When the Queen died in September, the world mourned. This may be a figure of speech, but it is scarcely a hyperbole. Global leaders praised the Queen’s fidelity and dutifulness, while ordinary citizens made gestures of respect and admiration. The president of the United States, a nation created by revolt against the British crown, called the Queen “a steadying presence and a source of comfort and pride for generations of Britons … a stateswoman of unmatched dignity and constancy.” He ordered flags to fly at half-mast on federal buildings for ten days. The president of France, leader of a political elite that defines itself by the Revolution, called Her late Majesty the “Queen of hearts,” and many French mayors obeyed his order to fly their flags at half-mast. Even Vladimir Putin and Volodymyr Zelensky were of one mind in praising the Queen.

This was all remarkable in itself, but in Britain, the Queen’s death created a more substantive, almost tangible, unity. Here there was a shared awareness of shared grief that helped us to remember that we have attitudes and values in common, as we all admired the Queen’s decades of service. One felt oneself using the same language as one’s fellow subjects—‘dutiful’, ‘faithful’, ‘steadfast’—and this spontaneous concurrence of adjectives showed that most Britons had the same sentiments about the Queen. The Queen brought us together in admiration of her, with virtues that conservatives must surely admire.

This raises several questions for conservatives. How did the Queen become such a unifying force? Why was she such an admired head of state? More broadly, what do her life and death tell us about the role that monarchy could and should play in a renewed Europe? This latter question is no longer merely academic. In France and in other countries, the rapidly growing traditionalist-Catholic movements are closely associated with monarchism. In recent years, the beatification of Blessed Karl of Austria has given new momentum to Catholic and conservative monarchism. Indeed even in the United States, traditionalist Catholic websites feature pictures of this long-dead foreign holy monarch.

It is clear that answers to my three questions cannot begin with a theoretical account of monarchy. As the above examples show, the Queen won the affection of the heirs of the French and American revolutions, no friends of the last monarchies of their own. To understand the world’s response to the Queen’s death and what we can learn from it, we must begin with particulars: her character and virtues.

However, this alone will not suffice. When President Biden speaks of the Queen as a “source of comfort and pride” and when President Macron calls her “the Queen of hearts,” the two men are responding to something beyond the Queen’s private virtue. They are noting a unifying political power that the Queen had as a sovereign—a power of a kind that even the holiest of private persons do not have. One could say that they are not talking about her life as such, but rather about her reign. Hence in order to understand the unique phenomenon that was and is Queen Elizabeth II, one must understand her life alongside the British constitution.

We are dealing here with a symbiosis: the constitution formed the Queen, but the Queen, as I hope to show, also renewed the constitution, above all by helping to restore the ancient Christian elements latent within it. My thesis is that we see in the Queen’s reign the authentic Christian idea of temporal power and that it is this idea that has made her reign so attractive to the world. The British constitution was like a mediaeval beacon from the Christendom of old, partly bashed out of shape by the years, and the Queen was the flame with the virtue to make it take light again, and shine bright across the world.

One must talk of the British constitution with care. It is not something that one can point to, like the Queen or the Magna Carta. For the purposes of this essay, I will focus on two things that I take to be important components of it: the coronation rite and the attitudes and expectations of the public.

First, let me turn to the Queen’s life and to her constitutional reign. Both, I believe, were defined by a pledge that she made in 1947, at the age of 21. Part of this pledge is well known, but here I want to present a more extended quotation of it than is usual.

There is a motto which has been borne by many of my ancestors—a noble motto, “I serve.” Those words were an inspiration to many bygone heirs to the Throne when they made their knightly dedication as they came to manhood. I cannot do quite as they did.

But through the inventions of science I can do what was not possible for any of them. I can make my solemn act of dedication with a whole Empire listening. I should like to make that dedication now. It is very simple.

I declare before you all that my whole life whether it be long or short shall be devoted to your service and the service of our great imperial family to which we all belong.

But I shall not have strength to carry out this resolution alone unless you join in it with me, as I now invite you to do: I know that your support will be unfailingly given. God help me to make good my vow, and God bless all of you who are willing to share in it.

These words reveal the extraordinary spiritual maturity of the 21-year-old princess. First, note her complete embrace of the life to which God called her. For us today, who remember the Queen as a superb and beloved ruler, it is easy to forget just how daunting a vocation this was. The young Princess Elizabeth was called to rule over a waning empire, over a country virtually bankrupt after the war, under constant scrutiny, privileged but in practice the tool of the government. Worse still, she would have to rule as a woman in a world of male leaders.

At 21, the Queen embraced this vocation. She would not covet the nature and powers of men, but would reign confidently as a woman: “I cannot do quite as they did.” She did not shirk from or resent her duty, but devoted her whole life to the service of our one “family.” As queen, she was to do this duty, year after year, decade after decade, without complaint: at the parade ground and at the village hall, at dinners with old enemies and friends alike, at home and far abroad. She served for life in accordance with her oath, never retiring, never abandoning us when she was needed.

Yet even in this early speech, there is something more than duty. A queen’s duty is to attend certain events, perform certain tasks, and to meet certain people with good grace. Princess Elizabeth made a pledge to do something more: to serve like a knight of old. Her words were significant. Knights were expected not merely to perform certain tasks, but to do so prayerfully and charitably, seeking to grow in natural and supernatural virtues. That is why every knight kept a night-long vigil in church on the eve of his knighting, praying at the foot of an altar. His commitment was not just to duty, but to duty raised up by the grace of Christian charity—in other words, to the peculiarly Christian vision of loving service. “Whosoever will be great among you, let him be your minister.” The strong and powerful knight was to be a servant, especially of the weak and helpless.

In her speech, Princess Elizabeth vowed the same Christian loving service to her subjects. She promised to take an interest in the 50th dignitary, to smile at the 100th handshake, to be always good-natured and encouraging to her subjects. The Queen made good on her vow magnificently. But for that very reason it is easy to forget that loving service is very difficult indeed. One cannot merely choose to be charitable as one can choose whether to wear red or black socks—a choice that involves no self-denial, no discipline, no pain. On the contrary, even the humblest of us sometimes find it excruciating to be charitable; criticisms and complaints broil within us, and we feel ourselves victims to such absurd gnawing injustices that it would (we feel) be madness to remain good-tempered in the face of them.

If charity is difficult for us, how much more difficult it must be for a queen! To meet hundreds of thousands of people a year, who all look to one for reassurance, would fray anyone’s nerves and test anyone’s patience. Yet the queen became a model of loving service. She formed a habit of charity, and so came to make charity look easy. From this habit of charity arose her famous smile, and the evident unfeigned happiness-in-service that so endeared her to the world.

The Queen formed this habit of charity through persistence. But how did she manage to persist? Here we begin to see how the Christian ideal of monarchy shaped Elizabeth’s outstanding life. To remain charitable one must identify the complaints broiling within oneself and fight them down when they seem to define one’s world. To do this one needs a firm resolution, grounded in a love that transcends the indignations of the moment. But the only truly transcendent love is the love of God. Hence no one can, I think, deny that the Queen’s charity flowed from her faith. Christians will also call it the fruit of grace.

This is one reason why Queen Elizabeth won the world’s admiration. But this explanation of the world’s love for her invites a further question: What inspired her vow to uphold the ideal of the knight-like servant-monarch? In part, the answer is: her parents. Happily and faithfully married—and themselves both children of happy and faithful marriages—the Queen’s parents had a deep Christian faith. This faith bore fruit. In the Second World War, the couple bravely and lovingly served their people, visiting bombed-out houses during the Blitz and refusing to retreat to the countryside for safety.

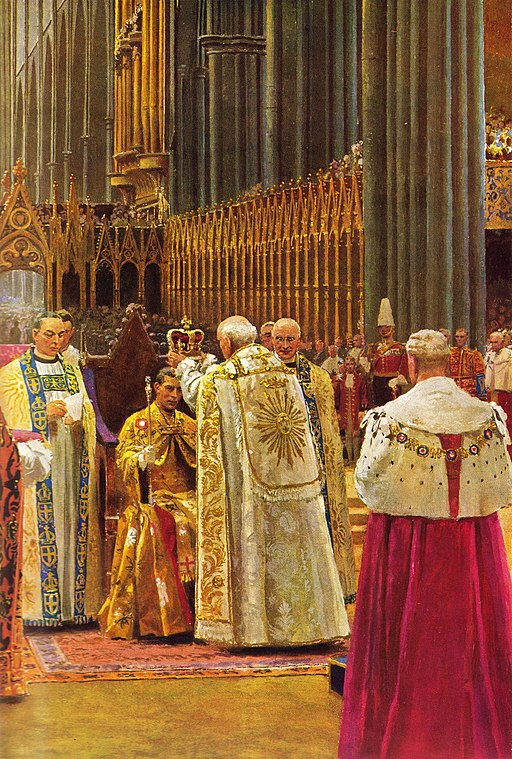

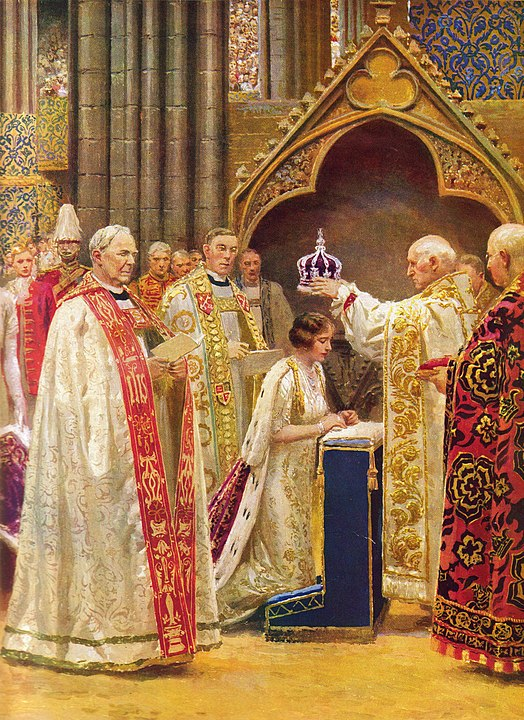

If her parents embodied the ideal of servant monarchy for the young Princess Elizabeth, she already knew that this ideal had deeper roots in the British constitution, particularly in the coronation rite—a rite which she had seen performed for her father and mother when she was 11 years old.

At their coronation, the Archbishop of Canterbury placed a ring upon the fourth finger of the right hand of each of her parents—the same finger upon which a bishop’s ring or a nun’s ring is worn, and upon which wedding rings were also formerly worn. The prayer said during this ring-giving dates back to the Middle Ages:

Receive this Ring, the seal of a sincere Faith; and God, to whom belongeth all power and dignity, prosper you in this your honour, and grant you therein long to continue, fearing Him always, and always doing such things as shall please Him, through Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

From the tone of this rite, it is clear that the mediaeval Church understood it to be analogous to the ring-giving that forms part of the rites of matrimony and episcopal ordination. It was seen as effecting a quasi-sacramental, ideally lifelong, bond of love, service, and fidelity between monarch and people. Indeed, this bond was seen as defining the monarch’s life and his pursuit of salvation. The modern coronation rite that Princess Elizabeth witnessed conveyed the same ideas, and so provided a template for a distinctive kind of holy life: the life of the holy sovereign. The Queen built her life on this template. She accepted this bond and allowed it to define her, realising the ancient ideal of the grace-filled sovereign. Thus, she brought renewed life and significance to the ancient ritual.

If we turn again now to Princess Elizabeth’s declaration, we can see how it beautifully summarises the mediaeval ideals of monarchy expressed in the coronation. The Queen spoke of knightly service and her “solemn act of dedication.” A knight was solemnly dedicated in a special Christian rite, in which the Church confirmed his knighthood, blessed him, and set him apart. Since the earliest recorded English coronations, the monarch has been similarly confirmed, blessed, and set apart, not only by investiture with a ring, but by the sacred act of anointing. In the Middle Ages, this anointing was understood as a sacramental. Though this understanding was rejected at the Reformation, much of the modern rite of anointing remains mediaeval, with some phrases dating back to the 9th century, and it retains its sacral atmosphere. The choir sings the solemn anthem “Zadok the priest and Nathan the prophet anointed Solomon king,” and then the Archbishop of Canterbury says: “Be thy Head anointed with Holy Oil, as kings, priests and prophets were anointed.” The Church confirms and blesses the monarch’s power, setting him or her apart for the task of ruling.

Here again we have a latent mediaeval aspect of the constitution that the Queen embodied. The Queen was loving and devoted, but she also knew that she was set apart, made holy, and in public she retained a certain detachment, never showing us too much of her private feelings except where those reflected the common feelings of the nation. This, too, was part of what made her loved and great: in a self-indulgent, emotive age, she was not too ‘touchy-feely’; she did not ‘overshare.’

As we have seen, the Church blesses the monarch and sets him or her aside for the task of ruling. In other words, the monarch is not automatically sacred, but becomes so through the sanction and blessing of the Church. This has an important implication. As the German historian Onno Klopp observed in 1891, the meaning and the motive of every mediaeval Western coronation rite consists in this, that the monarch goes to the Church as to a separate authority, to crave her approval. The rite implies the limitation of his power: he cannot teach or enforce faith or morals. It also reminds us that he remains subject to the moral law, by reminding us that the Church has the authority to rebuke him if he breaks it. The rite thus embodied Pope Gelasius’ doctrine that there is a spiritual auctoritas and a temporal potestas, both of God, neither absolute—a doctrine that defined the politics of mediaeval Christendom.

In Britain, this notion of the Church’s separate authority of course became weaker after the Reformation, and many coronation prayers were revised to water-down the conspicuous Gelasianism of the old ceremony. (For example, in the above-quoted “prophets, priests, and kings” from the rite of anointing, the word “priest” is a post-Reformation insertion, intended to insinuate the monarch’s right to govern the Church). Nevertheless, the old notion of the Church’s independent spiritual authority remains implicit in the modern rite as used for Queen Elizabeth and her parents. The Archbishop of Canterbury does not consent to anoint the sovereign until he has made him or her promise to “cause Law and Justice, in Mercy, to be executed in all your Judgements,” and to protect the Church of England. Symbolically, the monarch still has to satisfy the archbishop before he favours him or her with anointing.

The Queen embodied this implicit Gelasianism. She understood that her power, though sacred, was limited. She did not tell her people how to live or what to believe. She knew that she was subject to the moral law, and she sought to be virtuous. She also respected the Church of England, never interfering in its internal doctrinal disputes. She was faithful in the way proper to an ordinary layman, and this proper fidelity was the basis of her much-celebrated life. Here again, she brought a mediaeval constitutional ideal to life.

The young princess’ remarkable birthday speech has one more thing to teach us. In it, she declared that she needed the support of the people of the empire, and invited them to share in her vow. Here again she conveyed an ideal that forms part of the British constitution and which is more fully expressed in the coronation rites. In the modern form of these rites, the king—standing on a specially-constructed temporary platform called the theatre—shows himself to the people at each of its four corners, while the archbishop asks “All you who are come this day to do your homage and service, are you willing to do the same?” Before the Reformation, the archbishop’s enquiry was sharper and more prolonged, but the modern rites still convey the principle of monarchy by consent.

This principle is an ancient and enduring component of the British constitution. Though the institutions that claim to represent the popular voice have changed, monarchy in Britain remains a conversation between people and sovereign, not a monologue. There is a sense in Britain that the people have the right to hold the monarch to his or her holy bond, to demand that he serve them as they want to be served. In the Queen’s reign, we saw this most clearly after the death of Princess Diana. Immediately after her death, the Queen remained with her family at Balmoral Castle, where she had been spending her summer holiday. It is well known that she thought it important to protect the privacy of Princes William and Harry. Yet the people, stirred on by Tony Blair and the media, became restless. Popular newspapers demanded that the Queen travel to London, accusing her of heartlessness. The people wanted the Queen to lead them in grief, and it seemed that she was unwilling to do so. For a few days, one felt that the position of the monarchy was precarious: not because there was any threat of a revolution, but because the monarchy was losing the popular support that everyone agreed it needed if it was to survive.

Under this public pressure, the Queen came down to London earlier than planned, and led the people in grieving, with a walkabout and a well-judged speech that renewed the bonds of affection between people and sovereign. She did not what she wanted, but what the people wanted. For she understood that her power, though anointed and consecrated, nevertheless rested on her claim to represent and serve her people in accordance with their will.