In such turbulent times as ours, there is nothing we need more than true models of holiness to remind us of the essential values of a life lived in accordance with the graces we have received through the sacrament of Holy Baptism. The Habsburg Way, a recent book by Archduke Eduard Habsburg, is an anthology of such models of virtue. The values it proposes for reflection and realization are those inherent in Christian spouses. And the stakes are emphasized from the very beginning by the author:

This book is intended to demonstrate how a set of values can be implemented into our lives and times today. I will show how the Habsburg family continues to embody the same ancient values even into the twenty-first century, long after the Austro-Hungarian monarchy ended.

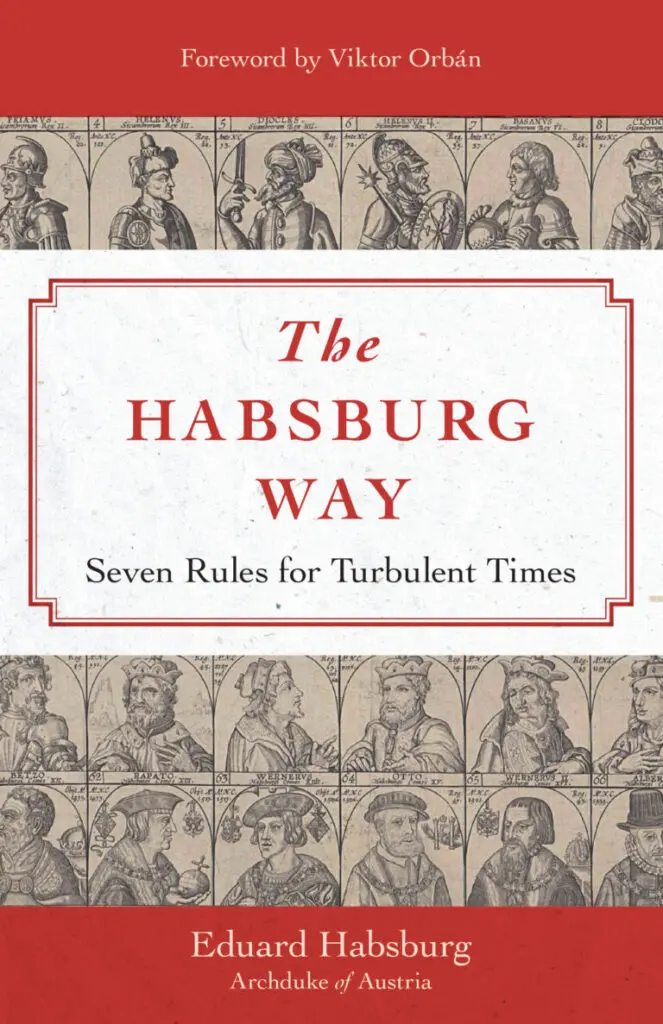

It is significant that a political leader like Hungarian Prime Minister Viktor Orbán has written the introduction to the book. Regardless of whether we are democrats or embrace traditional convictions such as those of Catholic royalists, we all must appreciate the message conveyed through such a gesture. For this is about the recognition of universal values, transcending our personal political choices. Ultimately, it concerns the lives of people everywhere and the fundamental values that shape them: family, motherhood and fatherhood, and education for a virtuous life. In these essential points, systematically attacked and distorted today, a member of a royal house with an exceptional historical role meets in his mission with a professional politician of European democratic life. Although rather unexpected, this is remarkable.

A particular sentence from Prime Minister Orbán’s introduction caught my attention: “We affirm that mankind can best find happiness in the family.” The statement is perfectly congruent with one of the significant teachings you will find in the texts of Saint Thomas Aquinas. Discussing the ultimate purpose of human life, happiness, he shows that there are two kinds of happiness. The first, perfect, is that of the saints in Paradise. According to Christian belief, this perfect happiness can only be attained after death, in the ‘afterlife.’ The other form of happiness, imperfect like everything earthly and therefore transient, is accessible to all people here during our fleeting lives. And this imperfect happiness depends on friendship.

At this point, Saint Thomas, despite being a monk (and therefore celibate), emphasizes the extraordinary value of the family based on the harmonious, friendly relationship between spouses united by an indissoluble marital bond:

There seems to be the greatest friendship between husband and wife, for they are united not only in the act of fleshly union, which produces a certain gentle association even among beasts, but also in the partnership of the whole range of domestic activity. Consequently, as an indication of this, man must even ‘leave his father and mother’ for the sake of his wife, as is said in Genesis (2:24). Therefore, it is fitting for matrimony to be completely indissoluble.

Summa contra Gentiles, III.2, 123.6

Archduke Eduard’s book is, above all else, a confirmation of such Christian teaching about the foundations of Christian marriage. The background of the canvas, on which the author paints this extraordinary work before our eyes, is most fitting: joy. This background is expressed in a single confessional sentence: “For me, marriage is not simply a fundamental building block of society; it has been one of the greatest sources of joy.” Then, with this background that so spontaneously encapsulates the ultimate goal of Christian life and of our very creation by God—happiness—he describes the requirements for those who have or wish to have a joy-filled marriage:

Shared faith, a mutual understanding of the sacredness and indissolubility of marriage, a common belief in the importance of family and the openness to children, similar societal background and perspective on social responsibilities—and, ideally, a similar sense of humor and interests.

I know of no clearer, simpler, and more comprehensive description of the key elements of a happy marriage. Personally, I would recommend it for meditation to any young man or woman seeking their ‘better half.’ If the subject of the book, therefore, is Christian marriage, the ‘material’ from which it is woven in its content is the numerous family stories skillfully recounted by the author. Its content is a gallery of notable members of the Habsburg family, and Archduke Eduard introduces them throughout the 158 pages of his book:

I hope that, by the end, you will have gotten to know a number of very different members of my family, including: the hooked-nosed Rudolf, who in 1273 became the first Holy Roman Emperor; The Last Knight Maximilian, who lived an anachronistic life of courtly romance in the fifteenth century; the devout Archduchess Magdalena, who founded a convent in the sixteenth century; the towering Mother of her People, Empress Maria Theresia, who bore sixteen children over two decades during the eighteenth century; and the soft-spoken giant of faith, Bl. Emperor Karl, who lived during the twentieth century.

But do not think that only the good and virtuous are presented. Just as in a Charles Dickens novel, far from being a self-flattering presentation of the remarkable House of Habsburg, the book contains negative examples, like that of the Holy Roman Emperor, Joseph II (1741–1790). If Socrates was the one who taught us that those leaders who can do the greatest good can also do the greatest evil, this example confirms the truth of Socratic assertions through the magnitude of his disastrous anti-Catholic policies. For only a great and terrible emperor could almost completely eliminate contemplative and monastic life from his kingdom.

Providing clear historical details, Archduke Eduard shows that on 12 January 1782, Joseph II signed a Decree of the Dissolution of Religious Orders. Thereby, in just one year, one hundred forty contemplative houses were closed. This was done because of their ‘uselessness’—for what use can prayer, and only prayer, have for those animated by a ‘pragmatic’ (i.e., ‘political’) vision? Even the emperor’s lack of respect for ecclesiastical authority is described—reluctantly, perhaps—but with complete honesty by the author, who also recounts Pope Pius VI’s visit. The description speaks for itself:

In 1782, Pope Pius VI made a fruitless journey to Vienna to discuss the matter with the emperor. When the Pope departed, Joseph courteously accompanied him to the monastery of Maria Brunn, gave him a goodbye present—and then immediately shut down that very monastery the moment the Pope was out of sight.

Pursuing historical accuracy to the end, His Excellency reveals that, in 1760, Empress Maria Theresa had begun to close monasteries in Austrian Lombardy. As I mentioned, all historical deeds—eliminating certain holidays from the calendar, introducing civil marriage, etc.—are presented to us with complete honesty. Moreover, these are qualified, as they should be, as “grievous.” At the same time, however, unlike the ‘revisionist’ historians, who are always eager to condemn the past and its representatives without any nuance, Archduke Eduard offers a model of prudence in judging predecessors:

I do want to be careful about passing judgment on Joseph II’s personal faith. He may have been devout in his own fashion: he went to Mass and to Confession—and at least he never seems to have been a Freemason, despite having been surrounded by Masonic advisors and having implemented many Masonic ideas. In fact, he referred to Freemasonry as ‘a charlatanry.’

At the same time, however, after weighing the positive and negative elements, both personal and related to his policies, he does not hesitate to issue a negative verdict when the facts are clear and indisputable:

But whatever his personal beliefs, the destructive consequences of Joseph’s legacy with respect to the broader Church, faith, and religious communities is an undisputed part of the historical record.

If I have given a relatively large space to the presentation of a negative character from the House of Habsburg, this has a demonstrative intention: I want to show skeptics what a true model of transparency and honesty means in evaluating history. On the other hand, readers can understand that they will not be reading a beautiful book on the ‘lives of the saints.’ In fact, it is a first-hand history book. Even though it provides valuable bibliographic recommendations for those history enthusiasts (like myself) who want to have the broadest knowledge of history and the House of Habsburg, Archduke Eduard’s book is, ultimately, a book based on the testimonies of those who lived through what we, ‘ordinary people,’ read and learn from history textbooks.

In the spirit of the author, I now turn my attention to the luminous personalities presented—the positive characters of the Habsburg story. And I can assure you, this collection is much richer than the negative characters. Moreover, the author informs us from the very beginning that his goal “is not to list as many negative points as positive in order to give the impression of being ‘balanced.’” Because, as His Excellency tells us, the book is “a love letter to my family.”

One aspect that attracted me to this reading is its serene and encouraging tone, without falling into the trap of facile optimism, throughout the entire narrative. This is another example of something that, in the era of pessimism, cynicism, and lamentations, we greatly need. What is the secret of this state of mind? It is the one common to all those situated in that place that Holy Providence, in its eternal wisdom, has reserved for them. Also, identifying the battlefield (postmodern culture) and the adversaries (immorality and all hostile currents against family and life) are other necessary ingredients for a general who does not want to fight in vain.

Certainly, I could choose numerous fascinating examples of Habsburgs who have risen to the occasion. However, among all of them, no one is closer to me than that emperor and king whose name I gave to the sixth son born in our family, Charles, and his wonderful wife, Empress Zita. We learn from the very beginning that they had an exceptionally unique marriage, similar to that of the Saints Louis Martin and Marie-Azélie Guérin, the parents of Saint Thérèse of Lisieux:

I think that the Habsburg maxim in favor of marriage may have found its purest realization in this surprisingly humble couple.

And the fruits were abundant, despite the very short life of Blessed Charles I of Austria (he died at only 34 years old):

Their union was blessed with eight children before Karl’s untimely death in Madeira in 1922. (Their last child was actually born after he died.) Those children appeared in public regularly with their parents, and the whole Austro-Hungarian Empire had an example of what a family should be: a man and a woman, faithful to each other, and obviously in love.

Over the past ten years, I have looked at as many photos of the royal couple as I could find. Their joy in being together has always delighted me. The love they had for each other is, in these century-old images, clearly visible. Often, their faces shine. With a little imagination, you can see in them those happy princes and princesses from the stories of Hans Christian Andersen, Petre Ispirescu, or Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm. Their fidelity was accompanied by a friendship that only spouses—as Saint Thomas Aquinas teaches us—can have for each other. But can there be light in this world without darkness?

The preserved photos from the exile period in Madeira are disturbing. His Majesty’s face is marked by the suffering that belongs to those who are denied any place in this world. We read in his expression all the bitterness that a person can feel when denied the right to exercise the vocation for which he was created by God. The burden that weighed on King Charles resembles that which the Savior Jesus Christ carried. For if the divine King and Savior had the right to existence in this world denied through crucifixion, the same right was denied to King Charles through exile.

We can easily deduce that, through his suffering, the last Catholic emperor of the remnants of the Holy Roman Empire became one with Christ. At the same time, his wife’s behavior shows what a woman committed to the path of virtue can achieve. Empress Zita’s face in the photos from the exile period perfectly reflects the purpose for which God created woman: to be ”a help” to her husband (Gen. 2:18). You see no hesitation in taking up this cross, almost as terrible as her husband’s. The empress has a calm face, despite the enormous pressure she must have felt. Widowed, she shows nothing of the hidden suffering in her heart. She has a dignified, serious, and grave expression that reflects only the immense responsibility of being a mother to her children. If you read a monograph like Zita impératrice courage by Jean Sévilla, you will learn how this extraordinary woman lived and thought. I sincerely hope that the grace of God will work in such a way that ever more women who truly want to be Catholic will wholeheartedly follow her example.

I like to believe that Archduke Eduard will agree with me in my assertion that the most expressive photograph is that of Empress Zita at the age of 95. Surrounded by the entire family, seated right in the center, small and dressed in black, she is like the tiny mustard seed from which an impressive tree has grown. For all the generations of her descendants surrounding her represent the rich branches of this family tree. What better lesson could we receive today, when so many people deprive their lives of this irreplaceable vital wealth—children?

If, aided by the book of His Excellency, we delve into the core of the lives of these holy members of the illustrious Habsburg family by participating—as much as possible through reading—in their joys and sorrows, it is natural to ask ourselves: What is the secret of a happy life and marriage? The answer is found in Archduke Eduard quoting a memorable sentence from Emperor Charles:

If one didn’t have prayer or the devotion to the Sacred Heart, all of this would not be tolerable.

Indeed, prayer—through which we knock at the gate of the Sacred Heart of our King and Savior, Jesus Christ—is the main means that can help us navigate through the troubled ocean of this fallen world. What else remains when, as happened to the Catholic bishops in Romania who were all imprisoned by the communists, you have nothing left—not even access to the Holy Liturgy? The words of Blessed Charles faithfully echo the teachings of Saint Alphonsus Maria de Liguori, who emphasized that those who do not pray cannot obtain salvation. This is why I believe that this is the first and most important lesson that the archduke’s book conveys to us.

If the virtue of religion is everything that is most important for our lives, prayer is the essence of the virtue of religion. All else, including participation in the Holy Liturgy, depends on embracing this axiom. And the family, as well as bearing the crosses of each of its members, depends entirely on the insistence with which we, in prayer, call upon the only One who can truly help us: God. For the recapitulation of such an essential and ever-timely lesson, we must thank Archduke Eduard of Habsburg for the gift of his unexpected and wonderful book.