It is a big mistake to think that female employment can only be approached from a gender perspective. Nor should we confine our thinking to the gender frames that feminists wish to impose, as well we should not yearn for the idealistic vision of the woman who is financially supported by her husband (which might have never existed, or at least which is available to very few). Throughout our history, women have worked just as hard as men to provide for the family.

In what follows, we want to shed some light on the context of women’s employment that may put the issue on the horizon of conservative thinkers.

Shifting focus on the labour market

In most European countries, there was a conceptual shift in employment policies after the 2008 financial crisis. While governments had previously focused on reducing unemployment, in 2008 the emphasis shifted to increasing employment. For example, Hungary used to be a welfare-based society, but in 2010 the Orbán government radically changed the approach and set itself the goal of creating a work-based society. They aimed to increase the number of employed people by one million in ten years, despite the fact that Hungary had the lowest employment rate in the EU.

This seemingly impossible target was met; Hungary had one of the highest rates of employment growth for both women and men in the European Union. Nearly a million employees were added to the workforce, adding up to 4.7 million. Unemployment has fallen from 470,000 to less than 200,000. The employment rate for people aged 20 to 64 has risen to over 80% and the unemployment rate has fallen to less than 4%.

Almost everywhere else in Central Europe, growth is above the EU average. As a result, incomes have risen, far fewer people are now on social benefits, the proportion of people at risk of poverty and social exclusion (see AROPE indicator) has fallen in the region, and fertility has increased significantly in these countries.

Connecting birth rate and employment

There has always been a consensus among fertility experts that an increase in full-time employment for women reduces the birth rate. However, over the last three decades, Central European countries have exhibited the opposite trend. Here, fertility rate falls when female employment rates fall.

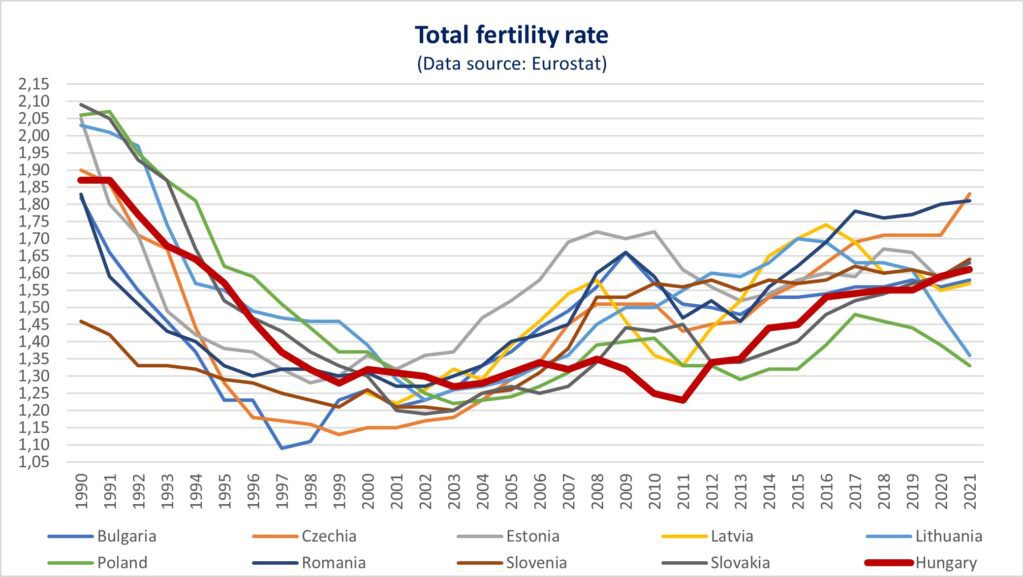

After communism retreated, the birthrate in these countries fell sharply from around 2 to below 1.3 within a decade.

During that time period, Central Europe was drained of employment. Nearly one and a half million jobs were lost in Hungary alone. In the Eastern bloc countries, the communist regimes made it compulsory for everyone to work. For nearly fifty years, there was no legal unemployment in these countries. After the fall of these regimes, the number of people who lost their jobs reached enormous proportions. Real earnings fell sharply, and poverty threatened a large proportion of the population.

Women in the region started to work full time in the 1950s The two-earner family model was common, as both parents were forced to earn in order to make a living. This is why job losses were a major crisis, and fewer and fewer people had children in a precarious situation. At first, many couples chose to postpone having children, and then many had to give them up because of the biological constraints of the delay.

The lowest fertility rate in the history of the European Union was 1.09 in Bulgaria in 1997. Previously, it was also unimaginably low in other countries in Central Europe with the Czech Republic at 1.13 in 1999, Slovakia at 1.19 in 2002, Slovenia at 1.2 in 2003, Latvia at 1.22 in 2001, Lithuania and Poland at 1.22 in 2003, Romania at 1.27 in 2002, and Hungary at 1.28 in 1999.

Living conditions and employment—including for women— improved after the turn of the millennium and after accession to the EU. This improvement was accompanied by an increase in fertility. The only exception was Hungary, where the rise in the birth rate at the turn of the millennium was very short lived. After 2002, there was a further decline, which reached a low of 1.23 in 2011.

Twenty years ago, the countries of Central Europe had the lowest birth rate in the European Union. The region has seen the greatest improvement in recent years, with six countries reaching their highest post-regime increase in fertility rates in 2021. The Czech Republic has the second highest fertility rate in Europe with 1.83, followed by Romania with 1.81, with 1.64 in Slovenia, 1.63 in Slovakia, and 1.61 in Hungary. In these countries, female employment is also at its peak, the at-risk-of-poverty rate is much lower, and real earnings are rising steadily.

Unfortunately, despite these facts, there is still a strong belief that full-time female employment reduces birth rates. As we can see, this has been contradicted in recent decades by the countries of Central Europe. Here female employment has increased significantly, in some countries either reaching or exceeding the levels before the fall of communism around 1990. Almost all of these increases were accounted for by full-time workers, and in parallel with this process, birth rate has also risen enormously.

The employment expansion has taken place at a time when a large portion of the population is aging and declining everywhere in Central Europe. When more people work, more people pay into pensions and social security. Since the region has had a Prussian-based, directly funded, pay-as-you-go pension system for nearly a hundred years, this means that the state provides pensions for inactive elderly people from the contributions of the working population. However, this system can only work if the number of employed are far more numerous than pensioners. This is why it was crucial to widen the pool of workers as much as possible.

So the increase in women’s employment is not merely a gender equality issue, as feminists claim. It is needed to maintain the pension system on the one hand and the standard of living of families on the other. It is important to note that couples in this region will have more children if both parents have a secure income.

Other regions in the European Union do not have such a high level of birth-rate improvement. For example, fertility rates are only 1.13 in Malta, 1.19 in Spain, and 1.25 in Italy. But over the past decade, Finland, Denmark, Sweden, Ireland, the Netherlands, and even France have seen a serious decline in this rate, despite all of them increasing female employment. In these countries, the correlation found in most of the literature is that more children are born when the mother is not working.

Thus, paradoxically, in Europe, there are examples of both correlations at the same time, i.e. some countries where female employment is a barrier to fertility growth and others where it is a condition for it. Recognising this link will bring us closer to solutions that can help to make our societies more sustainable. Today, fertility is increasingly seen as a primary economic indicator, as it responds to changes before full changes in income and employment occur.