The euro was going to give Europe monetary policy clout on par with the United States. At the time of its minting, proponents of the euro suggested that it might even replace the dollar as the world’s reserve currency.

While such wild predictions were a bit outlandish even in the most euro-phoric times around the turn of the millennium, there was broad consensus among economists and politicians alike that the euro was going to make Europe economically stronger—and more independent.

We now have nearly a quarter of a century of records showing that this did not happen. If anything, the euro zone is more dependent on the American Federal Reserve for its monetary policy than any single pre-euro European country was.

It is with this experience in mind that we address the question: will interest come down, especially in Europe?

Ironically, the answer shows the benefits for a country that maintains its national currency—and the detriments for those who join the euro.

To see how this is possible, let us go back to May 1st, when the Federal Reserve announced that it would keep its policy-setting federal funds rate—technically its target range—unchanged for the time being. Noting the strength of the U.S. economy, the central bank’s policy-making Federal Open Market Committee, FOMC, also explained that inflation, while having come down in the past year, remains too high for the FOMC’s comfort.

They also made this important statement:

The Committee does not expect it will be appropriate to reduce the target range [of the funds rate] until it has gained greater confidence that inflation is moving sustainably toward 2 percent.

Before we examine the close correlation between the Fed’s interest-rate decisions and those made by the European Central Bank, let us take a look at Hungary, one of the seven EU members who have not yet joined the euro. The Hungarian National Bank is possibly the most proactive in Europe, using the full range of its currency independence to benefit the Hungarian economy.

Since October last year, the Hungarian national bank has been lowering its base rate in multiple steps, from 13% to the 7.75% it decided on as recently as April 24th. These rate cuts came on the heels of Hungary’s tough encounter with inflation: for a short period of time, the country had the highest inflation rate in Europe.

Thanks to its National Bank’s active but prudent monetary policy, Hungarian inflation has come down as rapidly as it increased. The National Bank responded early to inflation and is now reaping the benefits of being able to lower interest rates—when others are not.

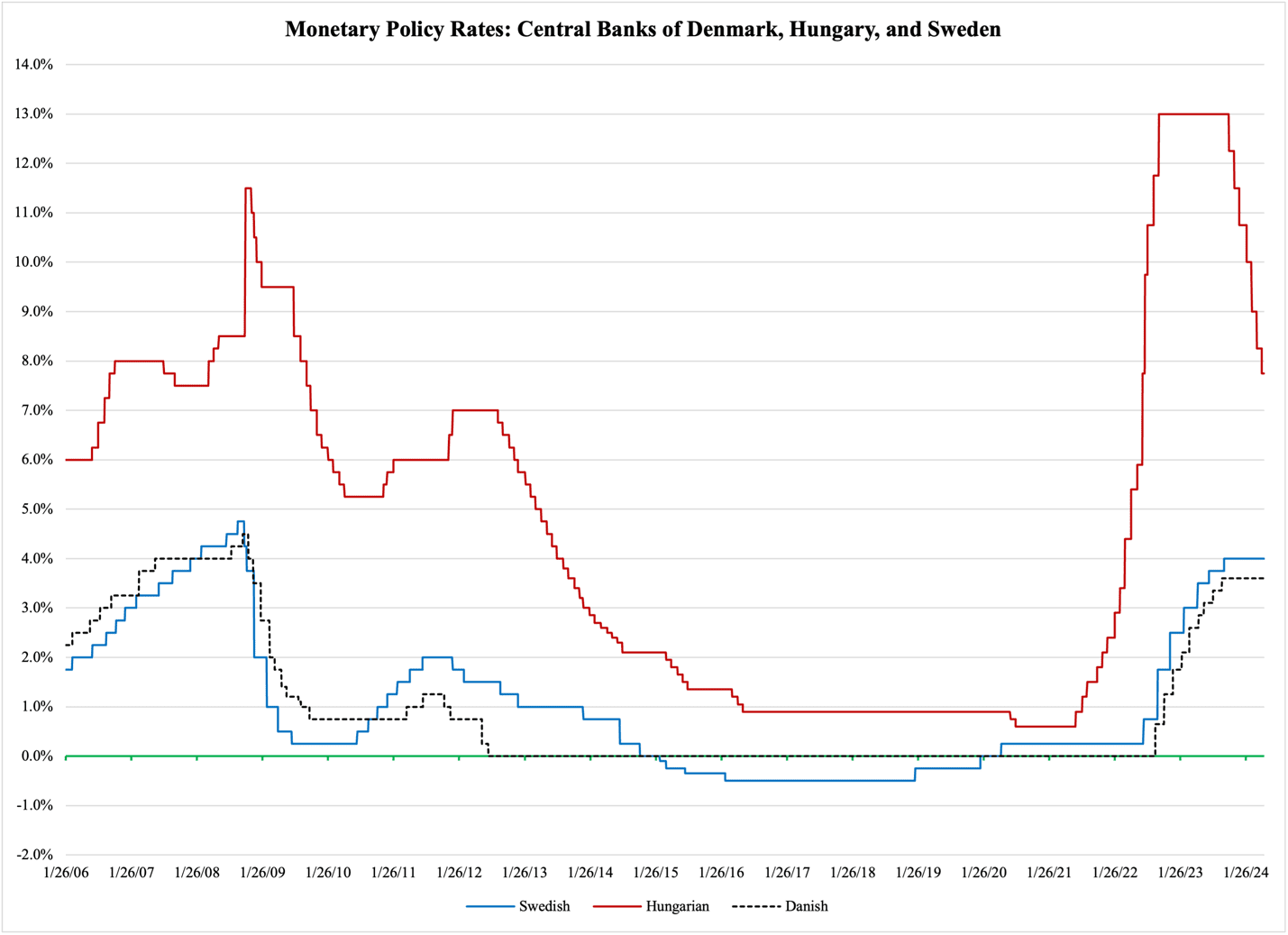

To take one example, as Figure 1 shows, the Swedish Riksbank was late on the ball raising its policy interest rate. This means that, unlike Hungary, it cannot yet lower its rates—a fate it shares with the Danish National Bank:

Figure 1

In fairness, Hungary had much higher inflation to deal with than Sweden and Denmark did, but it also had a more strongly growing economy. The Hungarian National Bank did not want its country to lose that growth momentum, which is why it intervened early in the inflation episode. Thanks to its successful measures, it can now lower its interest rate while others cannot.

I do not expect the Riksbank to announce a rate cut on May 8th. If they do, it will raise the inevitable question of whether Sweden is on a fast track to euro membership.

It would be unfortunate if the Riksbank precipitated a euro accession by lowering interest rates prematurely. Unlike the Hungarian bank, the Riksbank has not yet built a credible policy room for lower rates; while Budapest defeated inflation early on, Stockholm has not yet entered the final battle.

The contrast between Hungary on the one hand and Denmark and Sweden on the other has a lesson for both euro zone and non-euro EU states. Although interest rates are still considerably higher in Hungary than in the two Scandinavian countries, they are coming down, briskly and predictably. This sends a signal to foreign investors that the National Bank is defeating inflation, and that Hungary has a resilient economy spearheaded by a proactive monetary authority. As Europe falls deeper into the recession, these signals of intelligent policymaking will give Hungary an important edge in a European economy where the overall economic trend is negative.

As Hungary has often demonstrated, having your own currency gives you considerable latitude, even as global trends affect interest rates in individual countries. In Figure 1, e.g., there were ups and downs in international interest rates in the years prior to and during the Great Recession of 2009-2011. Those were volatile times for interest rates, in part because the euro was relatively new and the dollar was undergoing an interest rate depression of a kind the world had not seen before.

Due to those volatilities, the economies of individual countries were often one small step from hard times; with individual currencies, their central banks could fine-tune interest rates, exchange rates, and the balance of financial payments. Done right, this mitigates a country’s macroeconomic risks and exposure to global shocks.

After the Great Recession, central banks got more room to be proactive policy setters. Hungary, with a different economic background than, e.g., Sweden and Denmark, could chart a course to lower interest rates that suited the central bank’s concern for inflation—which was almost eradicated at the end of the 2010s—while assisting in the furtherance of other economic policy goals, including the Hungarian government’s gradual pursuit of fiscal balance and high, sustained levels of GDP growth.

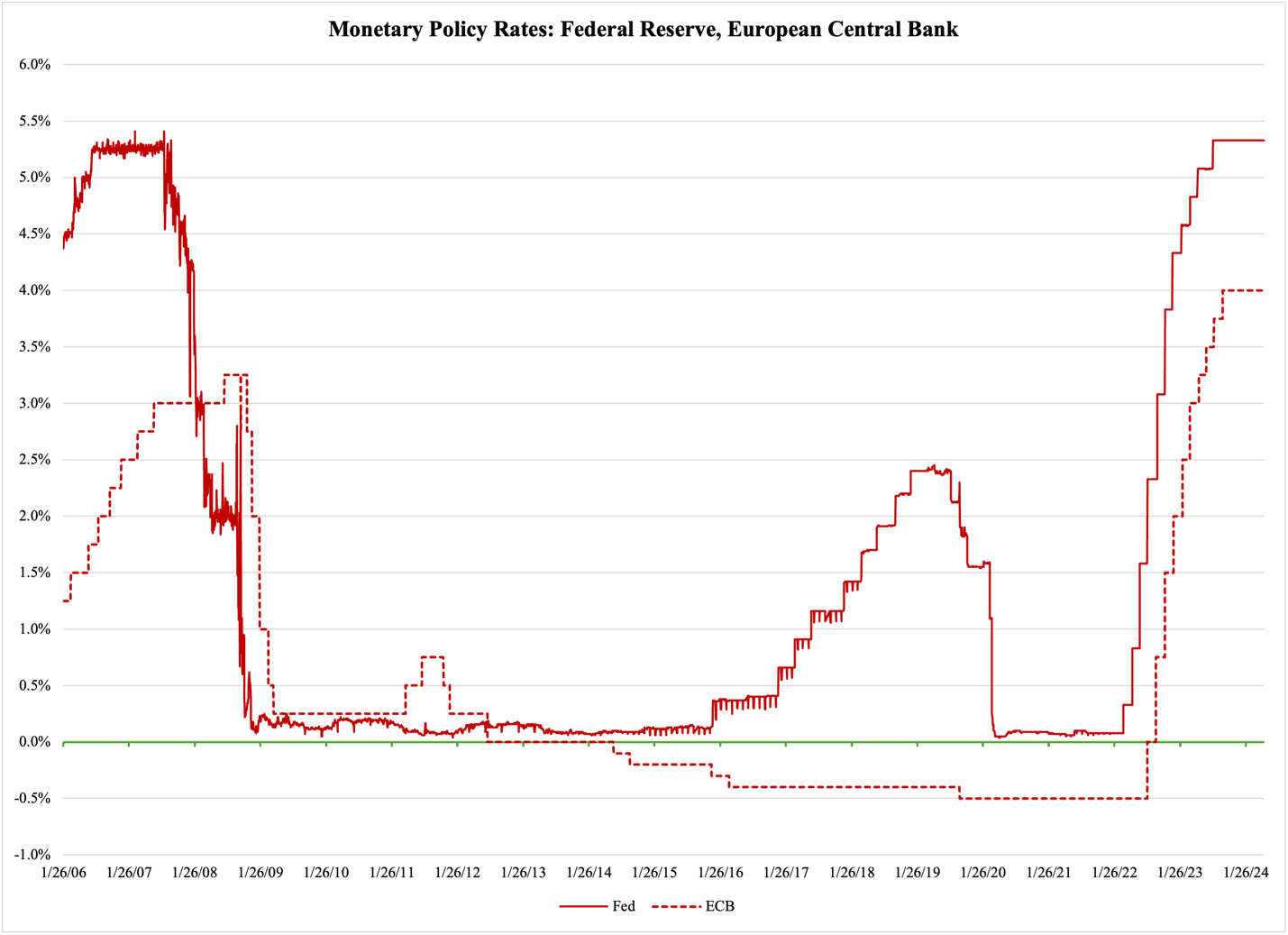

If Figure 1 shows the advantages of maintaining a national currency, Figure 2 explains how joining the euro zone can become a national boondoggle. The policymaking interest rates in the euro zone correlate closely with the Federal Reserve’s funds rate; with one exception—the partial monetary tightening when Janet Yellen ran the Fed—the correlation is so close that we can effectively conclude who really sets the ECB’s interest rates:

Figure 2

The ECB’s rate-setting pattern, with its close tie to the Federal Reserve’s lead, means that any EU member state that joins the euro zone will lose the latitude in policymaking demonstrated by the Hungarian National Bank, and instead be inextricably tied to American monetary policy.