I sometimes get questions about why my forecasts are so different from those published in mainstream media. I have three answers to those questions, the first being a question: if ten people tell you that the Earth is flat, and one says the Earth is round, who is right?

My second answer is to point to the many instances where my forecasts have been correct. In direct opposition to especially conservative economists, I predicted already last winter that the U.S. economy was not going to go into a recession this year.

My third answer is the long one. I do not use econometrics for my forecasts. I use the theory and methodology of political economy.

Elaborations on what that means in detail are well suited for closed-door seminars at economist conferences; for the public discourse, there is a more interesting way to explain my different approach to forecasting. Let me illustrate this with reference to the U.S. economy; we could talk about Europe, but there is very little disagreement that Europe is going into a recession. There are still considerable disagreements over where America is heading.

A recent analysis of the economy in the Wall Street Journal serves as a good example of how mainstream economists think, especially those with a conservative slant. By using it as an example, I do not mean to pick on either the Journal or conservative economists; this newspaper just happens to be widely read and have considerable credibility. It is also popular among conservatives, who—I have to note—seem to be more inclined to talk down the U.S. economy because we have a Democrat president.

I don’t like bias of any kind in economic forecasting. Sadly, there was plenty of that in an article in the Wall Street Journal’s weekend print edition of November 4-5th. Under the headline “Hiring Slowdown Signals A Cooling Economy,” (subscribers can read it online) the article starts boldly:

Job growth slowed sharply last month, a sign the U.S. economy is cooling this fall after a torrid summer. Employers added 150,000 jobs in October, half the prior month’s gain and the smallest monthly increase since June

The first thing a forecaster needs to learn to do is to study trends. One month’s worth of numbers is of no use without the context of a trend. As it happens, I provided that context two weeks ago, when I explained how the September jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showed a strong U.S. economy. I followed up last week with more context: an analysis of the latest GDP data, which confirmed my positive assessment of the U.S. economy.

To be fair, the Wall Street Journal does not explicitly state that the October jobs report says we are in a recession. However, they do say that the report

suggests a downshift in a labor market that outperformed expectations for most of this year. Now employers are pulling back in light of high interest rates, persistent inflation and wars in Europe and the Middle East.

Here, their outlook on the U.S. economy makes a second error: speculation over cause and effect. They propose three reasons why the jobs growth is weaker than in September, without trying to explain how those causes would have that effect.

Their first cause, high interest rates, has no empirical merit. As I explained last week, consumer spending, especially on credit-financed items, has actually been doing well recently. Adjusted for inflation, last quarter’s spending on consumer durables was up by an annual 4.6%. When consumers spend more money on durable goods, neither retailers who sell them nor importers or manufacturers who provide them have any reason to ‘pull back’ hiring, as the Wall Street Journal suggests.

I also noted last week that after a slump in 2022, business investments were showing a comeback: the volume of business capital formation in the third quarter was 0.6% higher than a year earlier. This is a small increase, of course, but it breaks with the decline that dominated 2022 and early 2023. Since many such investment projects are financed with credit—especially among smaller businesses—these positive numbers directly contradict the Wall Street Journal.

As its second reason why a recession is coming, the Journal points to persistent inflation. It is true that inflation is a bit persistent, with consumer prices rising at 3.5-4% per year. At the same time, the Journal—again—fails to contextualize: over the past 18 months, inflation has been at least twice as high as it is now.

The Journal’s lack of explanation for the link from inflation to weaker jobs growth becomes even more glaring given that entrepreneurs, investors, and households all prefer predictable inflation to unpredictable inflation, even if the unpredictable one on occasion is lower. Research by Daniel Kahneman, the 2002 Nobel Memorial Prize Laureate in Economics, among others, indicates that if a rapid rise in inflation is followed by a rapid decline, the decline may not at all have the substantially positive effect on economic activity that standard economics would have us believe. Until inflation stabilizes, its sharp swings are perceived as price volatility, which is bad for economic confidence.

In other words, the Wall Street Journal’s second reason why the disappointing October jobs report would cause a recession is for the most part incorrect.

Their third reason is the most speculative of them all. I highly doubt that a repair shop for agricultural machines in Iowa would stop hiring new mechanics because Israel has troops in Gaza. I also doubt that a bank in Montana would stop hiring new tellers because U.S. warplanes have struck targets in Syria.

After having failed to look at trends and failed to explain its assertions, the Journal resorts to outright obfuscation of facts:

Moreover, just three sectors—healthcare, government and leisure and hospitality—accounted for nearly all the job gains, leaving the rest of the overall economy with no net job growth. This contrasts with the more broad-based hiring seen earlier this year.

What is not mentioned here is that the jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics clearly notes: “Employment in manufacturing declined due to strike activity.” The table that the BLS report relies on shows that due to the strike, the manufacturing industry as a whole suffered a net loss of 35,000 jobs in October. That number is almost entirely attributable to the auto industry.

In plain English: if the United Auto Workers had not called out its members on strike, the U.S. economy would have seen a net gain of 185,000 jobs. This is 23% more than the number now reported.

The auto strike will have a similarly distortionary effect on the jobs report for November when the auto industry opens up again.

Then the Wall Street Journal goes back to presenting factoids without context:

Average hourly earnings rose 4.1% from a year ago, down from 4.3% in September. Wage gains have been slowing since March 2022, when annual raises were near 6%.

By choosing March last year as the point of comparison, the Journal gives the impression that the current wage gains are a sign of a weakening economy. They are not. For the past 30 years, the normal inflation rate has been in the 2-3% bracket. In good times, wage gains were for the most part only marginally higher than that.

To this point, as I explained two weeks ago, over a four-year horizon—covering both the pandemic and the high-inflation episode that followed—the average American wage earner has actually seen his real wage grow by 2.6%. This is a meager number, given that it stretches over four years, and it is definitely no cause to celebrate the performance of the U.S. economy. Nevertheless, together with inflation rates a little bit below 4%, it indicates that the wage gains reported by the Wall Street Journal are good enough to keep the American consumer in reasonably good shape for the winter.

There is a lot that the Journal does not tell its readers, but among the more notable absentees is the point that the decline in inflation works as a confidence booster and even a stimulus for the economy. For the most part, advances in money wages in response to high inflation will remain in place as inflation winds down. This means that the purchasing power of large numbers of Americans will improve over the coming year; a return to low inflation works as an indirect stimulus for the economy.

Another indirect stimulus is the coming decline in interest rates. It has not really started yet, and the Federal Reserve still claims that it is more likely to raise interest rates than to lower them. However, given that inflation does not take off again—and short of a full-scale war in the Middle East, I see no reason for that—the Fed will shift its focus to a plan for lowering rates. They could start as early as the first quarter of next year, but more likely, they will wait until later in the spring. When it happens, though, it will offer higher-paid workers a chance to refinance their homes at lower interest rates, buy a new car at lower rates, and even obtain other forms of consumer credit that are currently unattainable because of high interest rates.

Access to cheaper credit means lower monthly payments on installment loans. This lower cost is technically (though not formally) a real wage booster for consumers; when consumers pocket more money per month, they can increase spending, invest more, and thereby help boost long-term macroeconomic activity.

Again, as things look now, interest rates are unlikely to come down within the next 4-5 months, but if inflation gently comes down toward 2.5-3% and an emerging trend of declining interest rates continues, the Federal Reserve will cut its federal funds rate in good time before next summer.

The trend of declining interest rates is not yet very visible, but we can see the elements of it in the markets for U.S. government debt. To take three examples from the secondary, i.e., open market for U.S. Treasury securities last week:

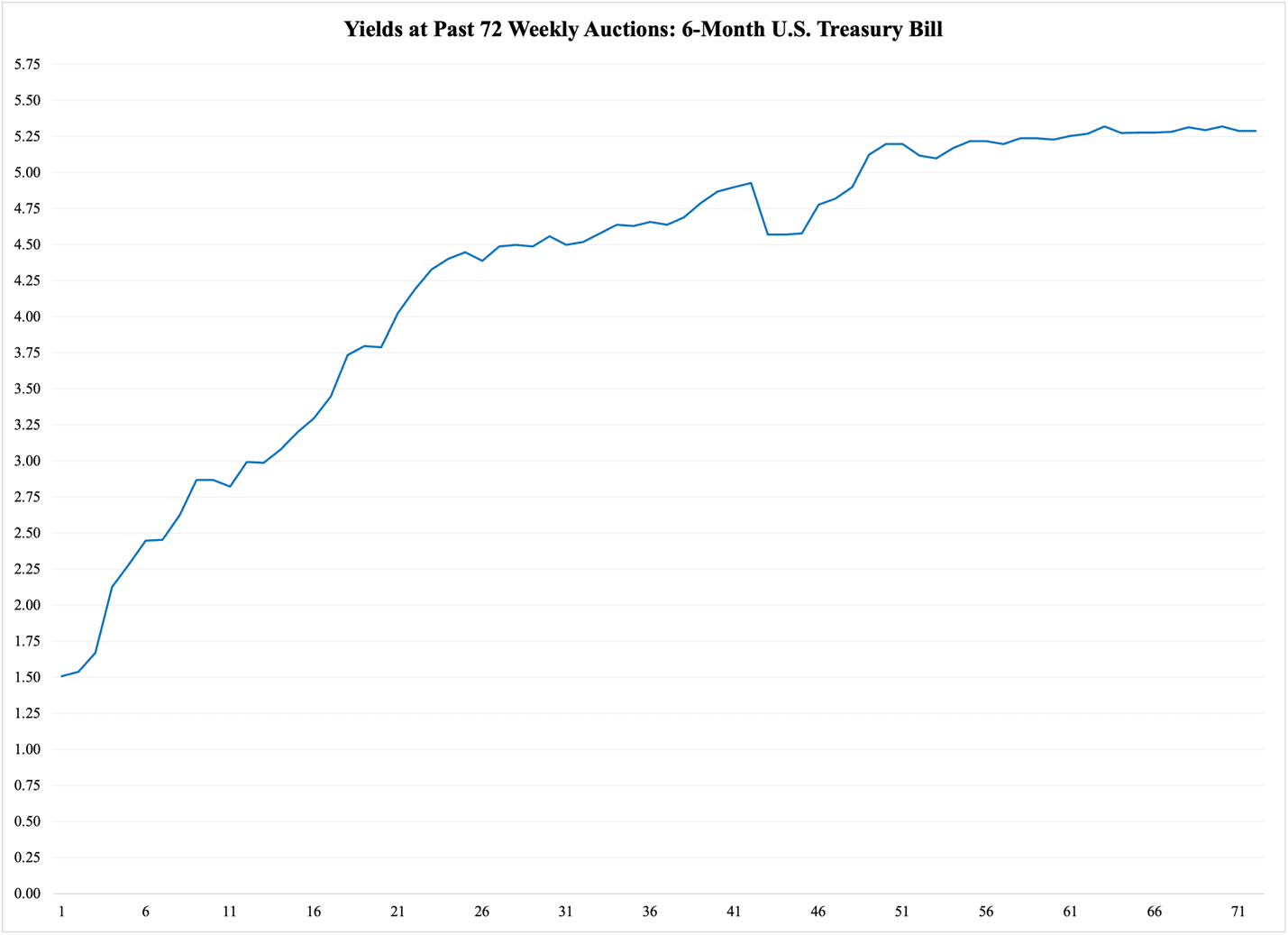

In the primary market, namely, the market where the U.S. Treasury sells new debt at auctions, interest rates have peaked and even ticked down marginally. Figure 1 illustrates this with the 6-month bill, one of the five Treasury securities that are traded weekly. After steady increases in the rates that the Treasury had to pay at auctions in order to sell new debt, the rate is now steady in the vicinity of 5.3%. In fact, the 5.315% rate paid at the auction on October 2nd marks a historic high point; since then, the weekly auctions have sold more debt at marginally lower rates, with the two latest, from October 23rd and 30th, at 5.29%:

Figure 1

The marginal decline in interest on new U.S. debt is visible at all the auctions for weekly debt. It is too early to tell if it will reach the auctions for debt securities sold on a monthly basis, but at this point, it is safe to predict a slow decline in interest rates in the American economy. Except for the usual market fluctuations, it would take a highly disruptive economic event to make interest rates rise any further from where they are now.

The article in the Wall Street Journal is long and gives the impression of being well researched. It is not, but that does not mean the article has no value in the context of predicting the future of the U.S. economy.

It is useful as a case study of how to not do a forecast.