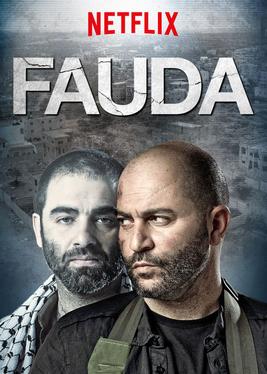

When a cultural product exploring a given conflict draws contradicting reviews from each of the conflict’s sides, could that contradiction simply be proof that the conflict in question is beyond repair? With season four released with roaring success a fortnight ago, the Israeli Netflix thriller Fauda is again exposing the zero-sum nature of the Israeli-Palestinian quagmire, with the show’s every step to humanize one of the conflict’s camps unfailingly met with the other side’s accusations of impartiality. For those inclined to view Israel’s 56-year occupation of the West Bank (and formerly Gaza) as an illegal affront to Palestinian statehood, Fauda amounts to ultra-Zionist propaganda, a one-sided military epic whitewashing the Israeli army’s (IDF) abuses whilst unfairly typecasting every Palestinian as a would-be terrorist. For those who instead view Israel as a commendable liberal democracy lacking an honest partner for peace on the Palestinian side, Fauda’s effort to humanize the country’s terrorist enemies is a step too far in the other direction. So, which is it, Lior Raz and Avi Issacharoff?

These dueling narratives seem even more starkly conflicting in view of the show’s acclaim beyond Israel and Palestine. Befuddlingly to both sides, scores of international reviewers have taken to praise Fauda’s evenhandedness. Every last character, they claim, is depicted in the same human light, the Palestinian terrorists no less than the Israeli units chasing them down. In 2017, the New York Times—no friend of Israel lately—named Fauda the year’s best show. Avi Issacharoff told The Atlantic around that time that Fauda “is a TV show, not a political manifesto.” In season four, Issacharoff and his co-screenwriter Lior Raz take the show internationally, but the dissonant echoes that have been stalking them for the prior three seasons follow in their footsteps. If their assessments of a show that admittedly couldn’t have been more neutral are so plainly at odds, could it be that the antagonists simply cannot agree on anything? That there’s no overlap in the Venn diagram? Put otherwise, could Fauda prove the clearest testament yet to the Palestinian question’s irreducible unsolvability?

In 2018, following Fauda’s global Netflix launch (the show had aired on Israeli TV previously), the anti-Zionist—and admittedly antisemitic—Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) campaign lashed out against it, labeling it a “racist, anti-Arab propaganda tool that glorifies the army’s crimes against Palestinians.” “By sanitizing and normalizing these crimes,” their statement went on, “Fauda is complicit in promoting and justifying these human rights violations.” With season four taking the plotline to Brussels and Lebanon as part of a duel between Doron Kabilio’s Mista’arvim unit and Hezbollah, Israel’s presence beyond the 1967 green line lays distant—yet the show hasn’t earned new friends either. In seasons one, two, and three—successively about lone wolves in the West Bank, a Palestinian antenna of ISIS, and the Gaza-based Hamas—the operations of Doron’s unit are indeed depicted gruesomely, with torture, hijacking, and killing all par for the course. Yasmeen Serhan of The Atlantic dismissed Fauda as “a disappointment for those who expected a Palestinian perspective.”

These critiques are the obvious tradeoff for adopting Doron’s viewpoint, and even that doesn’t exclude love affairs with Palestinian characters, including, in this latest season, an Arab IDF soldier who ends up a snitch. At any rate, the anti-Israel charges of impartiality are easily countered with the screenwriters’ background. Both Raz and Issacharoff’s Zionist beliefs survived active duty, something increasingly rare in the post-Second Intifada. Raz grew up in a settlement and lost his girlfriend of three years to a 1990 stabbing by a Palestinian lone wolf, who was swapped a decade later, along with scores of others, for IDF prisoner Gilad Shalit. Issacharoff traces his roots in the Holy Land back 140 years to the earliest Bukharin settlers of Jerusalem’s namesake quarter. Both are Mizrahi, meaning their view of the Palestinian question is likely tainted by the pogroms and persecution that ethnically cleansed Jews from the Arab world throughout the ’50s and ’60s (Raz’s parents came from Iraq and Algeria). In 2018, Raz told Memo: “I can’t take [out] the warrior inside me. I am a Zionist and must protect my friends and family.”

Yet in a paradox far too typical of modern Israel, this is precisely what qualifies Issacharoff and Raz to offer the Palestinian perspective that Serhan longed for in The Atlantic. Thanks to Palestinian kids playing near his settlement, Raz is fluent in Arabic, as is every one of Doron’s colleagues, though in a slightly accented manner according to some Arab sites. When Sagit and Nuri marry in this latest season, the crew appears at the wedding dancing to Oriental tunes. After the army, Issacharoff launched into a distinguished journalistic career across Israel’s liberal media, authoring several bestsellers and rising to become one of its foremost experts on the Palestinian question. This is what earned them the suspicion of the country’s arch-nationalist quarters, and the categorization of their show in the “shooting and crying” genre, a category populated by West Bank reservists deeply critical of Zionism. Raz himself was upfront in a 2018 interview with the CJS: “I wanted to get everything off my chest,” he said about his post-military PTSD and the fallout from his girlfriend’s assassination.

This points to Raz’s ultimate purpose in writing the show. In a videotaped interview with an unnamed attendee at a recent film festival in Los Angeles, the screenwriter claimed that Fauda depicts the “human toll” the conflict takes on all those involved, in the hope that a shared narrative can emerge regardless of one’s political priors. This is doubtless a lofty aim, one that could point to a resolution of a conflict that’s gone on for far too long. This innocent ambition amounts to the show’s distinctive quality, yet also its ultimate vulnerability. Amongst the world’s conflicts, Raz and Issacharoff couldn’t have chosen a more treacherous clash of competing narratives from which to weave a synthesis. If the show seemed like a chance to reconcile narratives, the conflict’s sides have been depicted as hopelessly irreconcilable. Granted, both are portrayed as humanly flawed—the Palestinian Authority as hellishly venal, and the Israeli Defence Forces as ruthlessly brutal. The catch is in the show’s choice to humanize groups whose humanity the other side has built its entire narrative on negating.