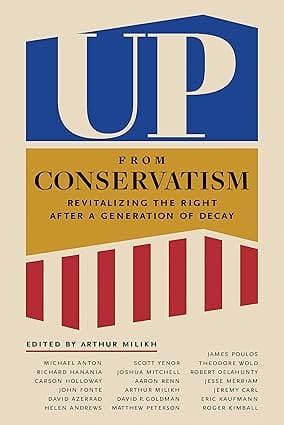

With primary season having already been underway in the United States, June of last year may seem an odd time for Encounter Books to have released Arthur Milikh’s sensational compendium of essays, Up from Conservatism (2023).

Presidential aspirants and their campaign staff were no longer receptive to these kinds of intellectual tomes after launching themselves into the electoral fray. Neither were the voters. Even taking at face value what’s prescribed by his roster of contributors, the conservative lay reader was simply in no headspace to pay much attention to Milikh’s case for “revitalizing the Right after a generation of decay.” They faced the urgency of Trump’s legal troubles, on one hand, and, on the other, with debaters like DeSantis, Vivek, Pence, Christie, and Haley, politically engaged viewers were more consumed by their viral verbal skirmishes than by the nuances of their theoretical dissent.

There’s also a question of resource timing. The American Right may be in dire straits in the overarching culture war, but nine months away from Super Tuesday was hardly a time to reset the foundations of the conservative edifice, even if such a reset were as easy as Milikh suggests. In politics as in life, you run with what you have, and leave the soul-searching for later.

Yet this short-term electioneering is itself precisely an outgrowth of the operational mindset with which Milikh takes issue. Both before and after Trump’s shock victory in 2016, the GOP proved adept at turning its base out to vote every four years, despite being largely dormant in the interim. By the late 2000s, the party’s platform hardly even merited such a well-oiled electoral machine. With the educated urbanites increasingly veering left, the base had turned primarily working-class white, but the party’s agenda had barely budged an inch from 1980s zombie Reaganism. And even after national populism became the party’s dominant faction toward 2016, conservatives proved woefully unable to forge a long-term strategy to dispute the Left’s cultural hegemony, roll back the deep state in both its administrative and national security variants, and raise a new elite from which to staff future administrations. Despite making some progress in this last goal, the other ventures have been abject failures. These failures now risk turning the GOP into an entirely ineffectual apparatus, a vehicle for winning elections with no clear purpose—particularly if a candidate in the mold of Pence or Haley rises to restore the pre-2016 consensus. Milikh’s book seeks to prevent that prospect.

The book runs some scorching diagnostics before offering some radical prescriptions. Milikh is keen to stress that, with the GOP’s aforementioned modus operandi, the Right had overlooked that it could actually lose ground in the culture even as it won at the ballot box— that the economy could remain relatively free even as the judiciary and the administrative state became increasingly tyrannical. After all, the reasoning seems to have gone, since Marxism had been resolutely defeated as a socio-economic regime in the last century, there was no reason to argue against its cultural variant in the new one. ‘Conservatism Inc.,’ as Milikh’s Claremont Institute deridingly calls the modern Right, had burrowed itself into a self-defeating position in which they would “do the economic policy, while the Left governs the culture, controls the moral consensus, and holds the levers of real power.”

To be fair, this is not a failure of the American Right alone. Rather, it is a shortcoming present elsewhere—more forcefully averted in places like Hungary and identified by authors such as Brazil’s Olavo de Carvalho. But more than in Western Europe or Latin America, the American conservative movement has blundered into a fatal error with respect to big business. It thought that, by cutting corporate taxes and deregulating the economy, corporations would be won over against the Left’s statism. But when push came to shove, corporate philanthropies gave anywhere between $100 and $200 billion to BLM-affiliated causes in the wake of George Floyd’s death.

Milikh offered that astonishing figure in an interview on the Kevin Roberts show shortly after the book was published, but his presence on that platform is, ironically, part of the very problem that he hopes to solve. As an alum of the Heritage Foundation (before converting to Claremont in mid-2020), Milikh’s visit made some sense. Roberts was anointed president of Heritage in October 2021, and since then he has swung the organization to the right on several key issues, including immigration and Big Tech. But unlike Claremont (with some notable exceptions), Heritage is more of a lagging follower than a pioneering leader in the Right’s shift towards populist causes. Much of Heritage’s economic platform remains focused on tax cuts, deregulation, and slashing entitlements, to the exclusion of populist concerns related to trade, deindustrialization, and monopolies. On foreign policy, “America’s most influential think- tank” remains wedded to a hawkish worldview that views the territorial integrity of Taiwan and Ukraine as non-negotiable sanctums over which it is worth risking nuclear Armageddon. Ultimately, Heritage’s nods to the New Right conflict with its ambition to retain the largest donor base of any right-wing organization in the country. Part of Milikh’s critique of the modern conservative movement is precisely that it remains subordinate to a donor class that expects good old neoliberalism and foreign interventionism in return for their largesse—and to hell with the base.

Each of the book’s chapters are as minutely researched and argued as they are thematically wide-ranging. They also slay numerous sacred cows, particularly on racial and immigration- related matters. Michael Anton warns that the preponderance of second-generation immigrants in top public and private jobs raises questions of national loyalty. Eric Kaufmann invites accusations of ethnonationalism by claiming that “ethnic majorities are important in anchoring nation- states.” With similar panache, David Azerrad summons the right to “abandon the church of antiracism” and restore the purest form of color-blindness—perceptions of lingering discrimination be damned. Jeremy Carl reaffirms that, contrary to progressive mythology, America is not a nation of immigrants, but of settlers. Ahead of the 250th anniversary of the 1776 revolution in 2026, John Fonte urges the Right to “eradicate” the progressive national narrative entirely, while Carson Holloway pokes holes in the idea of a “propositional nation” founded to achieve intangible aims separate from the particular welfare of its people.

The book is likelier to gain intra-right detractors, however, as it wades into cultural and educational matters. No longer interested in defending the indefensible, Milikh, along with Richard Hanania and Scott Yenor, advocates either destroying the educational establishment or draining it of resources altogether, so that a new one can be built (one assumes they mean the Ivies, too). Helen Andrews argues that female careerism, even when championed by the family- minded Right, does a great disservice to mothers, particularly working-class ones. Joshua Mitchell and Aaron Renn concede, as Protestants, that identity politics soon inserts itself in any weak form of their denominational faith, and that only a stronger form of Protestantism can resolutely defeat it. On economics, David Goldman breaks several libertarian taboos on consumerism, monopolies, deindustrialization, and trade deficits. On the pernicious notion of “rule by experts” that is enforced by the administrative state, Theodore Wold argues against both Chevron deference—which has just been struck down by the Supreme Court—and the Landis premise. Robert Delahunty calls for radical FBI reform to preclude any more politically motivated spying by the agency. And on foreign policy, Michael Anton again puts paid to what little remains of the neocons, observing that China cares more about Taiwan than America does; that deterring Russia’s every interference into its neighbors risks launching us into nuclear Armageddon; and that Mexican cartels are the “gravest danger we face.”

Ultimately, the revolutionary content of Milikh’s blueprint lies in its every policy proposal, but that could already be gleaned from the front cover. In paraphrasing the title of William F. Buckley’s classic Up from Liberalism (1968)—a book that set the tone for the modern conservative movement—Milikh suggests there’s an enemy to be defeated in the quest to reaffirm the quintessentially American notions of ordered liberty and the common good. That enemy dwells in universities, school boards, churches, sports teams, corporations, and the military—but not only in those places. A “cultural civil war” over the contours of the American “regime” is raging across these battlefields, but the New Right has thus far labored under meek and feckless leaders. The long-term rival is the anti-American woke virus, but the more immediate adversary is the establishment old Right, with its perennial attachment to individual liberty and its wish to seek peace with the cultural Marxists. Defeating the Left, as Milikh warns in the introduction, requires overtaking the old Right. Only then will we be able to “correct the trajectory … after several generations of political losses, moral delusions, and intellectual errors.”

His book is an important step in that course correction.

This essay appears in the Summer 2024 edition of The European Conservative, Number 31:102-104.