According to the Bureau of Labor Statistics, consumer prices in the U.S. economy were 3.1% higher in January than in the same month in 2023. In December, the inflation rate was 3.35%.

Although it is hard to see, inflation is slowly coming down. Back in June, U.S. inflation fell to 2.97%. That was the first time it went below 3% since March 2021, though it ticked up to 3.7% in August and September. It fell again in October (3.24%) and November (3.14%).

When put in this context, the January number is good but not spectacular. Inflation is not easy to get rid of, even as the Federal Reserve has tightened its monetary policy over the past 18 months; it was exactly the right thing to do to put an end to rapid price increases.

With that said, the 3.1% inflation rate for January makes it more difficult for the Federal Reserve to execute an interest-rate reduction as early as March. I explained two weeks ago that emerging indicators of a recession in the U.S. economy would make a rate cut likely as early as next month. Those indicators are still valid, but inflation is the primary variable guiding the Fed’s monetary policy. Therefore, it would have taken a rate below 3% to secure a rate cut on March 19th.

It can still happen, especially if employment numbers for February reinforce the early indicators of a U.S. recession. However, with the January inflation rate slightly above 3%, it will take both a weaker economy and a decisive drop in inflation in February to make the March rate cut happen.

At the same time, the Fed’s Open Market Committee, FOMC, will start cutting rates this spring. It would take a major, upsetting economic event to postpone rate cuts further. I can only see one such event: a fiscal crisis.

Let us save that one for a separate article, later this week. For now, barring a major, negative shock to the U.S. economy, the FOMC will cut its federal funds rate in April. It will be 0.25 percentage points, but if:

then that rate cut could be in the 0.25-0.5 points range.

There is some frustration in the political arena over the Fed’s patience with those rate cuts. Some economists are also voicing concerns about an overly tight monetary policy. This criticism is unwise, especially in the context of how the Fed has handled inflation episodes in the past.

Here is a quick history lesson in three charts, which compare consumer-price inflation to the Federal Reserve’s policy-setting interest rate.

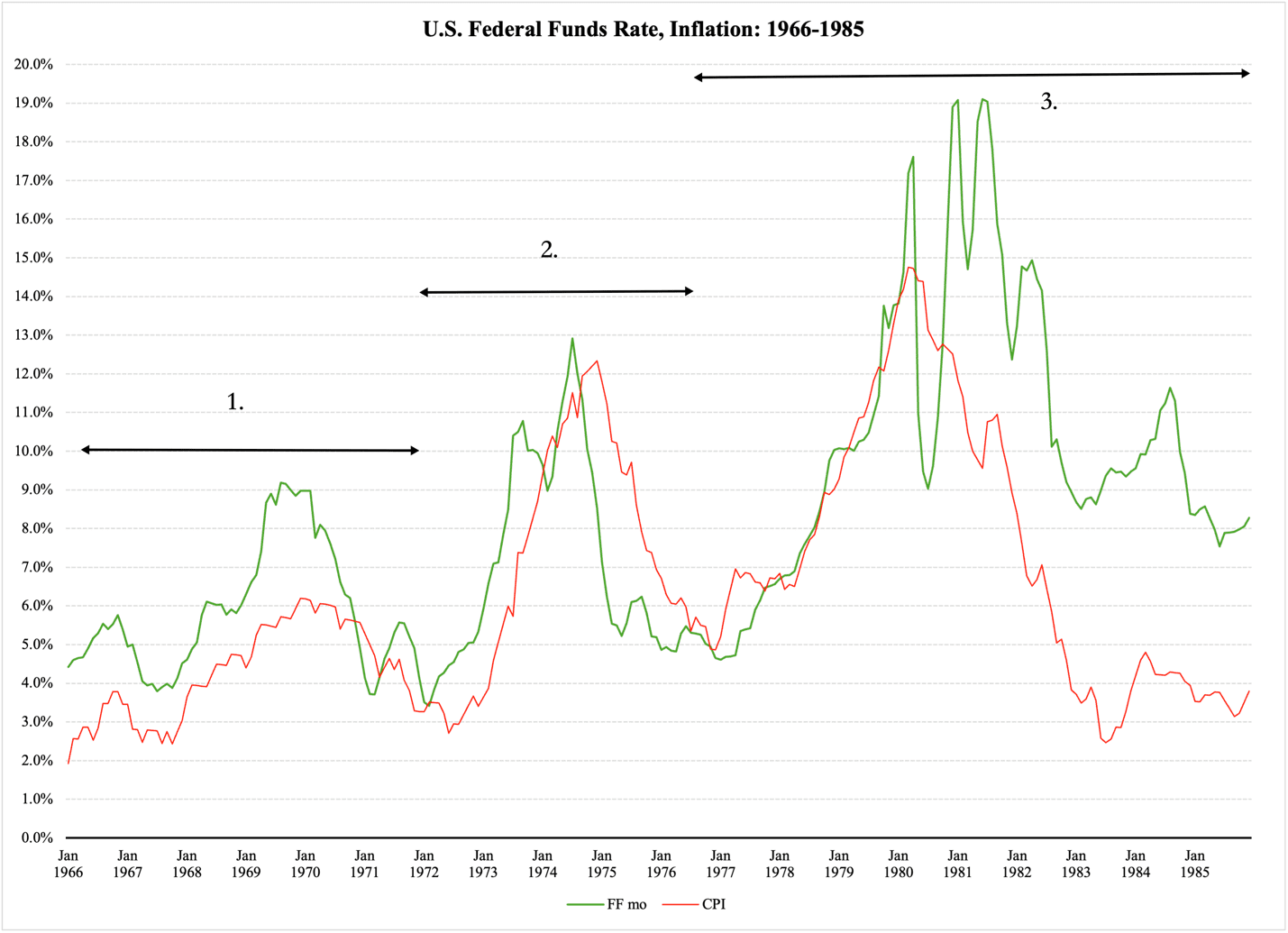

First, the period 1966-1985. This period starts with monetary conservatism (episode 1) in response to rapidly rising prices in 1968. The Fed tightened its money supply and raised the federal funds rate from 4% to 9%. This kept the real interest rate positive at 3%, which—as Figure 1 below explains—was enough to curb inflation. (The green function represents the federal funds rate; the red function represents inflation.)

The inflation of 1968 was related to aggressive increases in government spending; in 1969 the federal government opened up a budget deficit that would last without interruption deep into the 1990s.

The next inflation episode, the second in Figure 1, which began in 1973, had a different origin: it resulted from the oil-price shock when countries in the OPEC (Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) imposed an exports embargo on countries that supported Israel. The oil crisis was exacerbated by the Yom Kippur War in late 1973.

Figure 1

The Federal Reserve took proactive measures in relation to the oil-price inflation shock. This helped curb its impact on the economy. Unfortunately, the Fed lowered its interest rate too rapidly, allowing inflation to get entrenched in the economy; after briefly touching 5% in 1976 it shot up again (episode 3). Global monetary expansion was followed by a second shock in oil prices following the Islamist revolution in Iran.

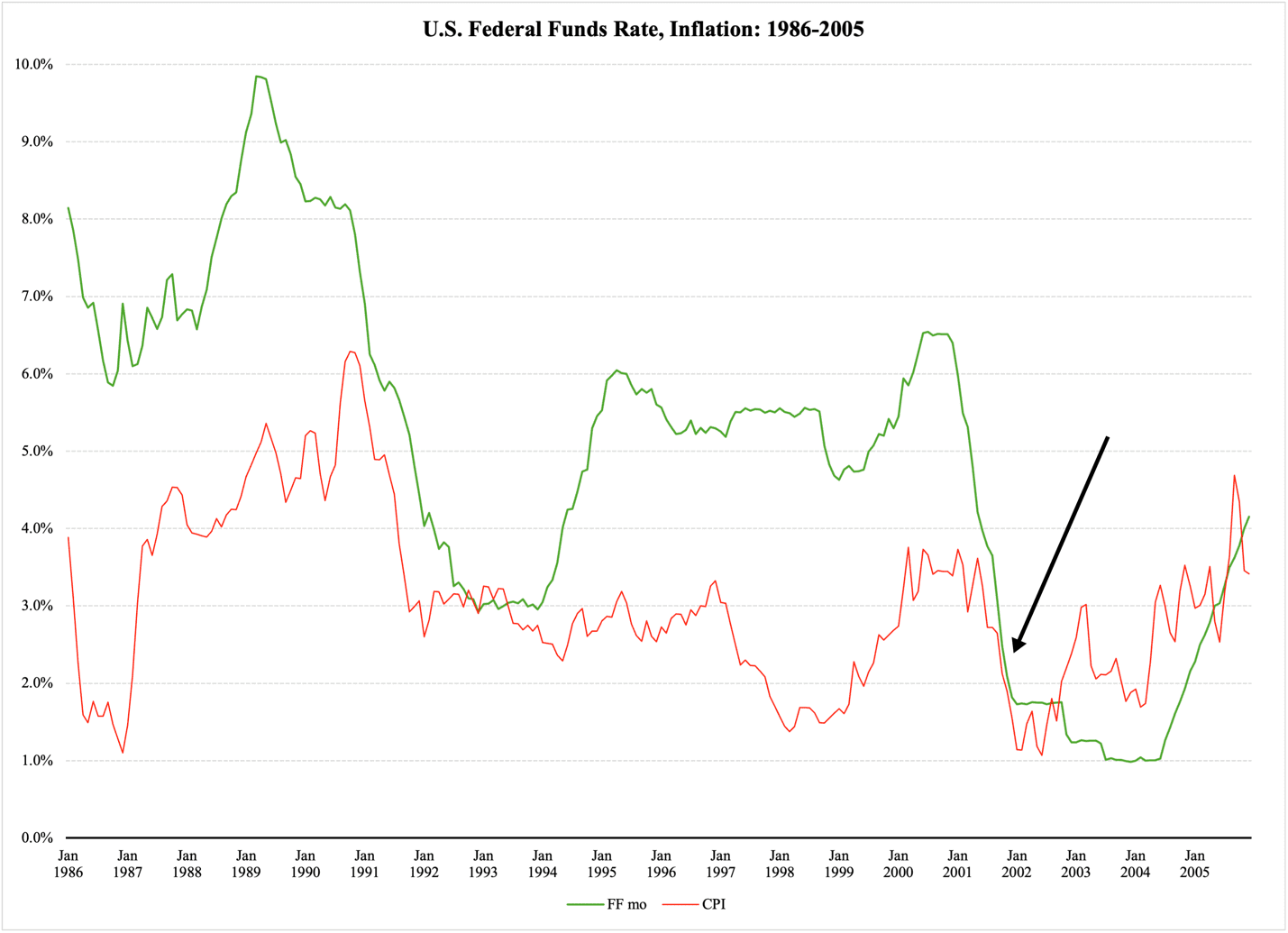

This time, the Fed did not give up so quickly. As Figures 1 and 2 report, the Fed kept its funds rate above 6% almost uninterruptedly throughout the 1980s (please note the scale difference in Figure 2). Inflation slowly fell below 4%, which is remarkable given that the 1980s was a decade of strong economic expansion, not only in America but around the world.

Figure 2

Toward the end of the 1980s, America saw another increase in inflation. This time, it was far from as dramatic as in the preceding decade, but after several years with moderate price increases, inflation rates in the 5-6% range took a toll on the economy. As Figure 2 shows, the Fed responded by sharply raising its funds rate; it stayed above 8% until inflation was clearly subsiding.

The cuts in the funds rate in 1991 and early 1992 were predominantly due to the Fed’s victory over inflation, but they were also motivated by the recession that ended the economic boom of the ’80s.

Once the economy recovered in 1993, the Fed went back to the policy regime it established in the preceding decade: monetary restraint with high real interest rates. This meant, in practice, that it was more lucrative to save money in the bank than to take out a loan. Together with President Clinton’s leadership in bringing the federal government’s budget in balance, these real interest rates helped build strength, resiliency, and financial stability in the American economy.

As a result of the combined fiscal and monetary conservatism, inflation stayed for the most part in the 2-3% bracket. This meant that the only inflation that remained was that which is caused by an economy operating at the maximum of its capacity; logically, when the Millennium recession began in 2001 and the utilization of labor and capital declined, so did inflation.

The Fed responded by cutting its funds rate, but it was forced to do so much more aggressively after the 9/11 terror attacks. The lowering of the funds rate below 2%, and for a time to 1%, did indeed help the economy recover.

Unfortunately, these low rates also created a new problem in the American economy that was unknown in the preceding decades: cheap credit. With inflation taking off while interest rates remained low, the Fed gave up its conservative policy of maintaining a positive real interest rate.

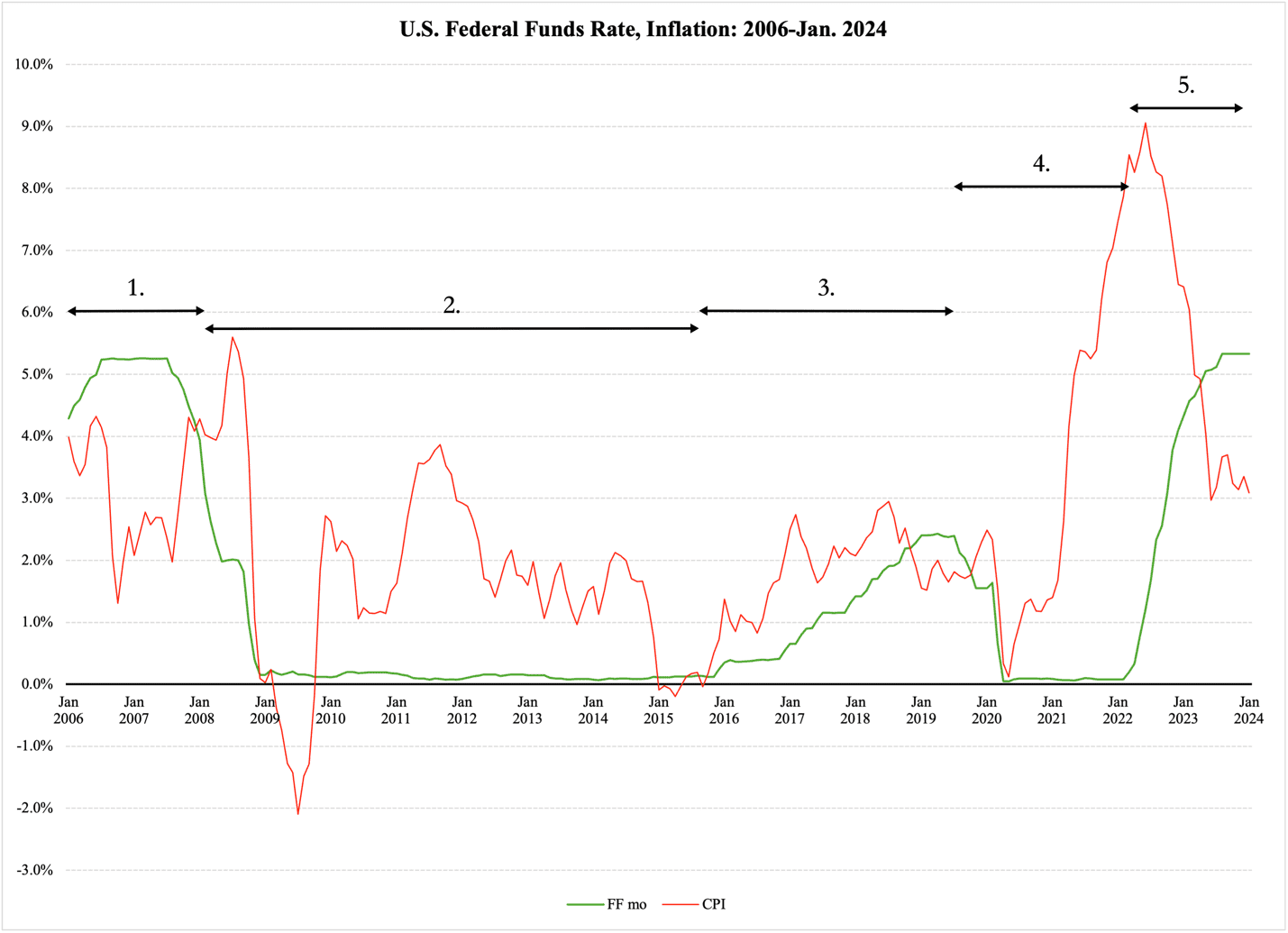

As Figure 3 shows, it was not until 2006 that the central bank regained control over inflation (episode 1). However, its return to a federal funds rate above 5% was short-lived: due to the financial expansion that the Fed had fueled, in late 2008, the U.S. economy plummeted into a new recession.

The Fed responded accordingly:

Figure 3

This time, though, the Federal Reserve did not return to its traditional funds-rate levels (episode 2). The reason was simple: under Ben Bernanke’s chairmanship, the Fed printed tens of billions of dollars every month just to buy government debt.

Inflation stabilized around 2%; in view of the extremely expansionary monetary policy, it is worth asking how this is possible. Shouldn’t inflation have been much higher?

Yes, it should have, but only if real-sector economic activity had been anywhere close to the capacity utilization of the 1990s. Under President Obama (episode 2), workforce participation declined, wage growth stagnated, and for the first time since national accounts were invented, we had a president without a single year of 3% or more in GDP growth.

Thanks only to a largely stagnant U.S. economy, inflation defied the Fed’s irresponsible monetary expansionism. However, as economic activity picked up in the latter half of the 2010s (episode 3), it became clear that inflation was going to shoot up. Thankfully, Janet Yellen replaced Bernanke as Fed head and started reining in the U.S. money supply.

The Trump economy was strong, in some ways as good as or even better than the last four years of the Clinton economy. Again, this would have caused a surge in inflation, had the Fed not moderately raised its funds rate.

Episodes 4 and 5 are familiar: the pandemic with its exorbitant money printing and surge in inflation, and the sharp monetary reversal that ended high inflation. One of the positive outcomes of this reversal is that we are now back to positive interest rates again; if only Congress could move in the direction of fiscal conservatism, the rest of the 2020s might look a little bit like the roaring 1990s.

To get there, though, the people on Capitol Hill need to stop calling for the Fed to rush through interest-rate cuts. They should mind their own business and stop piling up more debt for our kids and grandkids to pay.