Parenthood is intimidating in the best of times, and these are not the best of times. As the 21st century nears the turn into its second quarter, the West is beset by social unrest, rising racial tensions, polarization, and tragic sexual and familial dysfunction. We have experienced a frightening pandemic and isolating lockdowns, food shortages and skyrocketing costs of living.

In my own country, statistics show that our institutions command very little trust; nearly half of Americans say they have “very little” or “no trust” in each of the following: big business, the criminal justice system, TV news, newspapers, congress, and the presidency. Meanwhile, the public school system, banks, organized labor, and the Supreme Court can each only muster less than 30% of people to admit to having “a great deal” or “quite a lot” of confidence in them. Where do we turn in times like these?

For many, including me, part of the answer lies in adherence to a religious tradition. Religion—particularly in the form of the three best-known monotheistic faiths of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—promises the faithful that they can live in accord with God’s will regardless of the state of the world. In my own tradition, we are taught that the faithful are to be a light to the world, showing Christ’s love to all we meet, and that even our suffering—if offered humbly to God in union with the Crucifixion—can bring us fulfillment and growth towards Him.

There is something firm, something solid, about clinging to inherited truths and attempting to form our children’s lives around them. And yet, as not a few people have noted before me, children grow up. They have free will, and they are offered many possible ways to live; this is particularly true in recent centuries.

Perhaps the quintessential Hollywood treatment of these themes is Fiddler on the Roof, the 1971 musical film adaptation of the stage show of the same name that opened 60 years ago this month. Fiddler takes place in Russia and follows Tevye, a devout Jewish man, who lives with his family in a small village in the early twentieth century. While the film and stage show are widely beloved—and criticized—many do not know that they are based on a series of Yiddish short stories that interrogate the same themes with a more deft and subtle hand than one would expect.

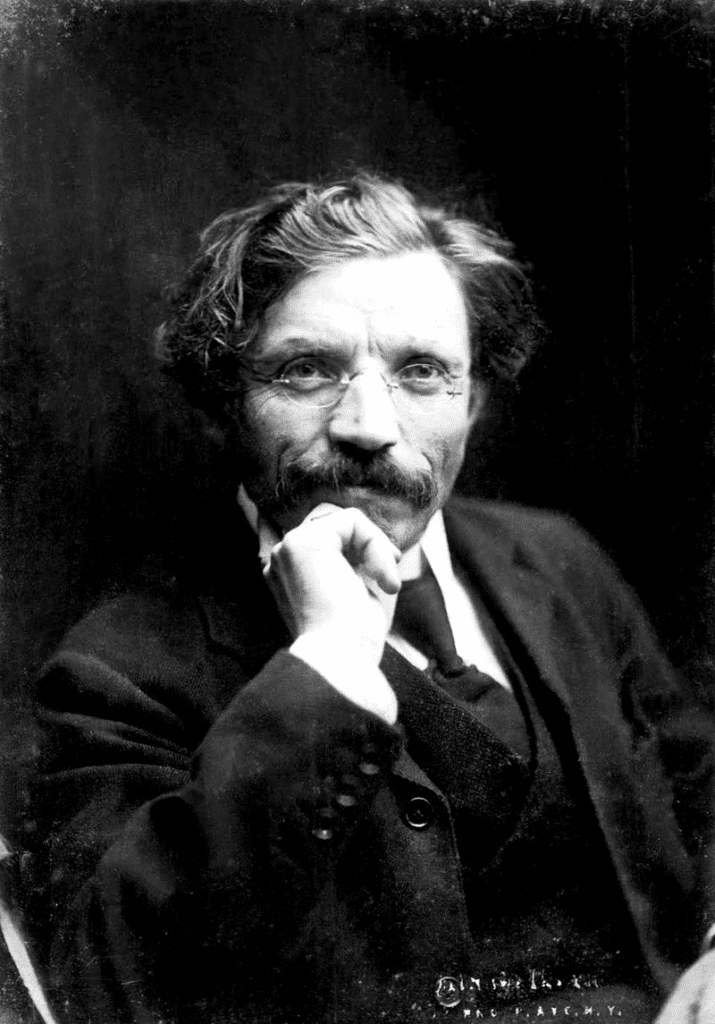

But before discussing the stories, it’s useful to begin with their author, Solomon Naumovich Rabinovich (1859-1916), who published them under the pen name Sholem Aleichem. Aleichem grew up under the Russian empire in what is now Ukraine. He was given a good Jewish education in his early years. However, his father was a follower of the ‘Jewish Enlightenment,’ and made the somewhat unusual choice to send his son to a non-Jewish Russian high school.

This dual formation—in traditional Jewish religious thought and in modern Russian literature—would prove decisive for Aleichem. He dreamed of becoming a writer who would elevate modern Jewish literature to the heights of the Russian masters. He initially attempted this in Hebrew and Russian, but, in the 1880s, Aleichem began composing in Yiddish, which is when his greatness began to show itself. As Dante had done with Italian, Sholem Aleichem helped to legitimize a language that was often thought of as simply unfit for serious literary work. However, there is another writer to whom Sholem Aleichem is often compared: Mark Twain.

One reason for this comparison is obvious: as Samuel Clemens took on the mantle of Mark Twain, so Rabinovich published mainly under a pseudonym. Another similarity becomes apparent on examining the function the latter’s assumed name plays in his work. The pen name Sholem Aleichem literally means, “Peace upon you!” in Yiddish and Hebrew. At the time, it was used as a rather casual greeting, equivalent, perhaps, to our “How’s it going?” or “Good to see you!” Using a commonplace greeting as a name helped communicate that his works, though aiming at literary excellence, were not lofty and inaccessible, but approachable. Like Twain’s works, they often focused on everyday folks, generally either living in poverty or at least setting up their tents within striking distance of it.

Sholem Aleichem was not merely a pen name, though. He was, in a sense, a character in his own right. As Dan Miron explains, “Common, folksy personae were rife in Yiddish writing of the time,” but “Sholem Aleichem, crafted as a whimsical, clever, high-spirited, but quite unruly and unpredictable vagabond, caught the imagination of the readers as did no other persona.” One might think of a Yiddish Douglas Adams or Kurt Vonnegut, commenting upon each story as he told it. He was so beloved that, on his death in 1916, mourners filled the streets of the New York City neighborhood where he had been living.

While many of Aleichem’s works seem to be simple comedies of manners, the author worked to integrate his evolving vision of the world into them. Politically and philosophically, Aleichem’s early life was marked by a certain liberal idealism married to a passionate Zionism. However, after witnessing myriad political failures, he became disillusioned with … well, just about everything. The Tevye stories are marked by this shift; the earliest, written in the late 1890s, are far more lighthearted than those written later. But I’m getting ahead of myself; we should discuss the tales themselves before considering this point.

Aleichem’s most beloved work is a series of short stories collected into a book called Tevye der milkhiker, literally “Tevye the Milkman,” but sometimes released in English as Tevye and His Daughters. The book, like Fiddler on the Roof, centers on the life of a poor Jewish man named Tevye, and it, too, allows tragedy and comedy to sit side-by-side in this man’s life. Perhaps most crucially, both the book and the musical force readers to confront the conflict between traditional ways of life and modernity.

While most of the major plot points and themes from the musical are rooted in the stories, readers are often surprised by the original literary version. Aleichem’s Tevye, like the Tevye of the musical, is a pious patriarch who is deeply connected with the traditions of his people and who regularly references Scripture. But, as Dan Miron puts it, he “resembles Sholem Aleichem’s original creation no more than a beautified postcard resembles the reality of a foreign city.” While I personally have great affection for Fiddler on the Roof, there is no denying that it is quite sentimentalized, something that can’t be said of the stories.

The stories are all in Tevye’s voice, meaning we are getting a rather one-sided account of events, but there is no indication that the man is anything other than a reliable narrator. Tevye spins his tales for Sholem Aleichem himself (who, the fiction goes, is passing it on to us), and he is often remarkably self-effacing. For instance, in the first work in the series, before telling the story of receiving a financial windfall, Tevye says that “A stroke of good luck doesn’t take brains or ability.”

The earliest stories are the most comical, but they have a melancholic character to them. There is a sense that Tevye’s life is not in his control. He is not well-to-do, and he has sired only daughters, a pair of circumstances that, in his world, meant great hardship. As the stories progress, his identity as the father of many daughters comes to the forefront, with four increasingly tragic tales about his children. After losing most of his family members, Tevye is ultimately forced to leave his home.

Some great works are easy to talk about, while others resist comfortable discussion. The Tevye stories, for me at least, are an instance of the latter. They are beautiful, funny, and heartbreaking in equal measure; they are thematically complex; crucially, they are deeply informed by modern Judaism, a religion I hold in high regard but do not myself practice. As a result, I cannot pretend to have any power to elucidate the texts—I can only share some of how reading these powerful works impacted me.

When reading of Tevye’s life, especially his difficulties in helping his daughters to find good lives rooted in their ancestral religion, I naturally think of my own role as a father. It is tempting for me to hold the stories at arm’s length. Tevye, after all, lived in a time when modernity was far less excruciatingly advanced, when most parents assumed their children would simply continue to live as their fathers and forefathers lived. Religious parents today are far more aware of how much pressure the world will exert on their children to leave the faith for lives of dissipation, or at least spiritual emptiness. Thus, I try to make Tevye’s stories safe, saying that I will be able to inoculate my children against the dangers of the contemporary world.

Tevye’s stories remind me that I am not the all-powerful ruler of my children. I cannot create a perfect little world where they can play in the garden freely with no fear of snakes. There is evil in this world, and it is aggressively targeting children today in myriad ways. I cannot change this reality.

Now, none of this means that I need to be foolish. Just because I cannot completely protect my children doesn’t mean I should throw my hands up in defeat. I have no need to, for instance, give them devices with 24/7 access to the vilest pornographic material imaginable; my children won’t be getting smartphones or tablets anytime soon. There are things that I can do to instill piety, restraint, and a sense of wonder in my children, but they are, at the end of the day, creatures with free will.

I am thankful for the gift of faith, a gift my mother passed down to me. I am particularly thankful to have been formed in a religion that has many traditions and rituals associated with it. These concrete practices help us to connect with God and remember him in very tangible ways, ways that are particularly powerful for young children. What Christian child does not see the beauty in the Christmas tree, the evergreen that, like Christ, maintains its vitality through even the darkest times? And what Catholic child doesn’t get excited for the blessing of throats on St. Blaise’s Day or the blessing of animals on the feast of St. Francis? In addition to being conduits of beauty and meaning, they are also inoculations against an overweening modern secularism that flattens out the depths of man’s spiritual nature and divine calling. Like many like-minded religious parents, I try to provide my children with copious time outdoors, timeless books, religious education, and experiences of the arts.

But weren’t Tevye’s children raised in a similar way? Admittedly, their education wouldn’t have had the kind of intentional emphasis on beauty and the reading of secular poetry that my children’s does, but even so. Their observance of the Sabbath, for instance, would have been far stricter than my family’s celebration of the Lord’s Day. And they had a much stronger community than my wife and I can hope to cobble together in our day. It would be hubris to claim that I can be sure to raise perfect children by the sheer power of my own will. At the end of the day, my final recourse is not to any claims to power over them; it is, like Tevye, prayer for them.

If, God willing, my children grow up to be kinder, holier people than I am, I will rejoice. But if some or all of them bend to the ways of the world, I can do little more than Tevye himself: I can put one foot in front of the other, do my duty, try to care for my family, and love my God.