On May 30th, the U.S. Bureau of Economic Analysis, BEA, released the final piece of data on the federal government’s spending and revenue in the first quarter of this year.

As always when these releases happen, it is a fiscal horror story. However, the worst part of it is that nobody seems to care anymore.

I care, and you should, too. It does not matter if we live in America or not—the fiscal status of the United States government has become a global matter. When America falls into a debt crisis, the ramifications will be hard, swift, and serious throughout the global economy.

The BEA’s latest numbers confirm what I pointed to as recently as on Wednesday: the federal government’s debt is a fiscal powder keg that can explode at any time.

According to Table 8.3 under the national accounts section in the BEA database, the U.S. government earned $1,293 billion in revenue in the first quarter. Its spending amounted to $1,646 billion, for a deficit of $354 billion. This means that the deficit paid for 21.5% of all federal spending.

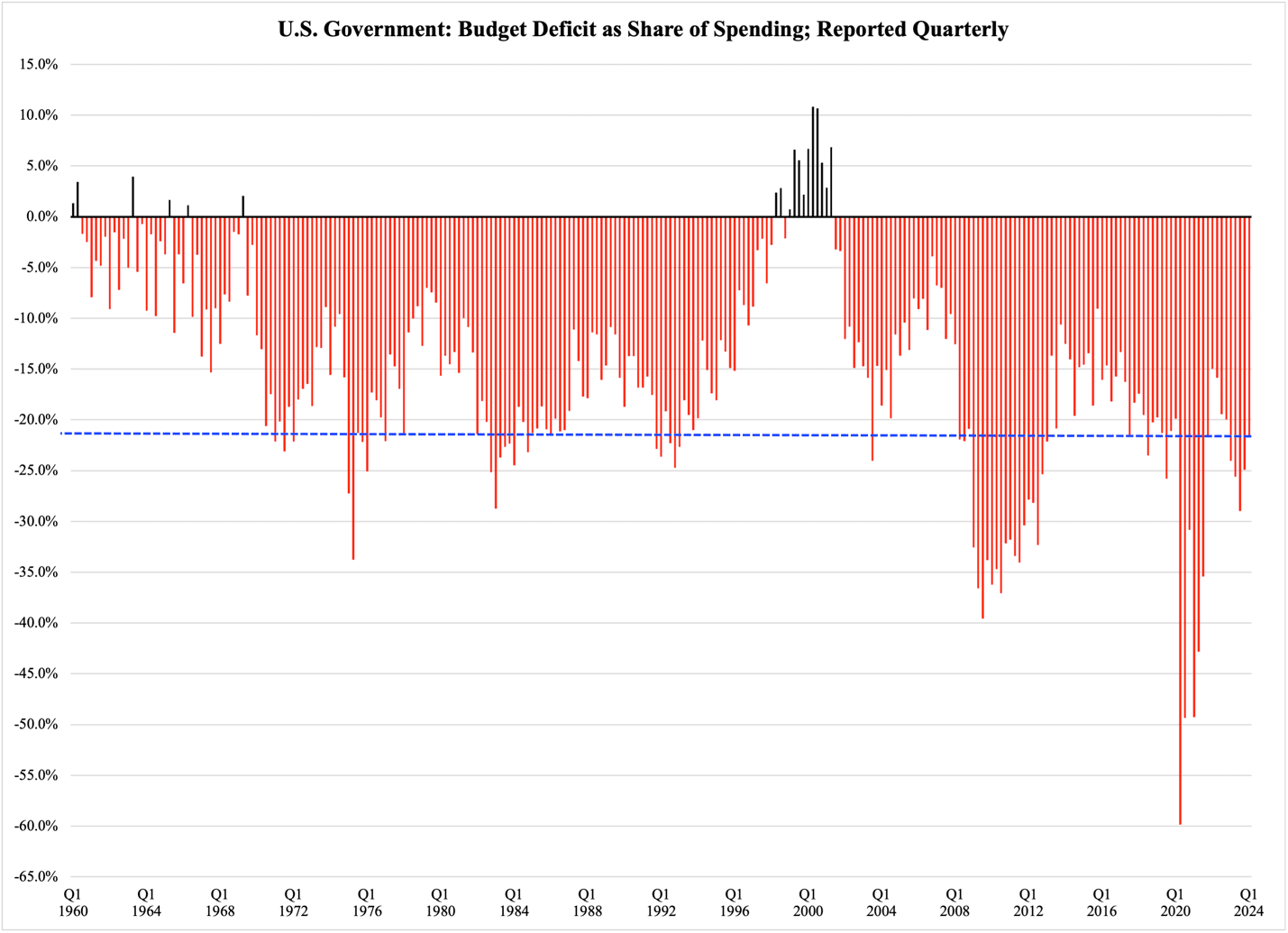

The good news—and it might be the only good news I can report today—is that this deficit share of spending is lower than it was in the preceding four quarters when borrowed money funded 25-29% of spending. The bad news is that as Figure 1 below reports, Congress has made it a decades-long habit to borrow about two dimes of every dollar they spend. The dashed blue line represents the 21.5% deficit-to-spending ratio from Q1 this year:

Figure 1

We can draw a lot of conclusions from these numbers. Among the more painful ones is that Congress is not even trying to pretend anymore that it wants to balance its finances. If they were, they would get their act together and repair their hopelessly broken appropriations process. As things are now, and have been for the most part since Obama was president, federal government spending is determined through recurring continuing resolutions. Originally, these resolutions, which essentially allow spending to continue on an as-is basis for a few days, weeks, or months, were meant to be an emergency measure used only under exceptional circumstances.

Continuing resolutions are by definition useless for structural spending reductions. Since they are part of the broken appropriations process in Congress, the continuing reliance on resolutions means that Congress will not even begin to consider measures to rein in its own spending.

Fixing the budgeting process in Congress is a small first step toward ending the budget deficit. It is far from sufficient, though; another step is to recognize that there is more than one way to account for the deficit. The first way is the one we discussed above, based on national accounts Table 8.3 in the BEA database; that budget deficit is the ‘current’ deficit, essentially a cash-flow definition of the budgetary shortfall.

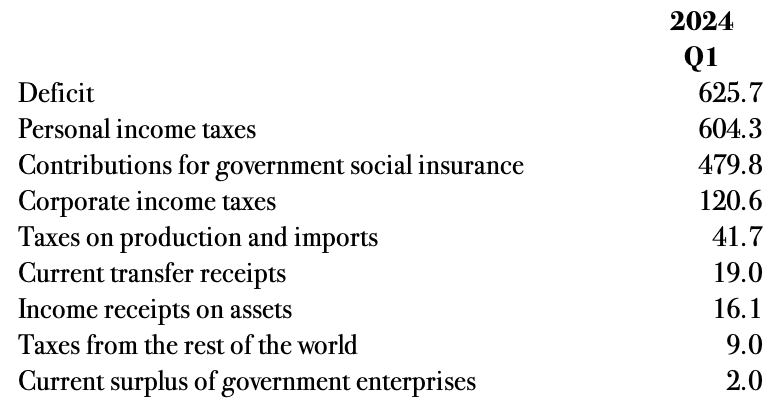

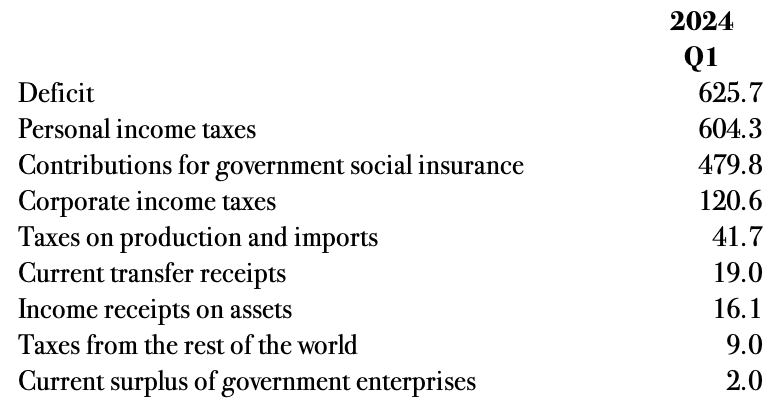

The other definition of the deficit is based on the U.S. Treasury’s debt-to-the-penny measurement of how much the federal government owes. Those numbers show that in the first quarter of this year, the federal debt increased from $34 trillion to $34.6 trillion. This deficit was so big that if we count it as a revenue source of its own, it outsized every other source of money that they had.

Table 1 has the story (numbers in billions of dollars):

Table 1

There are analysts and commentators who would object to using the debt-based definition of the deficit. I am not going to take up time here to discuss their arguments and my counterpoints; all we need to do is acknowledge that every penny of the U.S. government’s debt is a penny that one way or the other must be repaid at some point. Therefore, every time another penny is added to the debt, it is there because the U.S. government did not have enough revenue to pay for whatever it wanted to spend money on.

Put simply: if we want to stop the growth of the debt, we need to actually address the growth of the debt, not just the budget deficit that appears in the federal government’s periodical cash flow.

Stopping the debt growth is an increasingly daunting task. On May 28th, the federal government owed $34,606.2 billion. On the same day in 2023, the same debt was $31,464 billion. This means that in one year the United States government has borrowed another $3,142.2 billion.

Some analysts may try to throw some cold water on the debt worries by pointing to how the federal debt is actually a tad smaller now than it was at the end of the first quarter. On April 1st, the federal debt was $34,627 billion, making the May 28th figure of $34,606 a little bit smaller.

As good as it is to see a period of time where there is no rise in the government debt, there is nothing magic about it. This temporary halt in the growth of the debt is simply the result of tax season: many wealthy people make only one tax payment per year, just in time for the April 15th tax filing deadline. Throughout the year, they save up their future tax payments in a special bank account with high interest; when tax season comes around, they wire one year’s worth of taxes to the IRS. The interest they accrued is their personal reward for being tax compliant.

Once the filing season is over—which is about now—we will see the federal debt climb faster again.