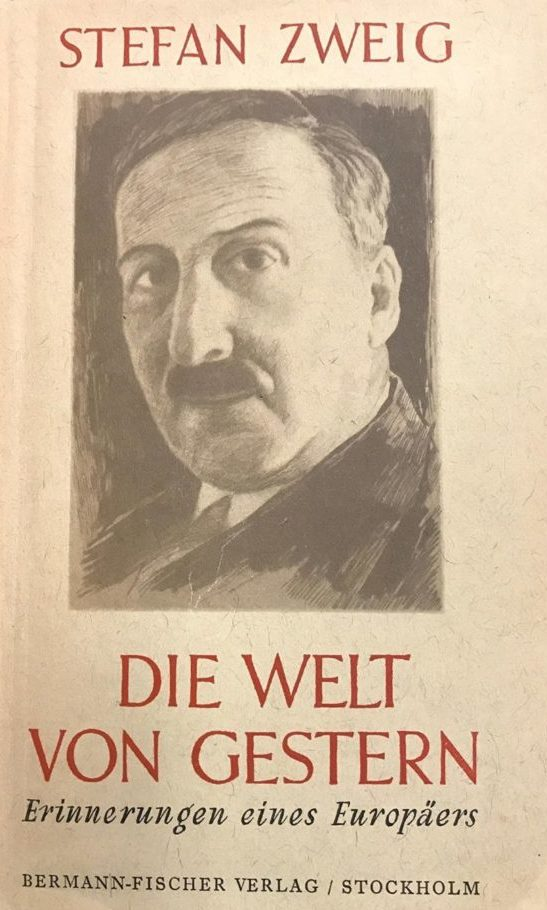

Collage of passport photographs of Stefan Zweig.

PHOTO: COURTESY OF THE STEFAN ZWEIG CENTER IN SALZBURG.

Every day I learned to love this country more, and I would not have asked to rebuild my life in any other place after the world of my own language sank and was lost to me and my spiritual homeland, Europe, destroyed itself.

— Stefan Zweig, suicide note (1942)

Eighty years ago, on a warm February 23, a housekeeper in the Brazilian town of Petrópolis was going about her business, when she noticed that her patrons had slept in remarkably late. It was nearly four in the afternoon when she finally dared to move beyond knocking and opened the door to the couple’s sleeping chambers. She found them both lying on the bed: exiled Austrian writer Stefan Zweig, on his back with his hands folded, and his wife, Charlotte Altmann, nestled against his shoulder. Both were dead—suicide by poison.

Zweig’s final words, which he had written down in a message to the world, were eventually read and widely discussed. As others have noted, they are marked by a seemingly ‘infinite sadness’—a sadness that clearly Zweig himself was no longer able to bear.

To be sure, depression had tortured him for years, stemming from his disappointment with what had become of his Europe in the wake of the First World War. For him, ‘Europe’ was more than just a collection of countries located in close proximity to each other; Europe was the actual shape of his own heart—a cultural or civilizational ideal present in every sentence he ever wrote.

Zweig’s works are free from any pretence. His words are clear and direct—an expression of his unfiltered soul—and they avoid any attempt to impress readers with craftsmanship. It is the power of his own personality that seems to speak to readers to this very day, drawing them into his literary world.

His personality was contradictory and flawed at times; but he was truly and fully human. Zweig’s sensitive nature went hand in hand, perhaps surprisingly, with a deep admiration for the great men of action of history. In fact, the masculine ideal of great deeds and heroism permeated his work as much as tragedy, sorrow, and resignation did.

When we today remember the past’s greats, we tend to reflect on their achievements based on the realities and needs of the present. We therefore cannot avoid seeing the tragedy of Zweig’s life in relation to his lifelong pacifism, a stance for which many of his contemporaries showed but little understanding. Even his friend Thomas Mann admitted, in an essay on the 10th anniversary of Zweig’s death in 1952, that “there were times when his radical, uncompromising pacifism tortured me.” Mann continues:

He seemed willing to permit the reign of evil, if only the most hated thing, war, was avoided. The problem can’t be solved. But after learning that even a just war will bring forth evil, I’m starting to think differently about his past position—or at least I try to.

In Zweig’s autobiographical work, The World of Yesterday: Memoirs of a European, published in 1941, shortly before his suicide, he described the Europe that had been lost. He dreamt of a ‘united Europe,’ seeing it as the only way to avert nationalism and future wars. But contrary to today’s globalist projects, his ideal harked all the way back to the res publica literaria of Erasmus of Rotterdam, a humanistic universalism that most resembled the supranational Habsburg monarchy of his own youth.

But Zweig’s Europe was also more of a spiritual concept than merely an active political body. He despised daily politics and chose to oppose war mongering and politics in general, rather than simply taking sides. Zweig considered the concept of the involved intellectual—the man of letters who takes a political stance—to be a submission of the spirit to the yoke of politics.

In 1935 he wrote a letter to his friend, Nobel prize winner, pacifist, and fellow European Romain Rolland, in which he said: “Politics are making us stupid. They are so disgusting, so absurd, that one can only be saved from them by spitting on them.”

Ever since the outbreak of the first World War, Zweig had condemned the “sudden rapture of patriotism,” as he put it in The World of Yesterday, but he refused to “hate a world that was as much mine as my fatherland.” Instead, Zweig “remained fully determined not to allow this war of brothers, brought about by clumsy diplomats and brutal munitions-manufacturers, to affect my conviction of the necessity of European unity.” Being declared unfit for military service, he instead dedicated his time to what he believed was “the most important service in the war: the preparation for the understanding to come.”

Throughout the war, Zweig never faltered in his quest to promote ‘mutual understanding,’ urging people to remain faithful to friendships beyond borders, promoting reconciliation, and even trying to organize a conference to encourage mutual understanding.

Contemporaries of Zweig regarded this attitude of his to be negligent and naive, even “defeatist,” and many people today might be inclined to agree. But this neglects his insights into—and deep psychological understanding of—the political movements of his time. This is exemplified in his last great work, Schachnovelle (The Royal Game), written in 1941 and 1942.

While it might be easy to accuse a pacifist like Zweig of taking ‘the easy way out’ or cowardly avoiding conflict, this only applies in times of peace and harmony. In contrast, to resist the pressure to join the collective madness of the masses when the fury of war consumes people’s hearts is an entirely different matter. Today, it takes a great deal of bravery to adopt such a posture—as much as it did back then. But when his friends expelled him from their circles for not being patriotic enough—“[c]omrades with whom I had not quarrelled for years accused me rudely of no longer being an Austrian,” he writes, “why did I not go over to France or Belgium?” they asked. Zweig was ready to shoulder the burden of his moral convictions.

Some of the artists and intellectuals held in the highest regard at that time—people like Thomas Mann—criticized and even opposed Zweig’s efforts on behalf of peace during the war. After the war, all of them learned hard lessons from those years and many were celebrated for the insights drawn from the war. Zweig, on the other hand, remained marginalized and isolated. He writes:

From the very beginning I had no faith in victory and was certain of but one thing: that even if it could be achieved by immeasurable sacrifice, it could never justify that sacrifice. But I remained always alone among my friends with this warning, and the confused shouting about victory before the first shot, the division of the spoils before the first battle, often caused me to wonder if I alone were mad among all these wise men, or perhaps alone horribly aware in the midst of their intoxication.

Zweig wasn’t just morally convinced of his cause; he was also a keen observer of what was happening around him, and he named the culprits in that rapidly emerging war:

It lies in human nature that deep emotion cannot be prolonged indefinitely, either in the individual or in a people, a fact that is known to all military organizations. Therefore, it requires an artificial stimulation, a constant “doping” of excitement; and this whipping up was to be performed by the intellectuals, the poets, the writers, and the journalists, scrupulously or otherwise, honestly or as a matter of professional routine. They were to beat the drums of hatred and beat them they did, until the ears of the unprejudiced hummed and their hearts quaked. In Germany, in France, in Italy, in Russia, and in Belgium, they all obediently served the war propaganda and thus the mass delusion and mass hatred, instead of fighting against it.

So Zweig remained isolated in his fight against the war (joined only by a few friends such as Rolland). Nobody heeded his warnings the first time around, and neither did people listen to him when war returned to Europe two decades later. But by then, war had come for Zweig as well who, being of Jewish origin, had to first flee to Austria, only to continue on to London , then the United States and, ultimately, Brazil—an odyssey he referred to in his suicide note, lamenting that his “own power has been expended after years of wandering homeless.”

When Zweig opted to end his life, fearing a triumph by the Axis Powers, he did so “upright, as a man for whom cultural work has always been his purest happiness and personal freedom.” One hopes he found some peace at the very end. What he wrote at the conclusion of The World of Yesterday, suggests as much: “every shadow is ultimately also the daughter of light and only he who has known light and darkness, war and peace, rise and fall, only this one has truly lived.”

Had Stefan Zweig remained alive, he may have deeply appreciated the prolonged period of peace that reigned in Europe after the Second World War. He may even have gone on to appreciate and perhaps even admire the ‘European Project’ that is today’s EU. But being the keen observer he was, he would not have been easily fooled. The threats of totalitarianism—despite the outward appearance of liberal democracy—across the West would not have escaped his attention, nor would have the many imperfections of our current world order.

And with rising tensions within and between the “misled democracies” of today, one hopes for Zweig’s desperate love of a civilized peace and the ‘spirit of Europe’ to inspire us—so that we may perhaps spend a moment in silent contemplation and resist the urge to constant action. Zweig’s call for peace went unheard twice before; perhaps we are now ready to heed his warnings.