Photo: © Elisa Haberer, courtesy of l’Opéra national de Paris.

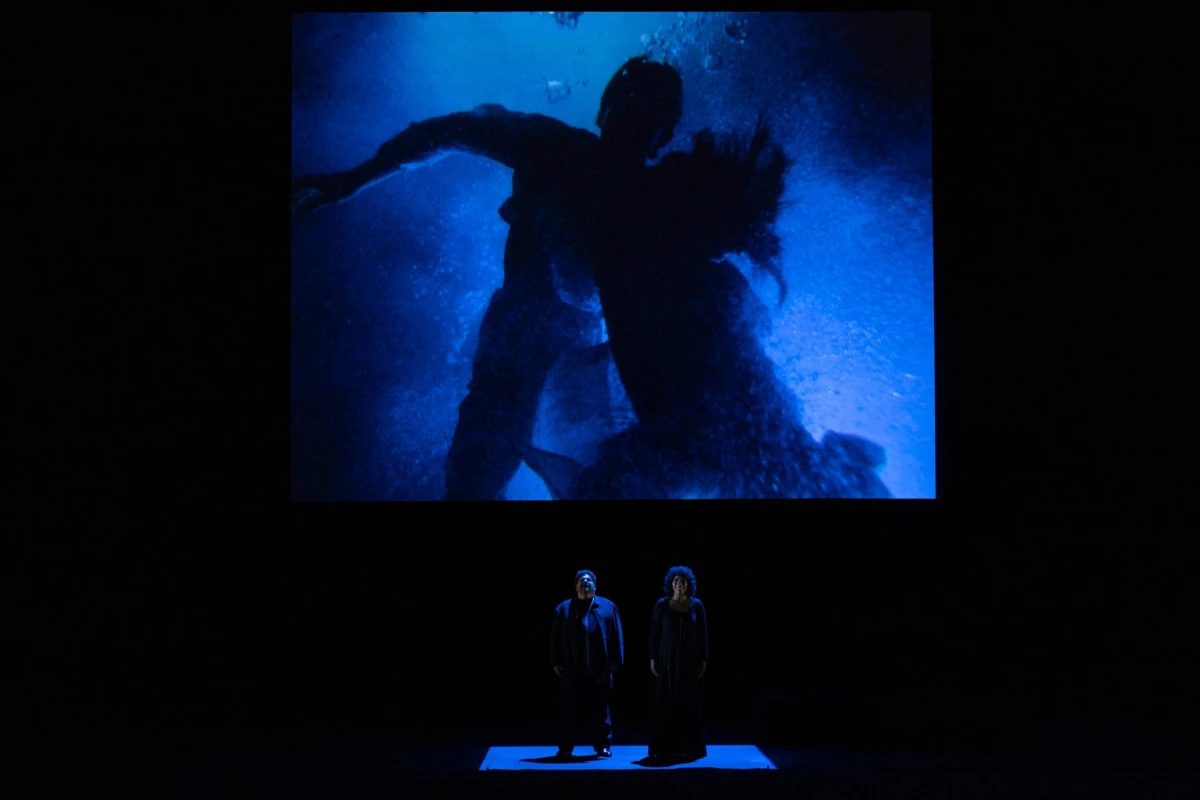

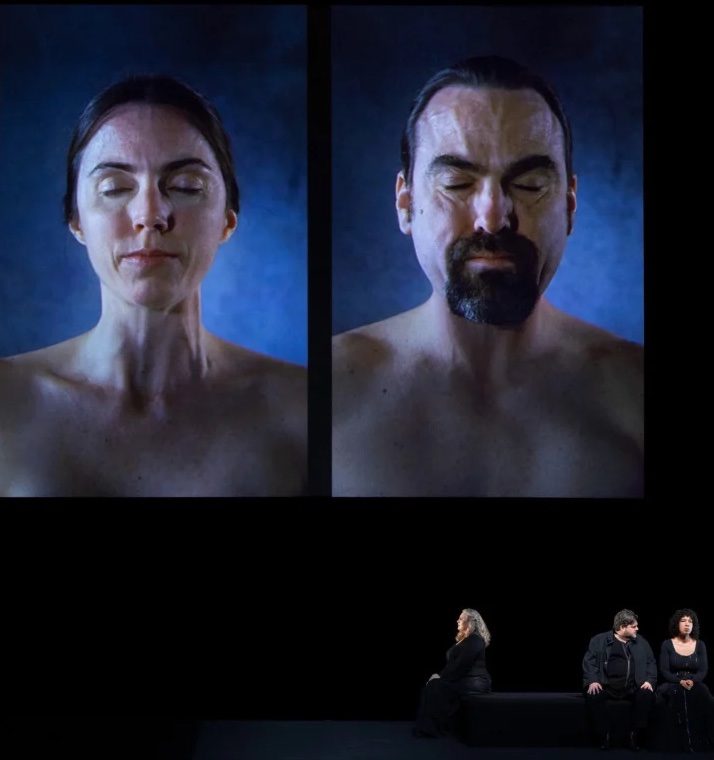

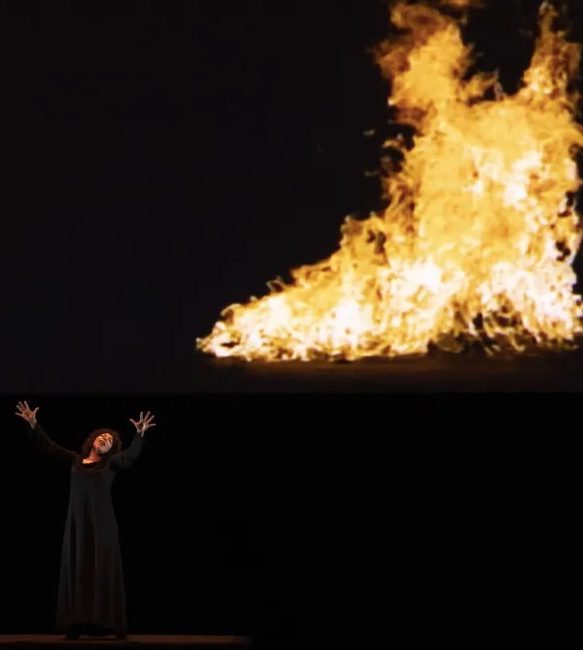

“We’re all very excited tonight,” the legendary provocateur opera director Peter Sellars told me at intermission on opening night of the Paris Opéra’s revival of his storied production of Richard Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde. A feat of striking theatrical innovation when it originated as the “Tristan Project” in Los Angeles in 2004, it relies on massive video installations to reach into the psychological depths that underlie the opera’s surface. Designed and directed by the visual artist Bill Viola, the videos show a parallel set of lovers who mirror the plot’s courtly romance of doomed forbidden love with a spiritual journey in which they are tested by fire and water before being ejected into the air at the moment of Tristan and Isolde’s transcendence.

In the opera, Tristan, a knight of Cornwall, has abducted the Irish princess Isolde who had fallen in love with him despite his having slain her intended, Sir Morold. Tristan’s mission is to take her to his uncle, King Marke, who is to marry her. Waxing wrath, she wants both Tristan and herself to die by poison, but her despairing servant Brangäne instead substitutes a love potion, causing them to amplify their existing attraction. Meeting secretly at night for fear of the daytime demands of Marke’s court, they are betrayed by Tristan’s friend Melot, who acts from envy. Grievously wounded, Tristan withdraws to his homeland across the sea, where he deliriously awaits Isolde. She arrives, but Marke is hot on her heels. Tristan’s servant Kurwenal leads desperate resistance, only to find that Marke has learned the truth and arrived to unite the lovers. Tristan, however, has died of his earlier wounds. In the opera’s famous “Love-Death” (Liebestod) monologue, Isolde can only eulogize him and expound on her reconciliation with loss before she joins him in eternity.

At the time of the Sellars production’s premiere, which was held over three consecutive concerts (one for each act of the opera) before arriving fully staged in Paris in 2005, it was hailed as genius, even if audiences never quite got used to the stage action being so minimal and dramatically overshadowed by the video. Naturally, Tristan’s existential questions and exploration of philosophical depth make the opera a challenge to stage in a dynamic way. Directors have tried all sorts of tricks, lately including what seem like mandatory updates of the setting from medieval times to a constrained 20th-century milieu, and abandonment of physical contact in an attempt to emphasize the characters’ corporeal separation. These efforts are rarely satisfactory, likely because they remind us too greatly of ourselves and our predicaments rather than transporting us to a time and place of legend.

Abstracting the story by layering on another story in video is not much of an improvement, even if the use of video was pioneering at the time of the premiere. But did that innovation lead anywhere? Since 2004, film clips and more sophisticated CGI projections have enhanced stage productions. Usually, they tell a story related to the plot, illustrate action that is referred to but not seen, or offer some sort of interpretive or ironic comment on the opera on stage. I am, however, unaware of any other production that relies on full-length video to relate or augment its plot from start to finish. In this, Sellars’s experiment remains singular and unrepeated, an artistic dead end.

One might appreciate its uniqueness, but the minimal action by the singers still leaves one unfulfilled. They move only slightly under low light beneath the giant video screens, though occasionally, in Paris at least, they sing from the balconies on the sides of the hall. Most costumes are basic black or brown, with only a modern-looking admiral’s uniform for King Marke, who enters through the audience from stage left. Props are nonexistent. Almost comically, the sword that wounds Tristan is Melot’s extended fingers. The projections are unavoidably the center of attention, but technology has advanced in the past two decades and the video now looks dated, like something created in, well, 2004. The production team extols the use of technology in opera, yet it might have considered giving their central product a facelift. The swelling seas on display looked fuzzy and lost focus in panoramic motion. The screens are big, but hardly fill the Opéra Bastille’s vast proscenium. In an age of ever-larger television and cinema screens, increasing the screen size would not have broken the Opéra’s generous budget.

The vocal performance under all the tech was mostly pleasing. The Swedish tenor Michael Weinius appeared in place of the originally announced Gwyn Hughes Jones, who is not much of a heldentenor. Weinius, who began his career as a baritone and preserves that lower timbre, is much closer and gave a muscular performance, even if the treacherous third act monologues suffered from some audible wear and strain. Mary Elizabeth Williams, an American soprano who has resided in Paris since 2002, made her Paris Opéra debut in this performance. The voice is not unattractive, but it sounded thin where it should have bloomed and captured Isolde’s wrathful movements with shrill declamations unsuited for her transcendent scenes. Eric Owens sounded old in the role of King Marke, but King Marke is old so one is tempted to excuse his gravelly vocalizations. He did, however, give a full-bodied account of the wounded monarch’s pain and suffering. Okka von der Damerau’s Brangäne, her Paris Opéra debut, was plush and elegant, suggesting that this artist may have a future as Isolde despite her early work in the mezzo-soprano range. The fine American bass Ryan Speedo Green, another debuting artist here, gave a stentorian Kurwenal.

The Venezuelan-born conductor Gustavo Dudamel has come a long way since his early days as an enfant terrible. His wild hairstyle has been cropped into a more professional look—perhaps an unavoidable consequence of his graying after forty. His conducting, too, was more focused than the unevenness of his early career performances might have caused one to predict. The score of Tristan, an opera that commands what Dudamel claims to be his obsession, radiated brilliantly with a fine Gallic touch from the Opéra’s orchestra.

With extended intermissions presumably necessary to accommodate the video, the evening clocked in at over five hours. That is not unusual for Wagner in more contemplative surroundings than the sparsely functional Bastille, but with the dated imagery the waits were a nuisance and a reminder that the advancing march of technology is not slowing down. The annual Wagner Festival in Bayreuth has announced that its new production of Parsifal will go beyond even CGI to rely on an “augmented reality” system requiring a special headset. After nearly twenty years of Sellars and Viola, it may be time for Paris to consider a fresher approach to Tristan.