this contributes to the uniqueness of works of art, any conservative mind can only disagree pertinently. Hypersensitivity forces beauty into a politically-correct straitjacket, one that becomes stricter to comply with day after day. It is hardly surprising that such straitjackets kill beauty, for what cannot breathe, cannot live.

At one end of the political spectrum, art and beauty are said to be celebrated, but find themselves undeniably in an existential crisis. The eulogy is given when artists come up with ‘socially critical’ works of art. Artworks that mock God and religion, address refugee issues, or impose a progressive ideology are welcomed with open arms; works of art that truly challenge the eye and the mind of the beholder, on the other hand, are deemed shocking and out of place. Art is standing on its final legs when it can only be shown to those wearing the correct political glasses. The point being made is not a new one, but it must continue to be stressed.

To complete the circle, I return to the beginning of this article; when we renounce in advance any attempt to arrive at a clear understanding of any of the extremes, an idea will never be understood. Western sensitivity brings the arts in Western Europe and America to the verge of their demise. Let art justify her own existence, in lieu of letting politics do it in her place.