Elijah in the Desert (1818), a 125.1 x 184.8cm oil on canvas by Washington Allston (1779–1843), located in the Museum of Fine Arts Boston.

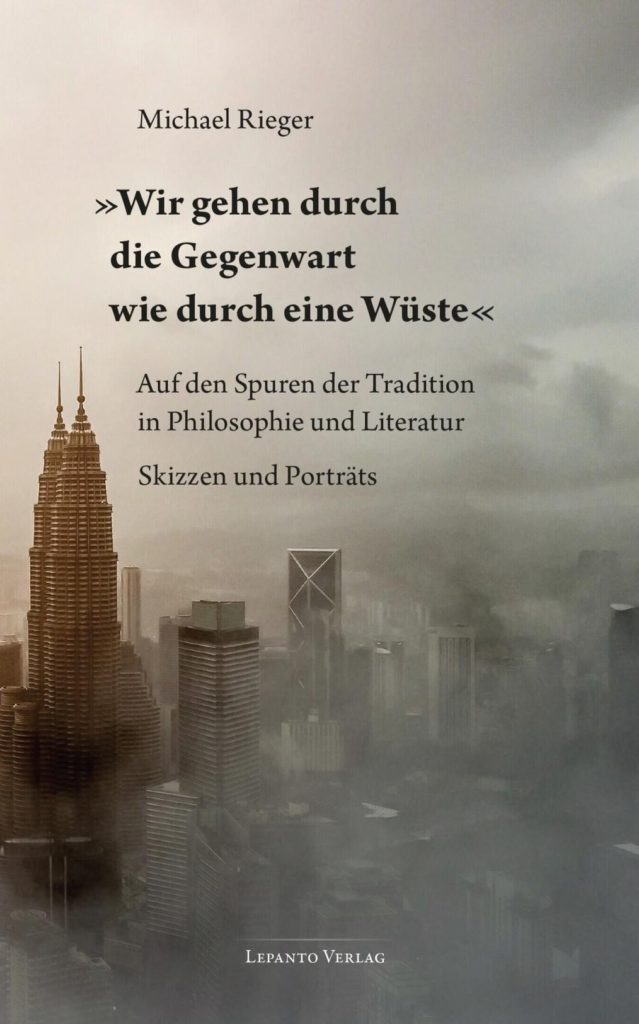

It is not uncommon to see a quotation serve as the title of a book. But it is rare today to see a quotation by a little-known, almost forgotten author—one held to be a staunch monarchist and reactionary—serve as the title of a book. However, both the quote at the beginning of the book’s title (which means “We go through the world like a forest”) and its author (Othmar Spann) fit this book quite well, for Michael Rieger here offers a portrait of various philosophers and writers, all of whom faced a modern world which appeared to them like a desert, especially when compared to the richness of the past and its traditions.

It is, however, one thing to simply describe a given state of affairs and quite another to be uneasy with it and try to somehow correct mistakes and misconceptions. That this book is an example of the latter alternative is immediately apparent from the quotation used in its title. Spann’s basic message was that if the loss of culture is an empirical fact in the history of mankind, so is the ability for us to overcome that loss. But accomplishing this requires offering something more substantial than the spiritual emptiness, economism, functionalism, mechanism, materialism, consumerism, and secularism of the present.

That ‘something’ cannot be more modern because that would only deepen the crisis. Rather, it must be something that resists modernity, something that comes from antiquity, from Christianity, from the Middle Ages. Rieger points to the example of Reinhold Schneider. When the National Socialists seized power in Germany, Schneider advocated for a return to the past, a return to tradition. He was confident that this was the source of the fundamental values needed to save Germany.

From the desert of modernity, therefore, there is a path, and that is the path of tradition and return—that is, in the spiritual sense: as in the soul’s return to God. One does not have to participate in despair. The world can be recaptured, and one can conquer what the world is and what it represents. As long as there are remnants of tradition, it is possible to reject the modern madness and to offer instead a different image, a different form, a different value system.

Rieger’s book—which is subtitled On the Spurs of Tradition in Philosophy and Literature: Sketches and Portraits—is about those who have remained on that path of tradition and faith. It is about the signposts, norms, and forms that could serve such people, even today. Indeed, many of those portrayed by Rieger are contemporary writers—men like Martin Walzer, Peter Handke, Botho Strauss, and Martin Mosebach, to name a few. The longing to renew tradition and faith in the face of modern decadence remains current because power is always connected with a transcendental, supernatural source, and their separation always brings with it a malaise and a despair that compels man to respond.

The same point can be put another way: together with Rieger and Wilhelm Röpke, we may ask: “Of what avail is any amount of well-being if, at the same time, we steadily render the world more vulgar, uglier, noisier, and drearier and if men lose the moral and spiritual foundations of their existence? Man simply does not live by radio, automobiles, and refrigerators alone, but by the whole ‘unpurchasable’ world beyond the market and turnover figures, the world of dignity, beauty, poetry, grace, chivalry, love, and friendship, the world of community, variety of life, freedom, and fullness of personality.”

Conservative literature, says Rieger, reminds us of a far wider and deeper reality that stands in the teeth of the unification and banalization of the modern world. And the authors in his collection show that “conservative literature emerges only where it escapes the optional,” where “it connects us with images of the past, with nature and with what lies behind nature,” for “it is the literature of the primary.” As such, it is a literature of resistance—resistance to what Benedict XVI called the “dictatorship of relativism.”

The 16 articles that constitute this collection have previously appeared in conservative magazines, especially in the bimonthly Sezession. They are organized into four parts. The first deals with the opposition between Catholicism and modernism; the second with debates about interwar Germany; the third with the work of Reinhold Schneider; and the last mostly covers the postwar critique of modernity. All in all, it is a wide arc that starts with Karl Ludwig von Haller, continues through the aforementioned Spann and Schneider, and ends with Heidegger, Martin Walser, and Peter Handke.

The main target of the authors’ critique, according to Rieger, is the loss of the “connection between faith and being,” followed by the unbridled individualism, atomization, selfishness, narcissism, materialism, and economism that characterize the present. This culminates in the arrogance of one who does not want to know anything but himself. Yet a subject preoccupied primarily with himself and his rights can hardly appreciate the importance of morality, responsibility, and obligation toward others. Such excessive introspection cuts man off from both his fellow human beings and from the order of being.

Epitomized by countless individual atoms concerned only or primarily with themselves, the spirit of the present lacks a stable foothold. It does not recognize God and his divine order as instantiated in the natural law, nor is it capable of recognizing that anything of humane importance can be solid, definitive, and objective. On this basis, there is little reason to expect man to begin to reflect deeply on the prospects for his humanity in the face of the mechanization of life, the cult of technology, the proletarianization of urban masses, the growing distance from nature, and the increasing ‘massification’ and uniformity of human life. These are conditions that can only create tyranny—whether communist, National Socialist, or postmodern and relativistic.

If the spirit of the present is mired in atomism and egoism, the restoration of tradition entails a search for the whole, for rootedness. Man can only carry out this search in a spirit of modesty and meekness. He must strive to recognize his limits, the essence of which lies in his mortality. By contrast, the self-satisfied culture in which anything goes, and which “neither knows nor acknowledges limits,” is completely silent on the most mysterious and unavoidable of evils, namely death.

The other aspect of the recovery of tradition, which complements the existential one, is the social dimension of human existence. The individual retains and deepens his humanity by belonging to a community and by experiencing the “co-presence” of another spirit. The autarchic “I” is a mirage; the whole comes before the parts. As the Austrian writer Hugo von Hoffmannsthal argued, what is sought is not freedom but connections—family, regional, historical, cultural, and religious. These ties include a renewed “covenant with nature,” that is, respect for “God in nature and nature in God.” Only on the basis of the restoration of the connection between being and faith, and between being and community, is it possible to renew society and the state.

It is also necessary to pay attention to the Catholic perspective that informs Rieger’s book. Most of the authors in the collection are faithful Catholics: Plinio Corrêa de Oliveira, Walter Hoeres, Reinhold Schneider, Röpke, and Spann. Even in the case Handke, Rieger recognizes a Christian sensitivity. This is why the tenor of the collection reflects a longing for the order of “Christ’s peace” and “Christ’s kingdom,” and indeed for the renewal of Christian civilization.

The decadence of the present is the result of a turning away from the traditional image of God. However, Rieger himself admits that Christianity remains marginalized in Europe. And there has been no religious renewal of late, either before or since 1945. The blame for that partly lies with the institution of the Catholic Church. Particularly after the Second Vatican Council, it made more and more compromises and adapted itself more and more to the spirit of the times.

To many readers, this book may seem fanatical, dangerous, or reactionary, but that would likely not bother Rieger or the men he wrote about. For if the restoration of eternally valid, traditional, and distinctly Christian values—which began to be forgotten during the 15th century, at the latest—is reactionary, then being reactionary is good. The pejorative connotation of the epithet “reactionary” is rather the reflection of the fact that the rationalistic-scientific world, as Röpke wrote, is blind to the eternal laws of society and man. And however much alienation from nature, the natural law, and the Creator is celebrated through the use of various nice-sounding, modern phrases, it will always have catastrophic consequences for the health of the human soul.

Whoever abolishes God will want to abolish hierarchies as well, albeit in vain. Conversely, the enemies of hierarchy will want to abolish God. From the perspective of Rieger and the authors in his collection, hierarchy is a natural necessity. In God’s order, everyone and everything has his or its specific place, task, and dignity. Saints and criminals are equal insofar as they are both equally endowed with intrinsic human dignity, but that does not mean they are equal in every respect.

In response to the objection that the project of restoration outlined by the collection is unfeasible, Rieger and portrayed authors would probably remain unfazed. They would likely remind their critics that the fight for what is eternally valid must be waged even without—and perhaps especially without—the expectation of an earthly reward.