Jules Massenet’s late-life opera Don Quichotte, a scenic pastiche drawn from Miguel de Cervantes’s famous novel Don Quixote refracted through Jacques Le Lorrain’s contemporary play Le chevalier à la longue figure, invites dreamy fantasies of a lost and better world. Massenet called the opera a comédie héroïque, likely a unique designation in the opera world and a contradictory one at that.

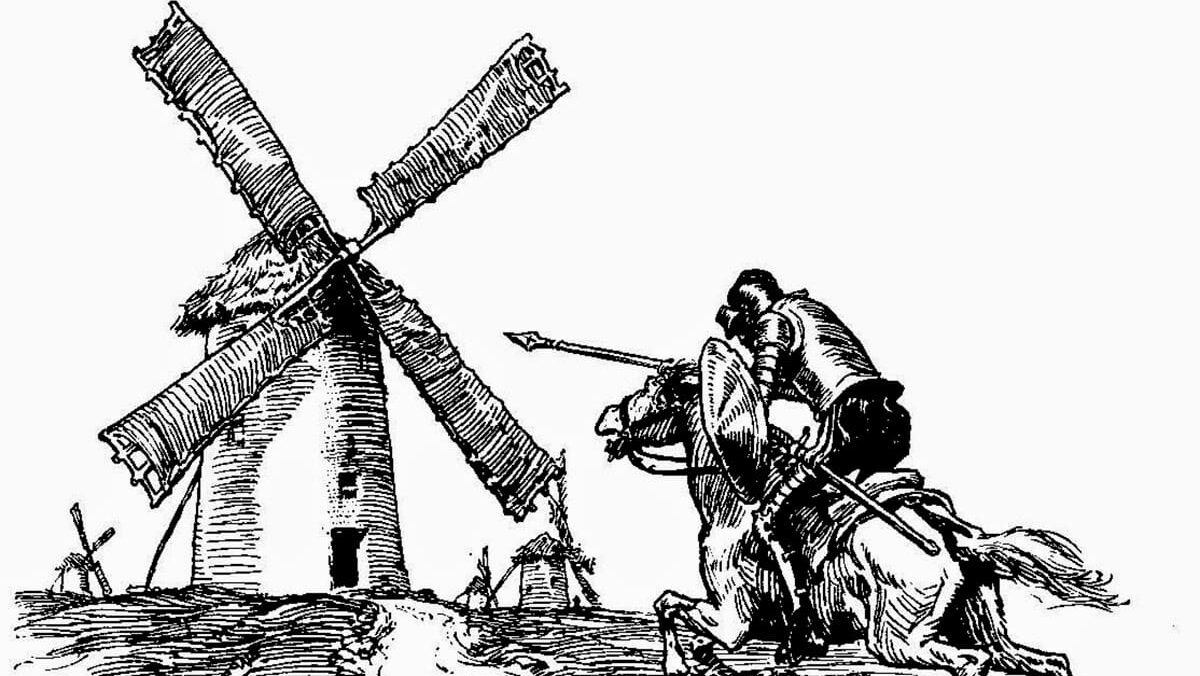

If our own world is disappointing, one could find comfort in the ready conclusion that it was already dead when Massenet took on the subject for his opera, which premiered in cosmopolitan Monte Carlo in 1910. Don Quixote’s famous attack on the windmills made it into the score, which retells the title character’s faithful love for Dulcinea, known here fantastically as “La Belle Dulcinée.” Contemplating her beauty and imagining her to be a lady of great virtue, Don Quichotte risks life and limb to confront bandits who have stolen her necklace. When they easily capture the foolish old man, his unaffected simplicity and naïve attachment to chivalry remove any violent impulse and instead move them not only to free him but also to return the necklace. La Belle Dulcinée is astonished at his feat but turns down his farcical marriage proposal, first laughing at it but then softening to tell him that she is sorry for his hurt, even if she is not and could never be what he imagines her to be. Don Quichotte soon dies, enjoining his sidekick Sancho Panza to dwell on ideals in his mind as he contemplates a star and imagines Dulcinée’s voice calling him to her.

A leading French paper’s review of the opera’s premiere 114 years ago called it “a very Parisian evening,” a comment meant as a compliment. Don Quichotte was Massenet’s last major success. He died eighteen months after the premiere—long enough to write four more operas, none of which are remembered. And, like his title character, Massenet had an unrequited love for the soprano who created the role of La Belle Dulcinée, Lucy Arbell, while suffering bouts of painful rheumatism during the completion of the score.

Telling this story for the Paris Opera’s new production fell to the talented Italian director Damiano Michieletto, who is known for modern stagings that nevertheless impart undeniable truths and trenchant readings of text and score. His Don Quichotte is a 1950s schoolmaster haunted by a mod Belle Dulcinée, whose admirers, clad in high school letterman outfits, penetrate his plain quarters through the furniture. Paolo Fantin’s clever set designs allow for sofas and bookcases with trap doors to admit them. The effect removes Belle Dulcinée’s first-act demonstration from public spectacle to private torment. Don Quichotte’s consolation for his unrequited love and for others lusting after her is a pill washed down by alcohol, the physical reaction to which is coordinated with a sweeping motif in the music. His ‘quest’ for the stolen necklace leads him to a band of brutes who look like the bad boys in Rebel Without a Cause. He makes an approach to Belle Dulcinée and suffers her heartbreaking rejection at a sophomoric dance party. Back in his utilitarian 1950s home, he expires while giving a pained voice to all the same hopes, ideals, and disappointments that Cervantes’s Don Quixote might have had, amplified by the miseries and intrusions of the modern world.

Massenet wrote the title role of Don Quichotte for the acclaimed and inimitable Russian bass Fyodor Chaliapin, who performed it at the premiere, recorded its arias in the following decades, and played the character in a film. It figures on the list of all aspiring basses, if not always very high, and stagings of the opera are generally a vehicle for such singers. In the American bass Christian Van Horn, who has worked through much of the basso cantante repertoire in Paris and elsewhere, Chaliapin finds a fine heir. With his commanding presence and superb legato, Van Horn demands our sympathy and delivers the part with a refined nobility that nearly bows to the character’s shabbiness. Gaëlle Arquez, a sultry mezzo-soprano, developed La Belle Dulcinée’s nuances and caprices to near-erotic perfection, a perfect tormentress at every turn. The splendid French-Canadian baritone Étienne Dupuis sang affectingly as Sancho Panza. Patrick Fournillier’s conducting came at a brisk pace but never failed to neglect the poignant moments.