Recent news about China selling U.S. debt stoked fear in some parts of the internet, with rising worries about an organized flight from the dollar by the countries in the BRICS group. As I explained on Tuesday, the Chinese sell-off was nowhere near enough to cause any disturbances in the U.S. debt market, nor was it intended to do that.

Nevertheless, it is a fact that the dollar is slowly dwindling as a central bank reserve currency. It is also a fact that the BRICS group, which is a growing formation of dollar-skeptic nations, is developing a new framework for trade that is independent of the dollar. Therefore, we can safely predict that, at some point in the future, there will be turmoil in the market for U.S. government debt.

Today, there are no signs of such turmoil, but the market continues to send subtle signals that its confidence in the U.S. government is wearing thin. These signals are embedded in the inverted yield curve and the so-called tender-accept ratio.

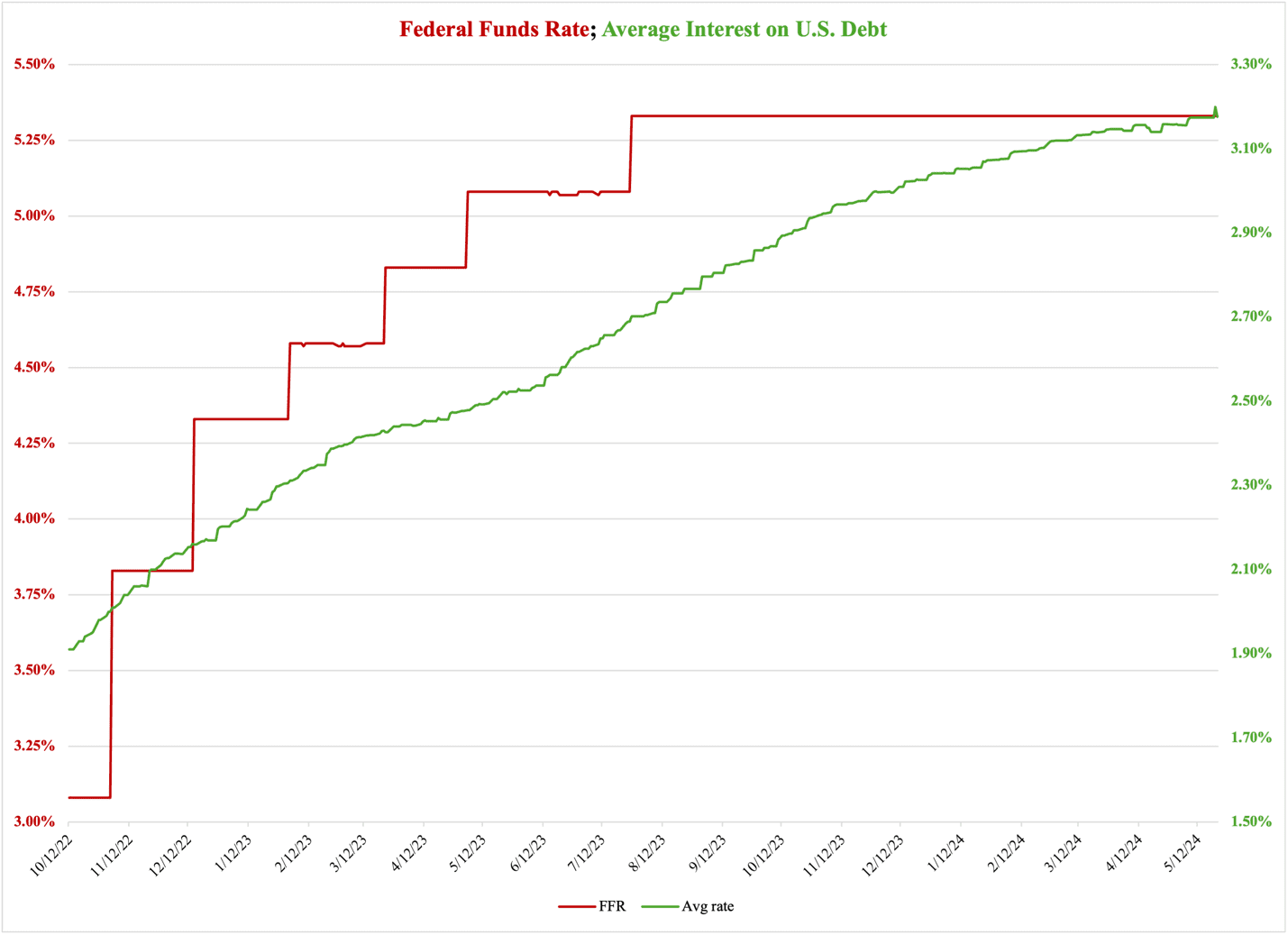

To start with the inverted yield curve, its definition is that interest rates—yields—are higher on short-term Treasury securities than on those with longer maturity. To some degree, it is the product of the Federal Reserve increasing its policy-setting federal funds rate. As Figure 1 shows, the increases in this rate (red function) correlate closely with the rise in the average interest rate on U.S. debt (green):

Figure 1

However, not all of the interest-rate hikes are attributable to the Fed’s tightening of money supply. The inverted yield curve—see Figure 2 below—came about as a response to high inflation in late 2022; the level of interest rates on short-term debt reflected the rise in the federal funds rate. Long-term rates remained lower because investors expected inflation to be a temporary phenomenon.

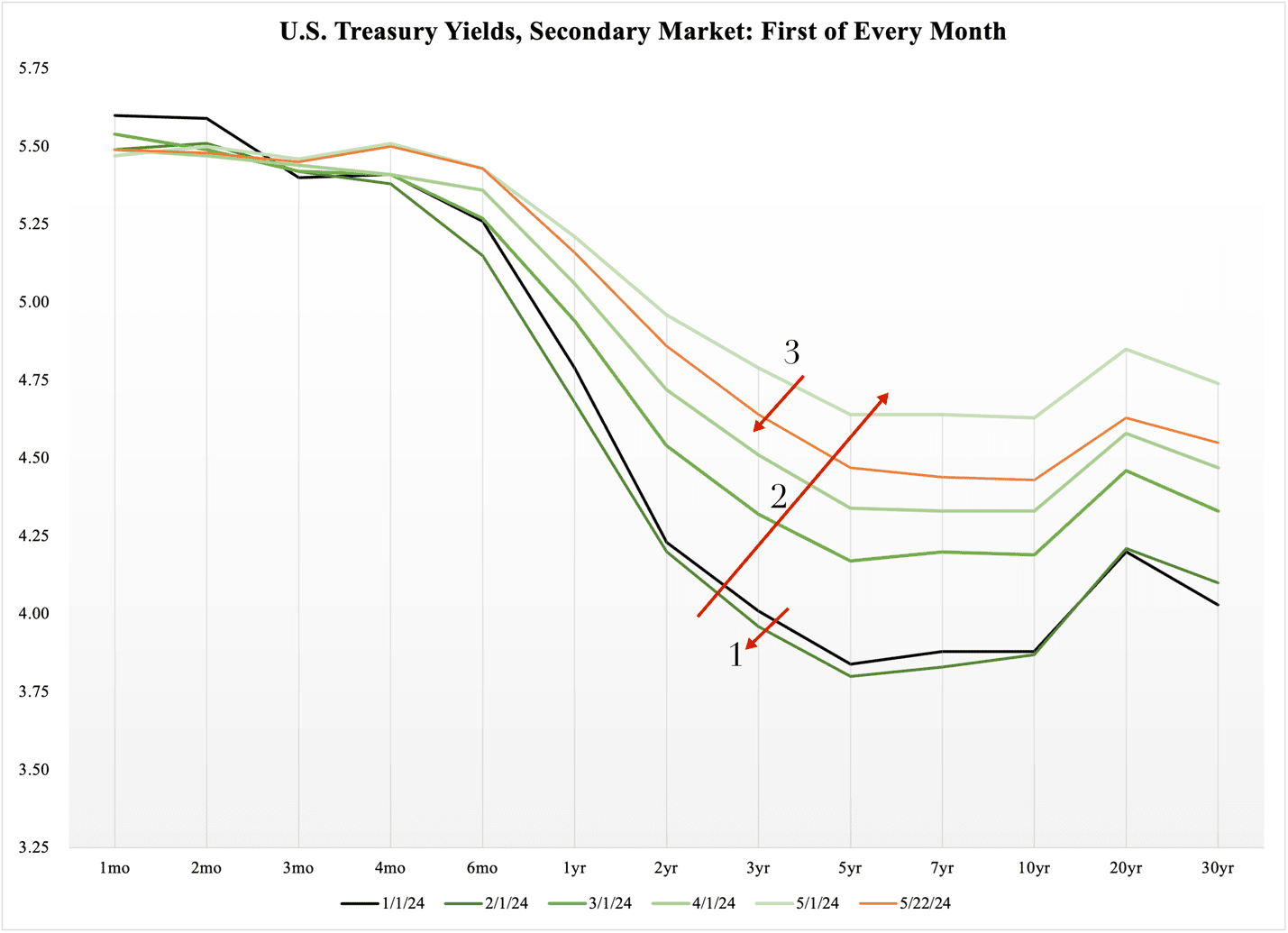

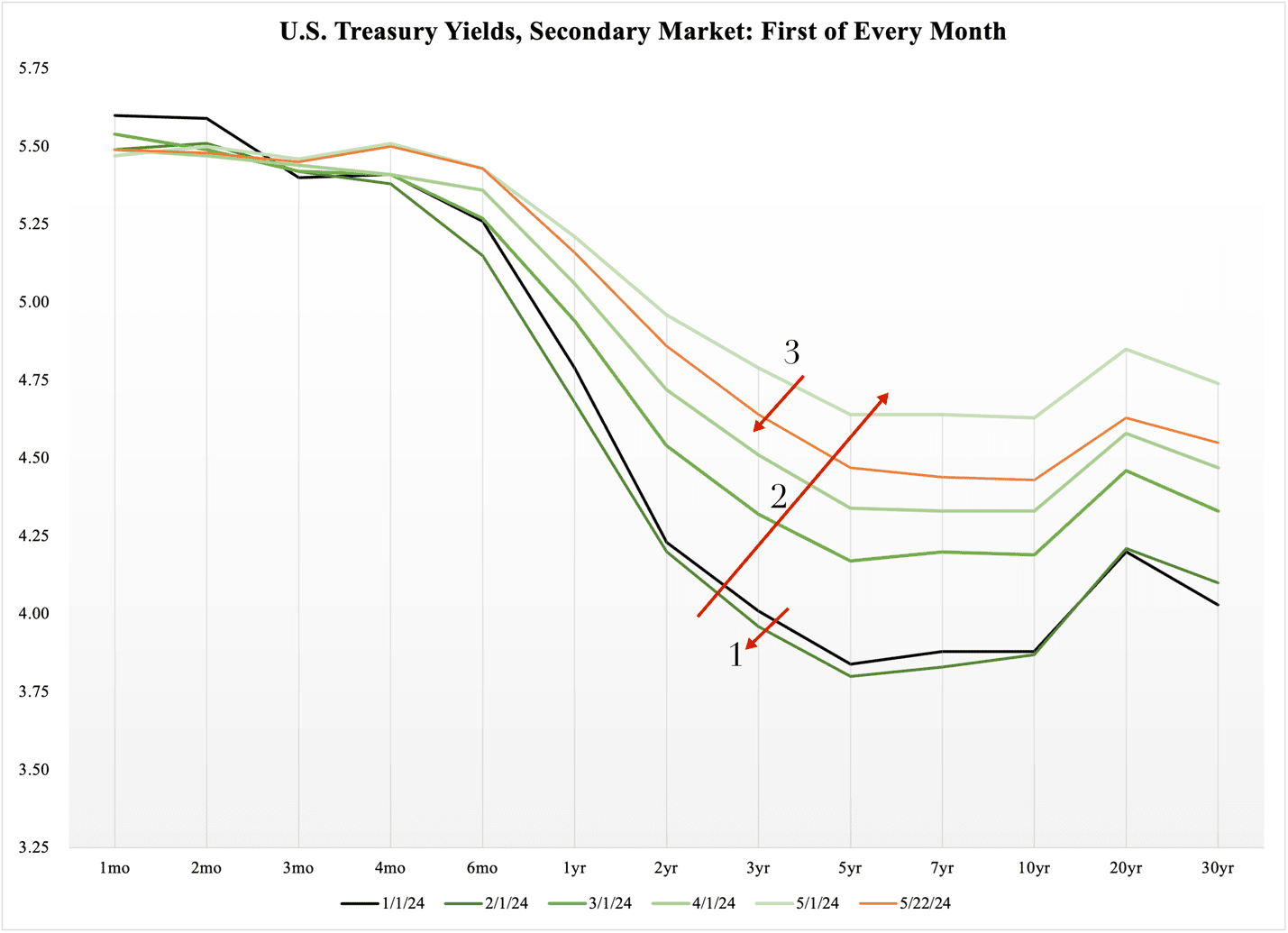

Well, here we are, with the peak of inflation far behind us, and the yield curve is still inverted. To make matters worse, as Figure 2 shows, there has been an upward pressure on the yields of long-term debt. After a small decline in long-term rates from January to February (Arrow 1) those rates increased steadily through the end of April (2). They have fallen modestly in May (3) but show no signs of returning to the low levels of early this year or last year.

Figure 2

The rise in long-term yields is countered by a drop in the values of the debt securities themselves—in other words, a price cut. When the prices of U.S. debt securities fall, the reason is always greater supply than demand.

In short: for the better part of this year, investors in general have reduced their holdings of U.S. debt relative to the supply of that same debt. It does not mean that investors are leaving the market per se—as is evident from data supplied by the Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the daily volumes traded on the markets for U.S. debt have actually gone up since the beginning of the year. However, investors are uneasy and prefer to stay liquid; one of the least traded U.S. debt securities is the 20-year bond. Its monthly auctions sell about $17 billion, while the weekly auctions of the 4-week bill sell some $80 billion.

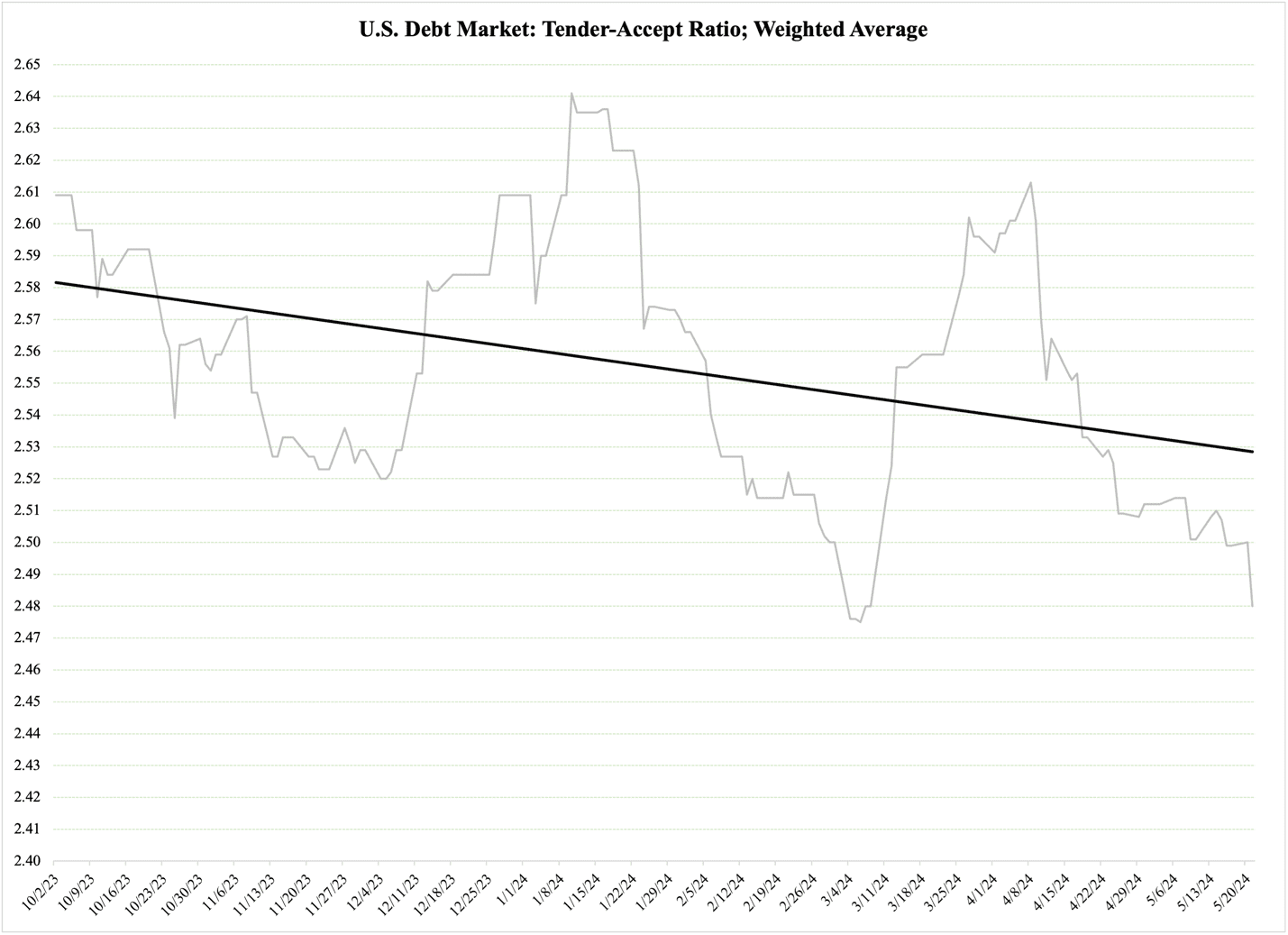

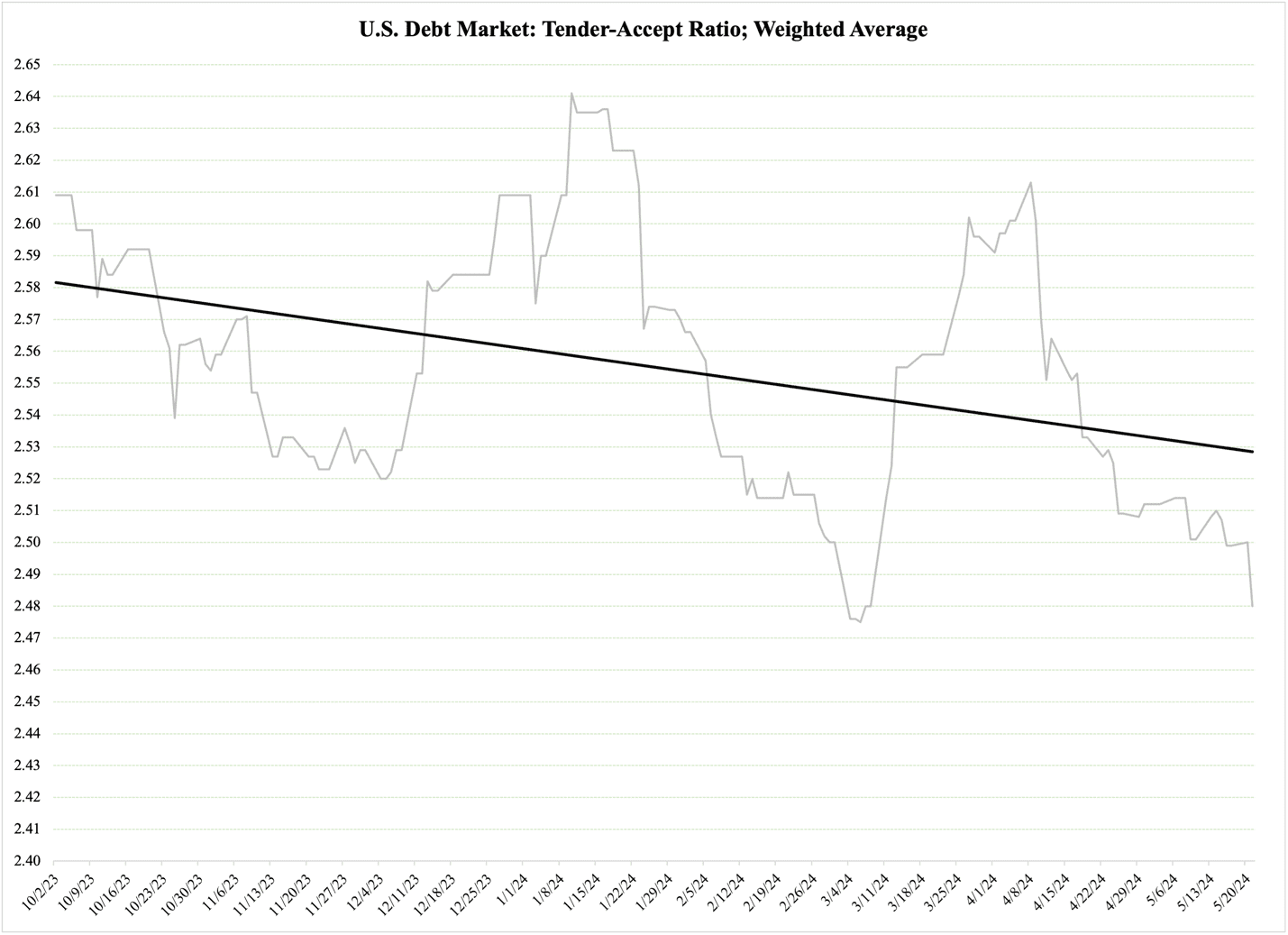

While investors exhibit their somewhat muted worries about the U.S. debt market, they are also slowly becoming more cautious in general as to buying U.S. debt. This is shown in the so-called tender-accept ratio, i.e.,

- The ratio between the money that investors put up as tender offers to buy debt and

- The amount of debt that the U.S. Treasury wants to sell at any given auction of new debt.

The T/A ratio is an almost universally overlooked control variable for the mood of the market for sovereign debt. That is regrettable, because as Figure 3 shows (with a weighted T/A for the entire U.S. debt), this ratio has been declining at the debt auctions since at least early October. Although there are significant swings in the variable, the trend is steadily downward:

Figure 3

The yield curve and the T/A ratio work well together as indicators of overall investor strategy. They are not screaming investor flight—not even close—but they are telling us that investors are close to their saturation point, i.e., where they can no longer motivate buying more U.S. debt based on their investment portfolio strategies.

If there is one thing the U.S. debt market does not need right now, it is a major sell-off by a foreign investor like the Chinese government. Their sale in the first quarter this year was not dramatic enough to cause a stir in the market, but should they return with a bigger, more concentrated sale, and dump tens of billions of U.S. debt in a week or two, then there would be chills going down the spines of many people on the sovereign-debt market.

At that point, anything will be possible. And as always, Congress can put an end to this crawling erosion of confidence in the debt market. All they have to do is unite around a consistent, coherent, and intelligent plan to rein in the federal government’s $2 trillion budget deficit.