In two press releases this week, the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics crushed the hopes that inflation would soon be returning to 2% here in America. The first press release announced that inflation in producer prices has bounced back into positive territory: after being negative—technically known as deflation—from March last year through March this year, in April producer prices increased by 0.13% on an annual basis.

The following day came the press release about consumer price inflation, which was 3.36% in April.

Neither number is good, but there is also not much negative information in these numbers either. Inflation in consumer prices is not falling, but it is also not rising. The April number confirms a trend averaging 3.3% in annual inflation that became visible in October last year. Although a slight upward bounce in producer price inflation is unfortunate, it is also a piece of news not to be taken too dramatically.

The bigger question here, which nobody seems to want to discuss, is why inflation stabilizes at this somewhat elevated level. Everything else about this inflation episode is clear and simple: it was caused by the excessive monetary expansion of 2020 and 2021; as soon as the Federal Reserve reversed course and began shrinking the money supply, inflation rapidly subsided.

Why would inflation not return to the long-term stable level where it was prior to 2021?

To answer this question, we need to take a step back and spend some time admiring the free market. This wonderful invention is a superior mechanism for bringing buyers and sellers together, for distributing goods and services from those who produce them to those who want them. Writ large, the free market gives everyone a chance and inherently does not discriminate against anybody.

In a manner of speaking, the free market is the most successful meritocracy mankind has ever invented.

However, for the past century, we have thrown a great deal of doubt at the free market. To be fair, some of it has been merited, especially when big businesses try to manipulate the market to their favor. But once our governments obtained—or in some cases usurped—the power to regulate markets, we have slowly lost some of the benefits that come with a market-based economic system.

One of the many losses that come with growing government encroachment on the free market is a weaker ability of the economy to absorb inflation. Under the free market, inflationary episodes are mitigated and ended by resilient competition, by entrepreneurs innovating new, more efficient ways to produce, and by households adjusting their workforce participation and their spending habits.

In a theoretical economy with a completely free economy, inflation episodes are short, mild, few, and far between. When we reduce the free market realm and replace it with taxes, regulations, and government spending, we also reduce the realm of the economy that can make the necessary adjustments to bring inflation to an end.

Government is by definition not dynamic, not competitive, and not innovative. As its spending, its regulatory authority, and its taxes occupy a growing share of the economy, inflation becomes a more persistent problem. This helps explain why, over the past 100 years, persistent inflation episodes have taken place since government spending exceeded 30% of GDP. The U.S. economy passed this threshold in 1970; in the decade that followed, the U.S. economy endured two substantial inflation episodes.

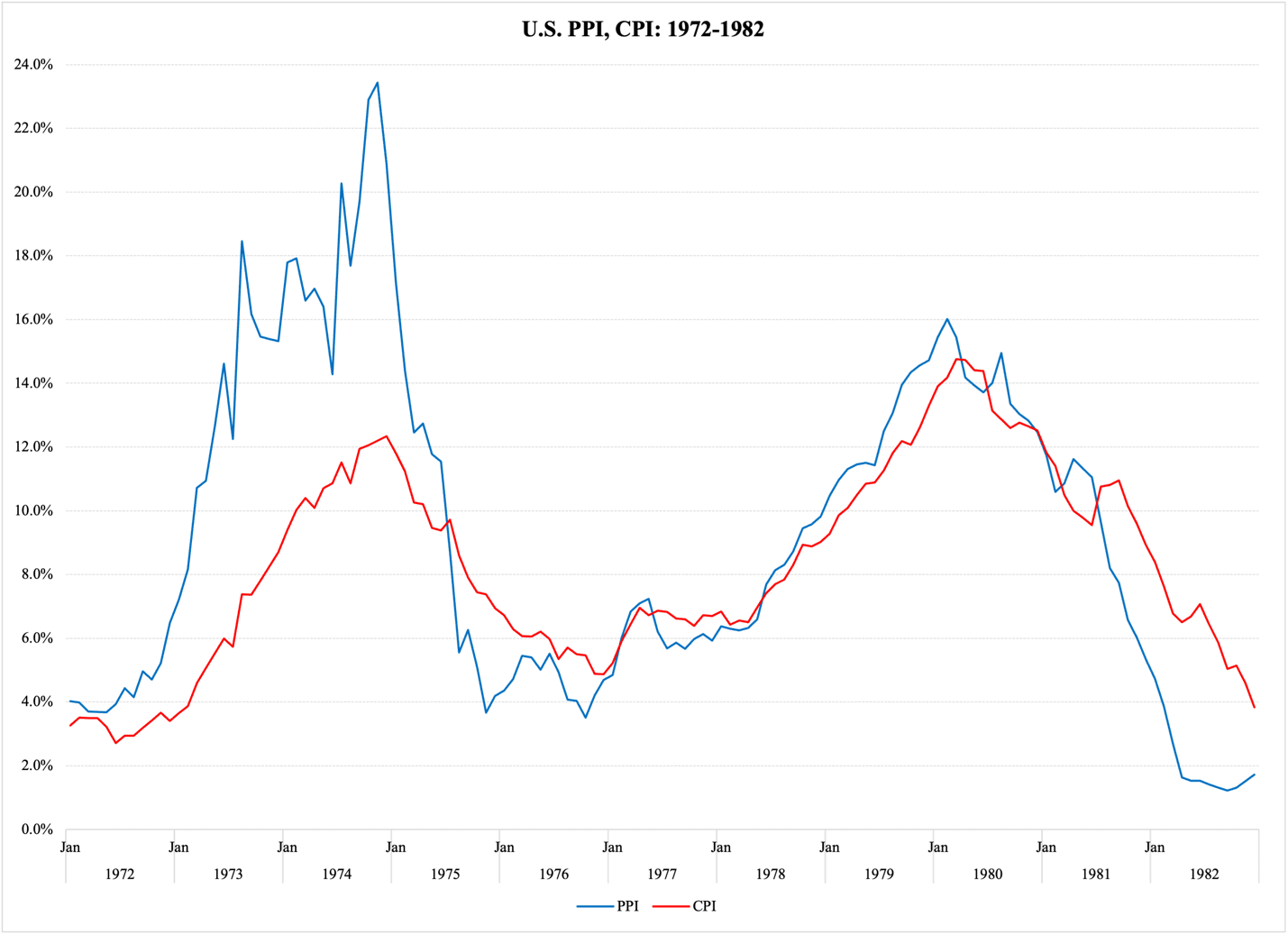

Figure 1 reports these episodes, comparing producer (PPI) and consumer (CPI) inflation:

Figure 1

Political events—government writ large—caused a supply-side shock to the world economy in the early 1970s. Producer prices spiked and gradually pulled consumer prices up as well; as a general statistical rule, there is a two-month lag from the former to the latter. Upon the ending of the oil crisis in the Middle East—i.e., the political fuel that caused inflation—producer price inflation declined rapidly.

Unfortunately, a second oil crisis erupted in 1979, but there was also an element of monetary inflation fueling price hikes in the late 1970s. Hence, the second inflation episode of that decade. In both those episodes, consumer prices followed producer prices at a relatively brisk pace. This was, again, attributable to the relative size of the free market in the U.S. economy.

It is worth noting that inflation did not immediately fall to the levels cherished by central banks today; it was not until 1986 that inflation dropped below 2%. When it did, though, under the regime of a monetarily conservative Federal Reserve, U.S. inflation had only a couple of encounters with the 5% threshold.

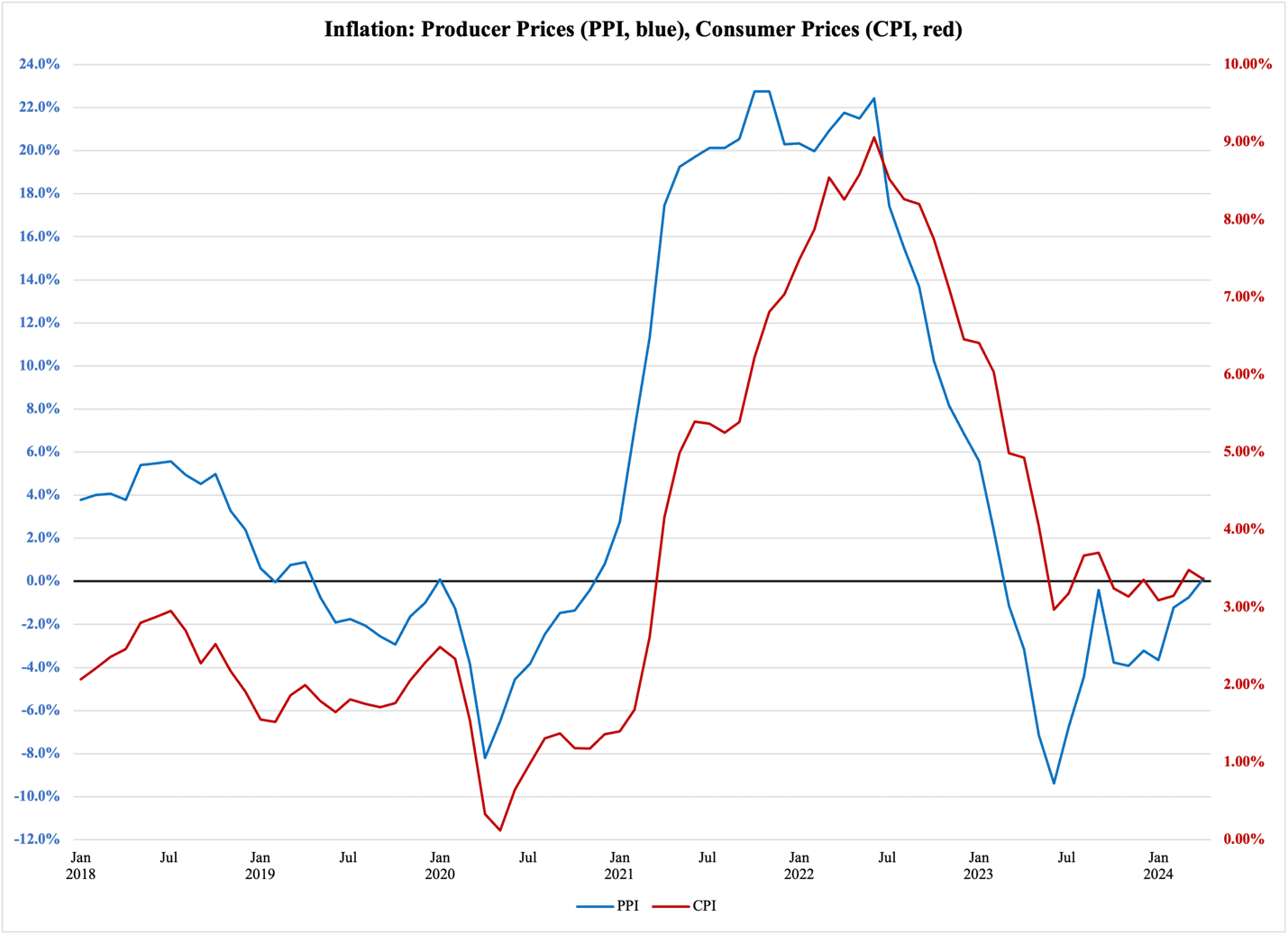

That changed in 2021. Driven by a massive monetary expansion, producer prices inflated rapidly and pulled consumer prices with them. The rapid and at least initially destabilizing rise in prices sent a shockwave through an economy that had almost no institutional memory of high inflation.

One characteristic of our recent ‘pandemic inflation’ episode, which it does not share with its ‘oil price inflation’ predecessor, is that producer price inflation rose considerably higher than consumer price inflation did. In Figure 2, the two inflation trends are measured on different scales in order to illustrate the close correlation between PPI and CPI; it is essential to note that the CPI peak lies at not even half the level of PPI:

Figure 2

There are two reasons for this difference: bigger government spending and more intrusive regulations. Government has increased its space in the economy, with total federal, state, and local public outlays accounting for 37.3% of GDP in 2022 and 2023. This compares to 26.7% in the 1960s; the free market lost 10.6 percentage points of the U.S. economy.

Regulations have also expanded over the past half-century, making it administratively more expensive and burdensome to do business. The economy becomes less adaptive, less dynamic, and less prone to innovations.

As a result, the ability of the economy to absorb and eliminate inflation is now probably weaker than it has been in recorded economic history. As mentioned, we see this in the inflation statistics: although inflation came down rapidly, consumer prices have refused to fall below a trend of approximately 3.3% per year.