Art is a crucial part of any culture. From ancient Egyptian reliefs and Greek pottery to French impressionism and English pastorals, works of art help us to enter into the minds of those who differ from us. At the same time, they enable us to recognize the common human nature that unites all peoples.

Some of the most striking examples of this are when elements from different cultures and times are melded together in a single work. Think of how Virgil’s Aeneid is so distinctively Roman while being profoundly indebted to the Greeks, or of how the formation of Romanticism was bound up with the ruins of earlier epochs, or of how J.R.R. Tolkien’s distinctively English mythology was inspired by the myths of earlier civilizations.

One contemporary graphic novelist whose work exemplifies this kind of cross-cultural pollination is Gene Luen Yang. Born in California to Asian-immigrant parents, Yang was raised in the Catholic faith. After discovering comic books as a child, the young boy soon began writing and drawing his own. In time, this boyhood passion would flourish into a career, and he is now one of the best-known contemporary cartoonists, writing and illustrating his own original graphic novels and penning scripts for DC’s Superman and Monkey King and Marvel’s Shang-Chi. In addition, his works have achieved critical success, with two of his works earning Prinz Awards. He is even the third graphic novelist ever to be given the prestigious MacArthur ‘Genius Grant’ Fellowship.

This success has led to ample discussion of Yang’s works. Much of this discussion has focused on how Yang expertly depicts the interplay (and, at times, the clash) between Eastern and Western cultures within the context of deeply human stories. However, far less ink has been spilled over the role that Christianity has in this interplay.

It would be far too much to attempt to discuss all of Yang’s work, so today we will focus on three works published by First Second Books, American Born Chinese (2006), Boxers and Saints (2013), and Dragon Hoops (2020). Over the course of these three works, readers encounter gods and goddesses, tales of the Boxer Rebellion, and contemporary American high schools. These graphic novels are exciting, entertaining, and accessible, but they also wrestle with the ways that Western ways of life, Eastern culture, and faith come together and break apart.

American Born Chinese

Yang’s first mainstream work, American Born Chinese, alternates between chapters of three stories that initially appear completely distinct but become unified as they go on. The first tale begins strikingly with an image of gods, goddesses, demons, and spirits schmoozing at a dinner party. This is the reader’s first introduction to Yang’s art style. Each face is quite simple. Faces in the background look nearly identical, while any characters we are meant to notice have features (noses, eyes, hair, head shape, etc.) that immediately distinguish them from the others. The coloring (by Lark Pien) is pitch-perfect, simple and undistracting, naturally complementing Yang’s own style.

On the next page, the first of the book’s three protagonists appear, the Monkey King of Flower-Fruit Mountain. This king (a play on the protagonist of the classic of Chinese literature, Journey to the West) is a god who rules over the other monkeys on his mountain. He is a mystical master of kung-fu, even being able to summon a cloud on which to travel. His heightened senses alert the Monkey King of the gods’ party, so he flies to heaven on his cloud steed. Once there, he must wait in a seemingly interminable line to enter, but when he finally makes it to the door, he is turned away because he is not wearing shoes. A great fight breaks out, and the Monkey King returns to his mountain, brooding, for the first time, over the ways in which he is unlike the other gods.

The second (and initially most realistic) plotline is about a young American-born Chinese boy named Jin Wang. Despite being introduced second, Jin is arguably the protagonist of the graphic novel. Raised for the first few years of his life amongst other Asian-American children, in third grade he moves to a new school that is almost exclusively white. Jin has little in common with the other students and is initially bullied. He learns to fit in, however, and when another Asian student transfers to the school, he teaches him how to avoid being seen as weird. Jin’s plotline is the most immediately ‘relatable,’ given how universal the experience of being an outsider is.

The last—and most surreal—plotline is called “Everyone Ruvs Chin-Kee.” This part of the story imitates the classic American situational television comedy, or ‘sitcom.’ It is centered on Danny, the all-American teenager, whose cousin “Chin-Kee” (a play on the racist epithet ‘chink’) is coming to visit. Chin-Kee is the incarnation of every stereotype about Chinese people turned up to an impossible degree. In addition to being drawn in the style of early 20th century caricatures of ‘Chinamen,’ Chin-Kee is constantly mispronouncing Rs and Ls, his food looks like living garbage, and he openly talks about wanting to bind the feet of beautiful American (or “Amelican”) women he meets. All this is played for laughs, but at the same time we see how it horrifies Danny and his classmates.

While these three plotlines may sound disconnected, the experience of reading them is not. Each one brings readers into a fish-out-of-water story, and they all deal with themes of self-knowledge, self-acceptance, and integration into the larger order of reality. The first two of these themes are perhaps unsurprising in a story that focuses on a second-generation immigrant, and they have been widely-discussed. What has not been considered as often is the third theme, that of fitting into a larger order of reality. Despite the intimacy of the stories being told, American Born Chinese has a grand, even cosmic, scale. I don’t want to spoil anything here, but the Monkey God’s tale is not limited to interacting with pagan gods, for Tze-Yo-Tzuh (literally “He Who Is,” obviously meant to be the Judaeo-Christian God) plays a crucial role in his story.

Just as the Monkey King can only understand himself in the context of Tze-Yo-Tzuh and the whole order of His creation, so Jin must grapple with his place in reality. Yang’s story is not a shallow tale of racial diversity, but instead takes the weight of heritage and culture seriously. Jin is between two worlds, formed in many ways by his Chinese heritage but wanting to be a part of American culture. In an early scene in his story, the young Jin is asked by an old Chinese woman what he wants to be when he grows up. He responds that he was to be a “Transformer,” a robot that can turn into a car, the stars of his favorite cartoon. He explains that his mother thinks this idea is foolish, and that little boys do not grow up to be Transformers. The old woman, however, tells him that “It’s easy to become anything you wish, so long as you’re willing to forfeit your soul.”

Whether or not Jin forfeits his soul is the story of the rest of the graphic novel, and it’s a story well worth reading.

Boxers and Saints

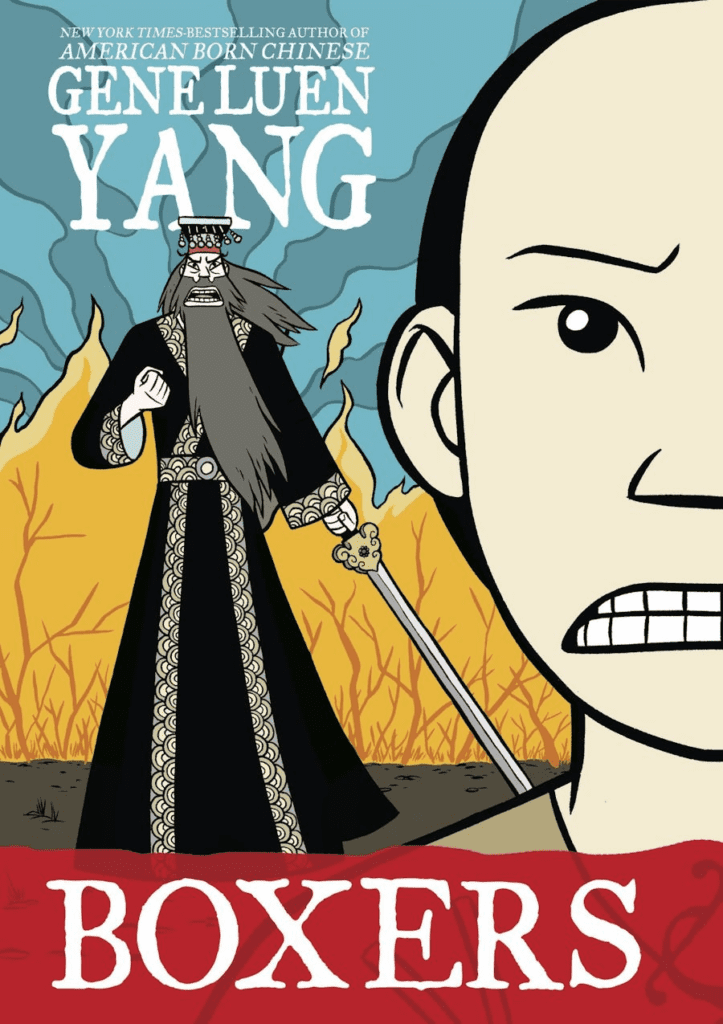

Gene Luen Yang’s most powerful work, in my opinion, is Boxers and Saints. More precisely, it is a two volume work, one entitled Boxers and the other Saints. The first is focused on the Boxer Rebellion, a violent uprising of Chinese people who believed Western influences were corrupting their great and powerful nation. The second volume, in contrast, focuses on the Chinese people who embraced the ‘Western’ religion of Christianity, often suffering and even being martyred in the rebellion. Each volume pulls readers completely into the mind of its protagonist, showing unflinchingly the good and bad of both traditional Chinese society and ‘Westernized’ Chinese Christian culture.

The first volume, Boxers, focuses on Lee Bao (initially called “Little Bao”), a boy living in a peaceful Chinese village. He loves the springtime festivals in his village, where dramas are performed, games are played, and the idol of Tu Di Gong, the local god of the earth, is venerated. Readers are brought into this world and can see its beauty and order. At the same time, Yang is honest about the abuses that occur. Early in the work, a man attempts to swindle an old woman and eventually begins beating her. It is only thanks to Little Bao’s father that the brute is stopped. Little Bao idolizes his father: for him, he incarnates all the virtues of Chinese civilization.

Soon, though, the beastly man finds a group of Christians and cynically pretends to convert. He returns to the village with protection and a Catholic priest. Despite his good intentions, the priest’s understanding of the Chinese language and customs are rudimentary to say the least, and in trusting the man he ends up making the situation of the honest villagers (including Bao’s father) worse. The priest also destroys the idol in hopes of bringing the villagers to Christ. Things soon escalate, and Bao is left to grow up in a village that is a shadow of its former self. Once he is older, Bao ultimately joins the Society of the Righteous and Harmonious Fist, the group that will later lead the Boxer Rebellion.

The other volume, Saints, focuses on the daughter of a woman who had already lost all three of her previous children. The daughter is never given a real name. Instead, she is simply named “Four-Girl,” being the fourth child and born on the fourth day of the fourth month. (“Four,” in their language, is also a synonym of “death.”) While cleaning, she accidentally breaks her family’s idol, and she is called a “devil.” As a result, she begins to see herself as something of a devil, lacking in any goodness. However, in time she becomes Catholic. (The story of how this happens is both touching and hilarious.) Her life is ultimately transformed due both to her mystical visions of St. Joan of Arc and the Boxer Rebellion.

It is hard to communicate how masterfully Boxers and Saints captivates the reader. Despite my appreciation for Yang’s work, I dragged my feet on reading this work until this year, because a 500-page comic about the Boxer Rebellion sounded only slightly more appealing than watching paint dry. However, once I picked it up, I was loath to put it down. Each story is profoundly compelling, and it forces readers to grapple with how—or perhaps whether—East and West can live together harmoniously. Additionally, it is one of the best confrontations of the tensions between nationalism and Christianity I have ever read. The art is some of Yang’s best, retaining his cartoony style while being more detailed than his previous work.

But what is most powerful about the book is how it gives the Boxers and the Christians each their due. As a conservative concerned about the effects mass immigration has on the West, I could immediately sympathize with Bao. But as a Christian, I also immediately sympathized with the Christians in the story. As I came closer to the end, I wondered how Yang could possibly square the circle and close the work in a way that felt true to everything that came before. I’ll just say that he does. Finishing the closing pages of this work was (if I’m not mistaken) the only time that reading a comic has ever made me cry.

Dragon Hoops

After the historical, East-West drama of Boxers and Saints, Yang’s next solo work, Dragon Hoops, might sound like a step down. It is a work of nonfiction, telling the story of a very competitive high-school basketball team that is trying to win the California state championship. It is also the only of the three works to be devoid of the magical realism for which Yang is renowned. This might therefore sound like a very small story, but Yang’s strength as a storyteller and knack for getting into the minds of his characters make it feel like the biggest story he has told thus far.

Dragon Hoops is told in the first person, with the comic version of Gene Yang occupying the role of both character and storyteller. He opens with the admission that he never found basketball (or any sports, for that matter) of any interest to him. Clips of triumphant sports stars lacked the inspiring feeling that superhero comics gave. Yang introduces the reader to the school where he teaches, Bishop O’Dowd, a Catholic high school in Oakland, California. Its basketball team is renowned, but Yang had never taken any interest in the sport. Yet one day, after a sleepless night trying to come up with a subject for his next graphic novel, he decides to approach Coach Lou, a step that will turn out to be consequential, not just for his next graphic novel, but for his entire life.

The story follows the Bishop O’Dowd Dragons throughout the season, but it isn’t primarily about the action of the games themselves. Instead, Yang introduces readers to individual players. When you first meet them, they seem like a typical bunch of high school basketball players. Soon, however, readers come to know and care about players as characters—as human beings. They come from different ethnic backgrounds, socioeconomic classes, and religions, and Yang takes the time to let you into their worlds. This personal touch is complemented by the way that Yang integrates the history and strategy of basketball into the story. These explanations never feel out of place, and they allow readers to understand and consider the main story more deeply.

Though it deals with a number of tensions that follow from the team’s diversity, Dragon Hoops is, in some ways, the book in which Yang’s examination of cultural interplay and cultural clash most clearly resolves in cultural harmony. This is made possible by the fact that the players are teammates. Some students face tough battles off the court (and one is sneered at on the court because of his race). But when they come together, they are a team, unified for a single goal.

Catholicism (and religious faith more generally) has more of a background role in Dragon Hoops than in Boxers and Saints—though one of the most interesting historical interludes has to do with why American Catholic schools are so good at basketball. Bishop O’Dowd is a Catholic school, but many of the players are not Catholic. This sometimes leads to cultural disconnects. However, Coach Lou brings the students together before each game to pray. All the players, Catholic, Protestant, Sikh, and otherwise, are unified before God.

Unity in diversity

This theme of unity before God is, I think, a key point to thinking about all of Gene Luen Yang’s work. Some conservative readers might be inclined to write off his books without reading them because they are seemingly so focused on ‘diversity.’ I myself find that many works that focus on diversity for its own sake are rather bland and uninteresting. However, as indicated at the beginning of this article, there are many works of art wherein the interplay of different cultures and modes of life allow something powerful and new to emerge. Yang’s graphic novels are a contemporary example of this.

Fundamentally, the question of cultural interplay in art is not one of diversity, but of unity. Take a thousand pieces of multicolored glass and throw them randomly and you have a mess, but in the hands of a master you have a mosaic. This is true also in political life. If a country is nothing more than tribes competing for dominance, then you have a Thucydidean civil war or a Hobbesian war of all against all. But when people and communities bring their distinctive gifts together in support of the common good, there you have the promise of earthly peace and happiness.

This peace is difficult to maintain, and in a fallen world it will never last. This is why it is in need of the unity of the God who is Three-in-One. Yang’s willingness to allow his Catholicism to influence his art is, I think, part of what makes his work so interesting and so valuable. He does not simplify the complexity that comes from diversity and cultural melding. It is not always easy for a young American-born Chinese boy to get through middle school. Nor was it easy for Chinese culture to integrate Western elements in the time of the Boxers. Nor is it always easy for a basketball team to have members with seemingly little in common. But at the same time, Yang’s works seem to teach us that it may be possible to live together, under God. It is not easy, or simple, but it is something we can do, not just for our good, but for the good of our communities, our nations, and our world.