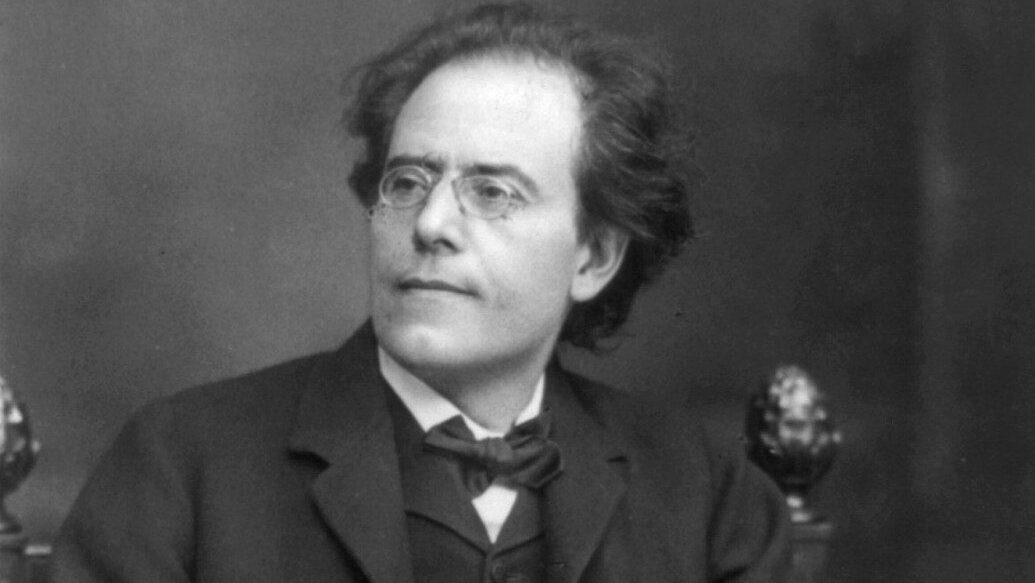

New York City has many troubles, but at least two of its iconic arts institutions, Carnegie Hall and the New York Philharmonic, are squarely back on terra firma. even as others struggle. The contrast is striking. In the same week that saw two massively popular concerts by different orchestras on successive days, each anchored by symphonies from the mammoth oeuvre of Gustav Mahler, the Metropolitan Opera announced another $40 million run on its endowment just to meet operating costs, while the Rubin Museum of Art, which houses perhaps the city’s finest Asian art collection, announced that it will permanently close its doors in October.

What accounts for the difference? In the music world, the explanation could not be clearer. Both Carnegie Hall, which hosts visits and residencies from performers and ensembles, and the New York Philharmonic, a storied orchestra dating back to 1842 which is now thriving in an impressively upgraded concert hall at Lincoln Center, have offered programs of nearly invariable artistic excellence. They have prudently steered away from political controversies, marketed their offerings brilliantly, and kept ticket prices at tolerable levels. Arts managers who have done otherwise should study them carefully.

And what could be more traditional than for both of these successful institutions to program Mahler, absent from the New York scene for some time? Leading the New York Philharmonic was Mahler’s last post before his death in 1911. That same year, Carnegie Hall was the venue for his final concert. In both places, he introduced his music to American audiences, who have loved it ever since.

The Met Orchestra was up first, performing on February 1, the first day of the opera company’s usual month-long winter hiatus. Beginning under its legendary music director James Levine, who built the Met Orchestra into one of the world’s finest orchestras, the opera’s ensemble has been giving concerts of orchestral music in addition to its duties in the house. Levine’s successor, Yannick Nézet-Séguin, chose Mahler’s groundbreaking Fifth Symphony to honor the composer. Well practiced in the high German Romantic school of music, Nézet-Séguin explored the work meticulously and with sonic nuances rarely heard in performance. This is no small feat. Mahler, who suffered emotionally through its composition, described it to his wife Alma on the eve of its premiere in 1904 as “chaos” and a “rushing, roaring, raging sea.”

The work departs from standard symphonic composition, fitting for a time when ‘art for art’s sake’ began to dominate the aesthetics of Western culture. Unlike Mahler’s previous symphonies, there is no real or symbolic literary verse, no narrative idea, other than clashing forces of nature. Clocking in at 75 minutes, its five movements are so sprawling that Mahler felt compelled to arrange them in three distinct parts. The first movement, “Trauermarsch” (“Funeral March”), reflects the composer’s poor health (he had nearly died before starting work on the symphony) and opens with distinctive horns announcing the movement’s “measured pace.” Nézet-Séguin proceeded through this and the subsequent “Stormy” movement, and the third movement scherzo, with balance and grace. The fourth movement, which opens Part III, is an “Adagietto,” a kind of billet-doux that temporarily calms the natural forces. The orchestra proceeded with delicacy, though the contrast strains aesthetic credulity. The Rondo-Finale that ends the symphony returns to the tempestuousness of the work and showcased Nézet-Séguin at his commanding best.

A Mahler symphony normally dominates any program, but the concert featured another hotly anticipated anchor work: the star Norwegian soprano Lise Davidsen singing Richard Wagner’s Wesendonck Lieder. Officially named “Five Poems for Female Voice” and arguably the composer’s best-known work outside of opera, Wagner originally scored the songs for piano to poems by Mathilde Wesendonck, the wife of his admirer and sometime patron Otto Wesendonck, a successful German silk merchant.

Wesendonck supported Wagner during his years of political exile from Germany in the 1850s. For a time, Wagner and his first wife resided in a guest cottage on the Wesendonck estate outside Zürich. There is no conclusive proof that Wagner and Mathilde had an affair, but their closeness cannot be denied and Wagner was hardly a study in sexual restraint. Their infatuation was strong enough for the composer temporarily to abandon work on his epic four-opera Ring of the Nibelung and throw himself into composing Tristan und Isolde, a tale of pure but impossible love.

Art is art, but Wagner’s wife blamed the other woman for breaking up her marriage, and Herr Wesendonck was none too pleased, either. Tristan would be completed in Venice, as the Wagners separated and spun toward their eventual divorce. All that remained were the songs, two of which—“Im Treibhaus” (“In the Greenhouse”) and “Träume” (“Dreams”)—were consciously conceived as “studies for Tristan,” recalling distinctive motifs of Acts III and II of the opera, respectively. Wagner, however, did not oversee the 1862 premiere of the songs, where the pianist was the conductor Hans von Bülow, whom Wagner later cuckolded even as von Bülow led the premiere performances of Tristan. Nor did the composer provide full orchestration for any of the songs except “Träume.” The others were orchestrated by the conductor Felix Mottl in 1893, a decade after Wagner’s death (adding to the legend, just over a month after Mahler died in 1911, Mottl suffered a fatal heart attack while conducting Tristan). Mathilde’s authorship of the poetic texts was not acknowledged until after her death in 1902.

Davidsen has marched through much of the lighter Wagner repertoire, as well as the operas of Richard Strauss, which call for soaring soprano notes. She did not capture the lower-middle range that features most prominently in these songs in the way that Nina Stemme, Waltraud Meier, Jessye Norman, or, (for those fortunate enough to have heard her live) Birgit Nilsson could. Only in “Träume” did the limpid sounds accompanying Wagner’s orchestral hand serve Davidsen truly well. Perhaps ironically, her best singing came in her only encore, the ecstatic “Dich, teure Halle,” Elisabeth’s great aria of expectation from Wagner’s early opera Tannhäuser. Its higher tessitura was a far better fit for her voice, and it is no surprise that Davidsen is the premiere performer of Elisabeth singing today.

The concert began with an eight-minute amuse-bouche by Johann Sebastian Bach, and orchestrated in 1935 by Anton Webern, the “Fuga (Ricercata) a 6 voci,” from Bach’s late-life Musical Offering. Conceived, like The Art of Fugue, as an instructive summary of Bach’s compositional techniques, especially in counterpoint, it was an entertaining diversion but did not fit naturally with the two larger selections.

The concert overlapped with three repetitions of the New York Philharmonic’s Mahler-anchored program, led by National Symphony music director Gianandrea Noseda. Here the symphony was Mahler’s Fourth, a more conventionally programmatic piece evoking the natural surroundings of the composer’s country retreat, where he did most of his work while away from administrative and performing duties in imperial Vienna. The spirit of the symphony arises from the composer’s song cycle Des Knaben Wunderhorn (The Boy’s Wonder Horn), set to folk poems compiled between 1805 and 1808 by the early German Romantics Achim von Arnim and Clemens Brentano, though the text, unlike that used for Mahler’s Second and Third Symphonies, had not appeared in the earlier cycle. The text here, “Das Himmlische Leben” (“Heavenly Life”), presents a child’s view of heaven as related by a soprano soloist. Noseda led a bravura performance, with every part of the orchestra resonating with crystal clarity in the recently renovated concert hall. Golda Schultz gave pleasant, if not incisive, rendition of the solo part, much as she did with the introductory selection, Mozart’s “Ch’io mi scordi di te?,” a standalone aria dramatizing the insecurities of love.

The rest of the program was devoted to the superb young Swiss pianist Francesco Piemontesi’s playing of Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 25, in his debut performances with the New York Philharmonic. At his delicate hands, one could easily forget that Mozart’s prolific works in the piano concerto form were mainly conceived early in his career as one-off entertainments for patrons. By the time he wrote his twenty-fifth work in the genre, when he was older and more successful, they had become both more infrequent and longer lasting. Composed in 1786, No. 25 was the last of the composer’s “twelve great piano concertos,” though he later wrote two more that are less performed. A recognized masterpiece of the form, it contains music foreshadowing themes from Mozart’s opera The Magic Flute. There is also some similarity to the French revolutionary anthem La Marseillaise, though this is almost certainly coincidental as the song was not composed until five years later.

Piemontesi played a shimmering performance with technical faultlessness and a superb synergy with the orchestra under Noseda. His playing’s lightness was a fine balance to the Mahler Fourth, but fans of heavy symphonies will not be disappointed in New York this season. The Munich Philharmonic offered all-Brahms programs in the days following the performances under review here, while the Vienna Philharmonic’s March residency—at Carnegie Hall and later in West Palm Beach, Florida—will feature the Ninth Symphonies of both Mahler and Anton Bruckner. In between, the Orchestra of St. Luke’s will play Carnegie with Mozart’s 40th Symphony, while Noseda will appear there with the National Symphony in a concert featuring Beethoven’s Third.