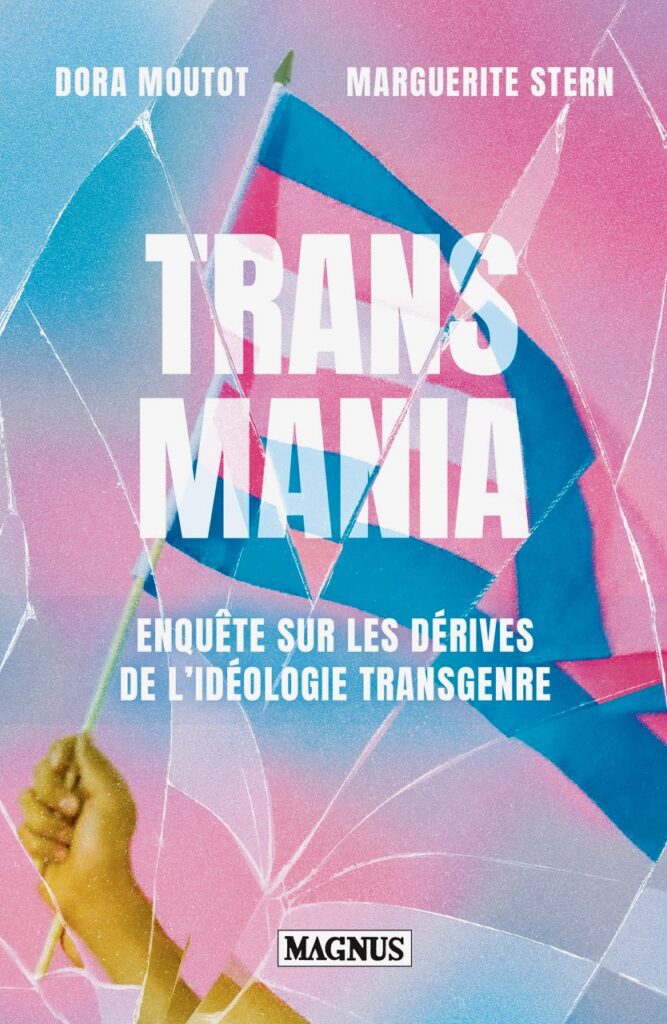

The publication of this pink-and-blue book was like a bombshell in France: two women, Dora Moutot and Marguerite Stern, who come from militant leftist feminism, chose to cross the Rubicon and tackle the evils of transgender ideology in all its forms. It was a daring and more than courageous gamble. Courageous, because today, the ideology of transgenderism—for it is indeed one, as the authors set out to demonstrate with conviction—exerts a terror on the mind worthy of Stalinism in its heyday, minus the physical killings. But in the age of social networking and e-reputation, there are symbolic killings that can be extremely violent.

This essay is the fruit of a long road to Damascus for two women who were never predestined to cross over to the ‘dark side’ of the force. Marguerite Stern is a former FEMEN activist, and not so long ago, she was showing off her bare breasts in Notre Dame de Paris. Dora Moutot is the former deputy editor-in-chief of Konbini, a trendy online medium concentrating on what a politically correct way of life should be.

Both convinced and committed feminists, they took the road of conversion when they realised that, in the name of transsexual rights, they were no longer allowed to defend this sympathetic and disappearing population: women. Singled out and stigmatised as TERFs (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminists), like J.K. Rowling and so many others, because they refused to accept that a man force-fed hormones and surgery could become a woman, they set out to trace the thread of this Soviet-style madness that would have us see black where we see white (or vice versa).

The result of this fascinating investigation is almost 400 pages long.

The book is not a pamphlet or an easy, vindictive rant, but an in-depth study—with all due respect to those who attack it, and who generally haven’t bothered to open it. As an academic, I was even pleased to find a respectable number of footnotes, without which no book could claim to be ‘serious.’

As a red thread running through their demonstration, Moutot and Stern invite us to follow, with a certain amount of humour, the tragicomic journey of Robert, who chose one day to become Catherine—a fictional figure who gives a concrete face to the delusions of transgenderism. This humorous counterpoint is useful for adding a little levity to a gripping read about a terrifying reality.

Methodically, they go into successive depths on the mechanisms of transgender ideology.

The first part looks at the process of transition or ‘sexual reassignment’ and its logic. With rare patience and pedagogy, Stern and Moutot explain what can lead a married man with a family to believe that he is a woman: the byways he takes, through addictions and personal cracks; the time spent on social media and the messages of enrolment they deliver; the underlying psychiatric problems—for there are many of them.

We can sometimes get lost in the subtleties of the matter: is a transfeminine man, i.e., a man who has become a woman, who loves men but is trying to become a woman, still a homosexual? But can a transfeminine man, i.e., a man who has become a woman, who loves women but is trying to become a woman, be considered a lesbian? I’m sure you had never suspected the existence of such dilemmas.

Confucius maintained that “we must correct our denominations.” “The perversion of the city begins with the fraud of words,” added Plato. We will be grateful to Stern and Moutot for their constant efforts to combat the fraud of language. It is this passion for reality, against all odds, that has led to them being targeted by trans activists—who, in the pursuit of their vindictiveness, are definitely proving the truth of what the authors say: the existence of a new thought police force tracking down gender crimes. No, a man who tries to become a woman never becomes a woman. Stern and Moutot defend the expressions ‘transfeminine man’ or ‘transmasculine woman’, which have the merit of knowing who or what they are talking about.

The accusation of ‘transphobia’ is thrown in their faces all day long. They are greeted with leaflets and tags hammering out ready-made slogans like ‘transphobia kills’. But the touching pages in which the authors recount their encounters with trans people who have been wounded by life are full of a deep compassion that prevents them from being seen as hateful people.

The reader learns a great many fascinating things in this dense essay, which challenges the preconceived ideas that are peddled by conventional wisdom. We discover, for example, that far more women make the transition than the other way around. They reject and despise their female bodies, proof of the terrible malaise of our supposedly liberated society with regard to true femininity. We learn that puberty blockers don’t block anything at all, but rather destroy an in-growth body, because biologically, hormones control much more than just the sexual organs in the human body.

After reading these dense, hard-hitting chapters, you’ll want to compile a little vademecum of irrefutable arguments to be brandished at dinner parties—and there are plenty of them.

Taking hormones will never turn a male-born athlete into a woman: independently of our hormones, more than 3,000 genes contribute to the difference in musculature between the sexes.

‘Gender dysphoria’ is not just a matter of hormone treatment. 75% of children who undergo a sexual transition suffer serious psychological problems.

In France, the cost of a transition for a man trying to become a woman is almost €120,000, entirely covered by the public purse under the heading of ‘long-term illnesses’. But describing transgenderism as an illness can lead you to the court. And so on.

The second part sets out to describe what the authors call the transgender ‘crusade’: an all-out assault on education, medicine, marketing, and laws. There is almost nothing to stop it. The obsession with the danger of transphobia, brandished like a banner, would almost make racism seem an authorised opinion today. ‘Transmania’ is an international enterprise with powerful relays, and a major role is played by the United States in this great game of perversion of reality. The good souls can cry conspiracy: nothing that Stern and Moutot put forward is not justified; everything is sourced and supported.

The third part—and you’ll appreciate how the stakes have been progressively raised—asks the fundamental question, the answer to which cannot yet be definitive: why? Why has transgender ideology become so pervasive in our societies that it exerts a form of mental terror on individuals, who feel obliged to acquiesce to a powerfully altered version of reality?

The answer is manifold. It has to do with a demiurgic philosophy that predates transgender madness by many years—the eternal temptation of the creature wishing to replace the creator and shape life to its own liking. Powerful commercial, pharmaceutical, and political lobbies obviously have an interest in this. They alone can’t explain the movement. The authors of this book draw up a convincing outline of the horizon of transgenderism, i.e., transhumanism. It responds to the same temptation to recreate reality in order to free it from material vicissitudes—to the point of imagining beings who could become pure spirits and will use computers to put an end to their necessarily limited corporeal existence. In the end, we’re not far from a form of technological Catharism whose ultimate fulfilment will come when man and woman, creatures of God and his infinite love, cease to exist. The religious argument is absent from the reflection—it was not the purpose of the essay—but the doors are opened by the authors with sufficient finesse to allow it to slip through.

The revelations contained in the book may not be entirely unfamiliar to readers of The European Conservative, which has been tackling the subject of transitions and detransitions for many months now in its columns, following the scandal at the Tavistock clinic, and drawing up an updated inventory of policies on puberty blockers in Europe. But they have the merit of being brought together in one place, in a way that is both precise, detailed, and accessible to the average person. It is particularly recommended reading for parents so that they can detect, before it’s too late, the signs of recruitment to which their children may be subjected via social media such as TikTok or Discord, which recruit new young victims relentlessly.

Since its release, a manner of censorship has been unleashed in France to make the book inaccessible. Booksellers hide it, try to place it at the top of the shelves, or simply refuse to order it. The mayor of Paris banned posters promoting it from the streets. But there are days when Amazon, fortunately, or—even better—ordering directly from the publisher, can get around the pitfalls. As a result, the book is rocketing to the top of the sales charts, despite more or less discrete attempts at social auto-da-fé.

All that’s missing now is an English-language publisher to bring the fruit of Dora Moutot and Marguerite Stern’s salutary work to a wider audience.