Recently, I explained how Europe abandoned monetary conservatism. This article continues the same review from 2020 through 2023. With that review as a basis, we will also see what 2024 has in store for Europe.

I gave a preview of that outlook earlier this month, noting then that 2024 looks bleak for Europe’s economy. Today’s review reinforces that outlook, especially when it comes to the core of the euro zone. However, I would not rule out that all of the currency area as well as the non-euro EU states will all be in a recession in the second half of next year.

One of the problems is that most countries in the European Union lack the macroeconomic padding that could give them a manageable transition from the economy of 2023 into the recession that awaits next year. That padding, or margin, exists in countries where the economy for a long time has been growing at solid rates of 3% or more per year (Hungary comes to mind). Unfortunately, for most of Europe, and specifically for the euro zone, we are really just witnessing a shift from economic stagnation to a recession.

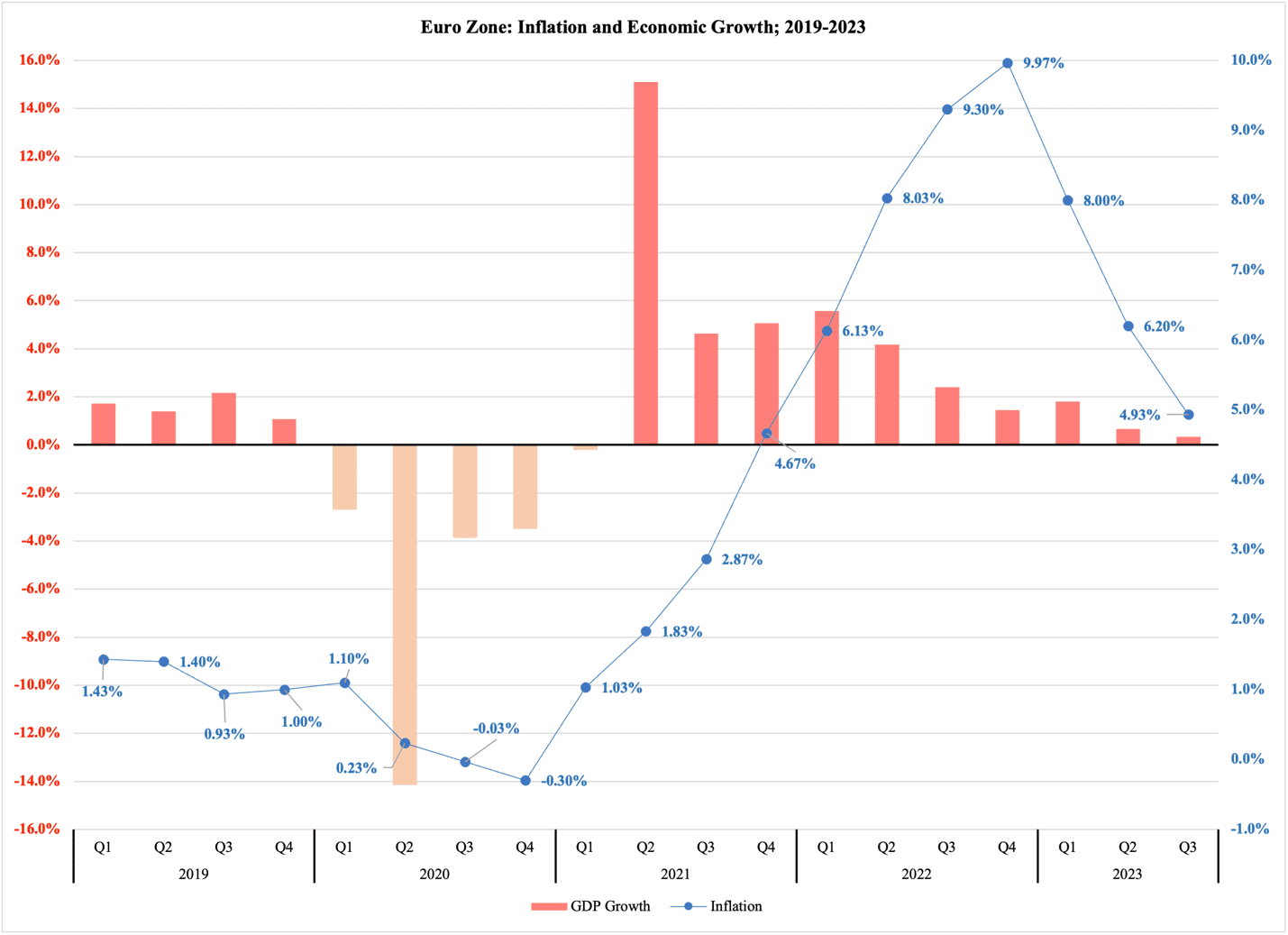

As the red columns in Figure 1 explain, GDP growth over the longer term is barely 2% per year in the euro zone. This was true before the pandemic, and it is true now again with the shockwaves of the pandemic behind us. By early 2022, the euro zone economy returned to its long-term growth path—and to growth rates well below 2% per year.

An economy that cannot maintain at least 2% growth does not produce enough resources for its population to maintain its standard of living over time. I explained this phenomenon of industrial poverty in a book back in 2014, where I also pointed out that this long-term stagnation brings with it chronic problems with government finances. (Ring a bell, Europe?)

The euro zone’s annual GDP growth numbers thus far in 2023 are 1.8% in the first quarter, 0.7% in the second quarter, and 0.34% in the third quarter:

Figure 1

The growth number for the fourth quarter is hopefully not going to be negative; the holiday season always brings out a little bit of extra consumer spending. However, as I explain below with reference to inflation, it could very well be negative. Once 2024 unfolds, the euro zone GDP will shrink for at least the first two quarters of the year.

I have to admit that forecasting the European economy right now is an uneasy experience. Although the numbers do not specifically say so, I still cannot let go of the impression that the economic downturn will be sharp. At present, while everything points to a recession, there is not a single statistic that indicates this recession would open fast and become deep.

At the same time, the ‘facts on the ground’, i.e., the economic data, and the wealth of economic theory behind any forecast, do not always point in the same direction. The body of theory that is political economy contains a wealth of literature on the psychology of human decision-making under uncertain economic circumstances. Those circumstances are often difficult to quantify in measurable terms (especially terms that meet the synthetic standards of rigor in econometric analysis). Therefore, many economists disregard this literature, which is unfortunate.

To ignore theory when doing forecasting is to take enormous risks. If your forecast is used by politicians to make fiscal policy, the consequences can be downright catastrophic.

I mention this only to explain why it is unwise to rely rigorously on quantitative information in economic forecasting.

One of the most important qualitative aspects of people’s behavior is their response to changes in their outlook on the future. When that change goes from optimistic to pessimistic, they react, i.e., change their economic behavior, more quickly than they do when their outlook shifts in the opposite direction.

This means, plainly, that if consumers, business leaders, and investors in general are met with what they deem to be ‘bad enough’ economic indicators in a short enough period of time, they will all shift their economic plans quickly and sizably enough to escalate an otherwise mild recession into a deep and dangerous one.

I am not quite ready to predict a very serious recession for Europe, but there is one variable that points in that direction. Inflation in the euro zone fell briskly during the fall: 4.3% in September, 2.9% in October, and 2.4% in November.

The speed of this inflation decline, which contrasts with the gentle deceleration in U.S. inflation, is in itself a conveyor of information. It is at odds with the predictions by cadres of central-bank econometricians that I recently analyzed, who forecast that inflation will temporarily bump upward in early 2024.

Their forecast has no intelligible context, lest they still believe Europe suffers from monetary inflation. That is not the case: the inflation we now see is of the ‘classic’ kind regulated by the ups and downs in the business cycle. It is important to recognize this because it gives meaning to the rapid decline in the inflation rate: consumers and businesses have shifted into ‘uncertainty mode’ and are in the process of limiting or reducing their economic commitments.

As a result, economic activity is falling fairly quickly here in the fourth quarter of 2023. Based on this mostly theoretical prediction, I would expect a negative GDP number for the fourth quarter.

With that said, there is some good news in the rapidly declining inflation. Even if it only pertains to the euro zone, it is indirectly helpful for the whole of the EU. As inflation returns to the 2% long-term level that the ECB has set as its target rate, there is an increased probability that the central bank will cut interest rates early in the new year.

Very few economists seem to believe that the ECB will execute any rate cuts before the second quarter, and possibly not before June. A month ago, I would have agreed with them. However, if my worries about a rapidly unfolding recession are valid, I can also see the ECB come to the rescue of the economy much sooner than June. If GDP growth is negative from the fourth quarter and on, I would expect an ECB rate cut as early as March.

Will this help the euro zone out of its recession? No. One rate cut will only provide some band-aid for the economy. However, a shift from monetary contraction to an accommodating policy could have a strong enough effect as a confidence booster to at least mitigate the recession.

All in all, 2024 is shaping up to be a tough year for the European economy. Countries outside of the euro zone are well advised not to join the currency area, and to maintain an open mind on what to do, both in terms of fiscal and monetary policy.

More on the non-euro EU states next week. Stay tuned.