Water, yeast, flour, salt. Nothing more, but nothing less, is required to obtain that absolute summit of art and gastronomy, the French baguette. 250 grams of perfection and ultimate bliss. Dare we say it: a foretaste of heaven.

Perhaps though, we might remember that something more is needed to bring it to fruition: centuries of patience and love, of savoir-faire and art de vivre. This is called civilisation.

UNESCO has finally made the baguette a part of the universal consecration that is the inscription on the intangible heritage of humanity, where it joins, in no particular order, the construction and use of expanded monoxyle dugout boats in the Soomaa region in Estonia and the Croatian dances of Saint-Tryphon. It is about time.

Yet when we heard this good news, we couldn’t prevent ourselves from being worried. Isn’t classification by UNESCO a form of sacralisation of endangered masterpieces? Like historical monuments, only those material objects that suffer the ravages of time and are threatened with extinction deserve to be pinned to the pantheon of universal human glories, before they become nothing more than a distant memory that we evoke with a trembling voice and a sigh.

In the 1990s, the baguette almost disappeared. A not so distant time, that of the childhood of the modest author of these lines, who remembers when it was sometimes necessary to travel miles to find the rare object—a baguette with a golden crust and crispy as desired, with a delicately honeycombed crumb, with a soft colour slightly tending towards bistre.

An advertising campaign by the bakers’ guild sounded the alarm, with this alarmist slogan: “When tradition disappears, you’ll want it.” A child was seen bending over a boiled egg with a sinister plastic straw in it, looking puzzled. A soft-boiled egg without any mouillette, that little piece of crunchy, melting bread that is coated with the freshly-spun yolk … It was a vision of the apocalypse.

Fortunately, French bakers have rolled up their sleeves and (re)brought to life this culinary treasure that is the baguette, now stamped with the sweet term ‘tradition’: the ‘tradi,’ as it is called in all good bakeries. Today, it can be found almost everywhere, and this is fortunate.

As the president of the Confédération nationale de la boulangerie-pâtisserie française (CNBPF) points out with some humour, the UNESCO jurors did not have to go far to recommend them. UNESCO is based in Paris, and “all the members of the committee have already been to a bakery.” In Paris, despite Anne Hidalgo’s progressive efforts, there are still traditions that resist, and on every street corner you can acquire, for the modest sum of one euro and a few cents, a piece of happiness and eternity. These gentlemen of UNESCO have had plenty of time to convince themselves, week after week, of the quality of the French baguette’s candidacy.

On Sunday mornings, you have to queue up to get your baguette. Some people ask for it to be “not overcooked,” which is a heresy in itself: a good baguette should be golden. But the baguette is a good girl, who can be tamed in all its forms and colours. The Parisian baguette is whiter and softer; the ‘tradition’ one is more consistent and crunchy. A matter of taste.

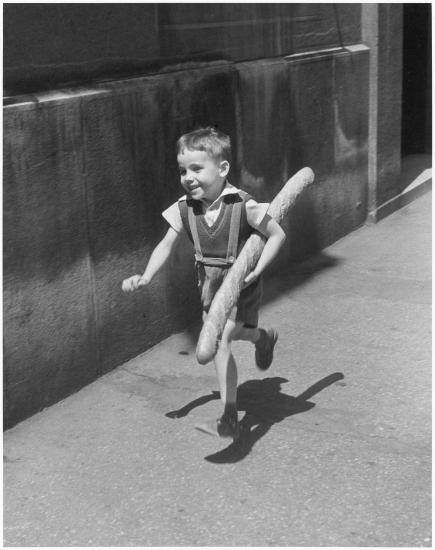

As soon as the threshold of the bakery is crossed, the little pink-cheeked Parisian, immortalised by the talented photographer Willy Ronis, will rush to bite into the quignon, i.e., the end of the baguette that concentrates all the crunchiness of which it is capable. The child runs, because he is expected at home. But his impatient mother is careful not to scold him when she retrieves the bread from the little child’s handcuffs. Nibbling on the baguette on the way home is not a crime, it is a duty, almost a ritual. If the bread is hopefully still warm, it would even be a sin not to honour it in this way.

The baguette is therefore protected. Let us rejoice!

But its existence, thus confirmed by administrative means, could be attacked in a more insidious but very real way. The baguette is suffering from competition from supermarkets which, for a few cents, deliver a sort of flaccid sponge under the name ‘baguette,’ just good for scrubbing the kitchen sink. Making a baguette takes time and effort—two things that our contemporary civilisation detests. As a result, bakers are becoming increasingly rare. France had 50,000 bakeries in 1950; today, 30,000, which means that there is now less than one per town. This is the real tragedy. And if the baguette is resisting, what can be said of whole sections of French gastronomy, of which it is an inseparable companion, but which are under repeated assault from mass-produced food, without smell or taste? What’s the use of having a nice baguette, if you can’t dip it into the rich sauce of a daube or a blanquette, which have now disappeared from the menus of many French brasseries? The gastronomic meal of the French was inscribed on the list by UNESCO in 2010. Since then, it has been on a slow but sure decline.

Let us nevertheless try to see things from the right side of the baguette. Willy Ronis immortalised the laughing child in 1952. Today, in 2022, I personally know some mischievous little guys who continue to perpetuate the ceremony with great application. Deo Gratias. In this respect, succession is assured!