With Britain and France voting for left-wing governments last week, we can expect European fiscal policy in general to take a turn for the worse. This means more budget deficits, which in turn means more government treasury securities being sold onto the global debt market.

With more debt being sold by more indebted countries, it is only a matter of time before we end up in a new fiscal crisis.

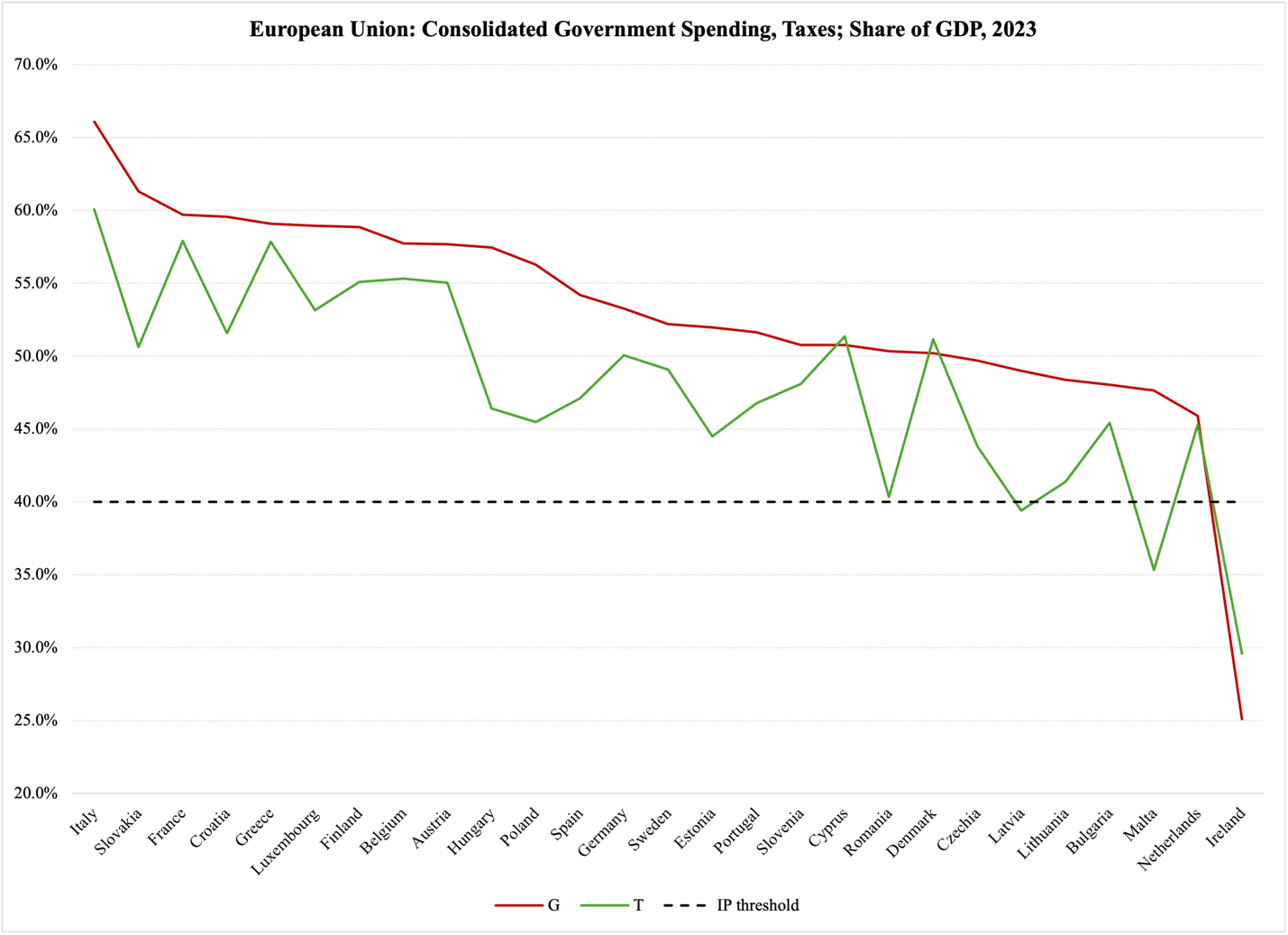

As Britain shows, fiscal recklessness is not limited to the European Union. With that said, Figure 1 below explains how widespread budget deficits are within the EU. The figure reports consolidated government spending and revenue for all the EU member states in 2023. The levels are reported as shares of GDP. The red line, which represents spending, runs higher than the green revenue line in almost every country, which means government is spending more than it takes in from taxpayers.

Only three EU member states were able to balance spending and revenue last year:

Figure 1

This is, of course, only a snapshot of the fiscal situation in Europe; as I explained recently, most EU countries have a tragic record of excessive debts and deficits that goes back as far as 2002. This means persistently high debt levels; where those levels are combined with slow economic growth, the debt-to-GDP ratio rises over time. When it gets high enough, it puts the country’s credit rating in jeopardy.

As budget deficits persist and debt grows, the creditworthiness of the debt-issuing governments will eventually come into question. Since we mentioned France before: they deserved their recent downgrade, and they can look forward to more of the same once the new left-of-center coalition goes to work.

It is not a good idea to push more debt onto the global market when your credit rating is shaky. It means that the supply of your debt exceeds demand, and that the average quality of your debt is in decline. This causes interest rates to rise—raising the cost of existing debt thanks to the rollover effect. At some point along the line of rising interest rates and falling credit ratings, indebted governments are put under rising pressure from debt-market investors to end their fiscal hemorrhage.

This commonly leads to an always-destructive policy response known as ‘austerity.’ Having learned how it works in Part I of this article, we now turn to the consequences of austerity.

The Consequences of Austerity

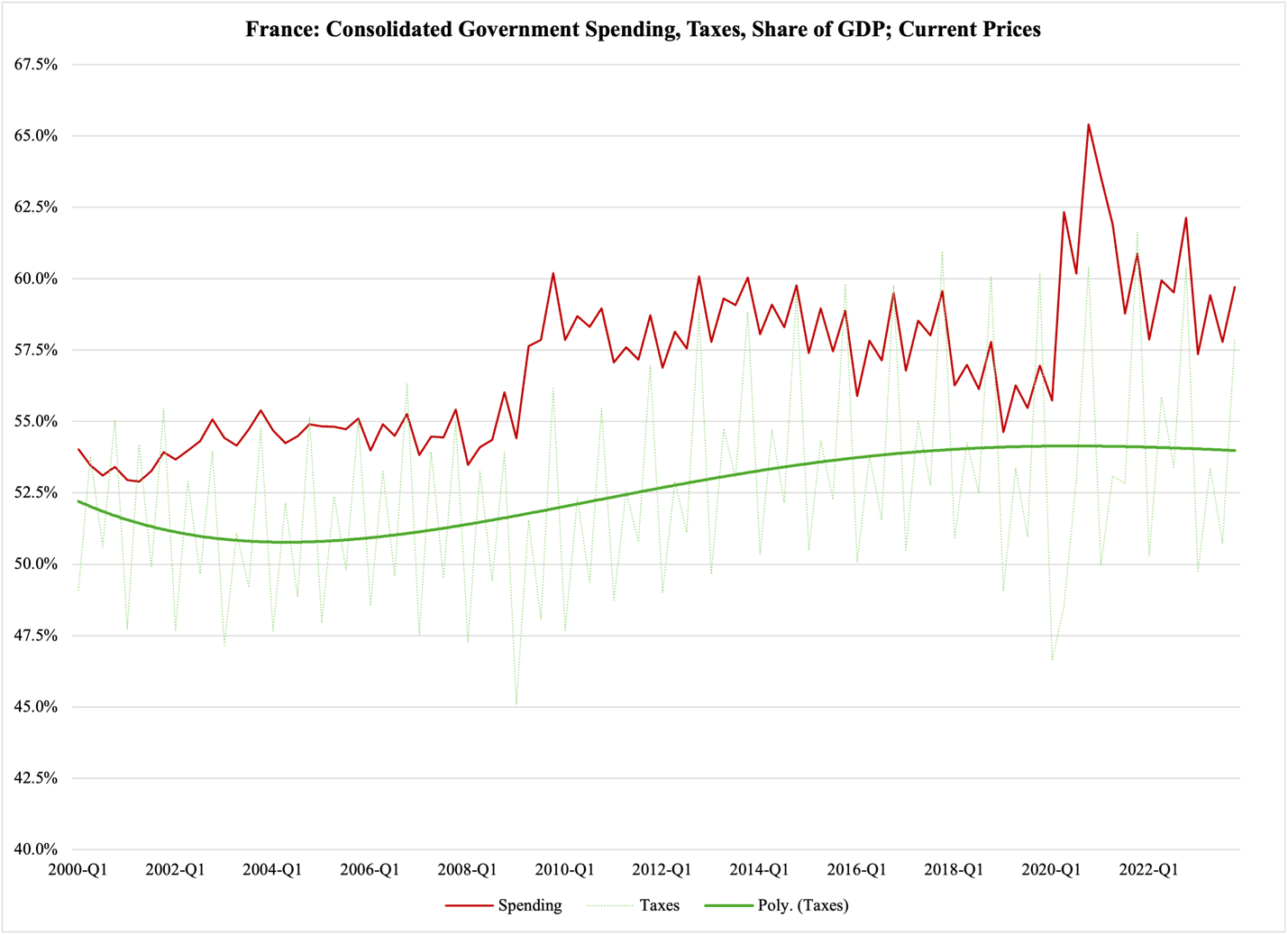

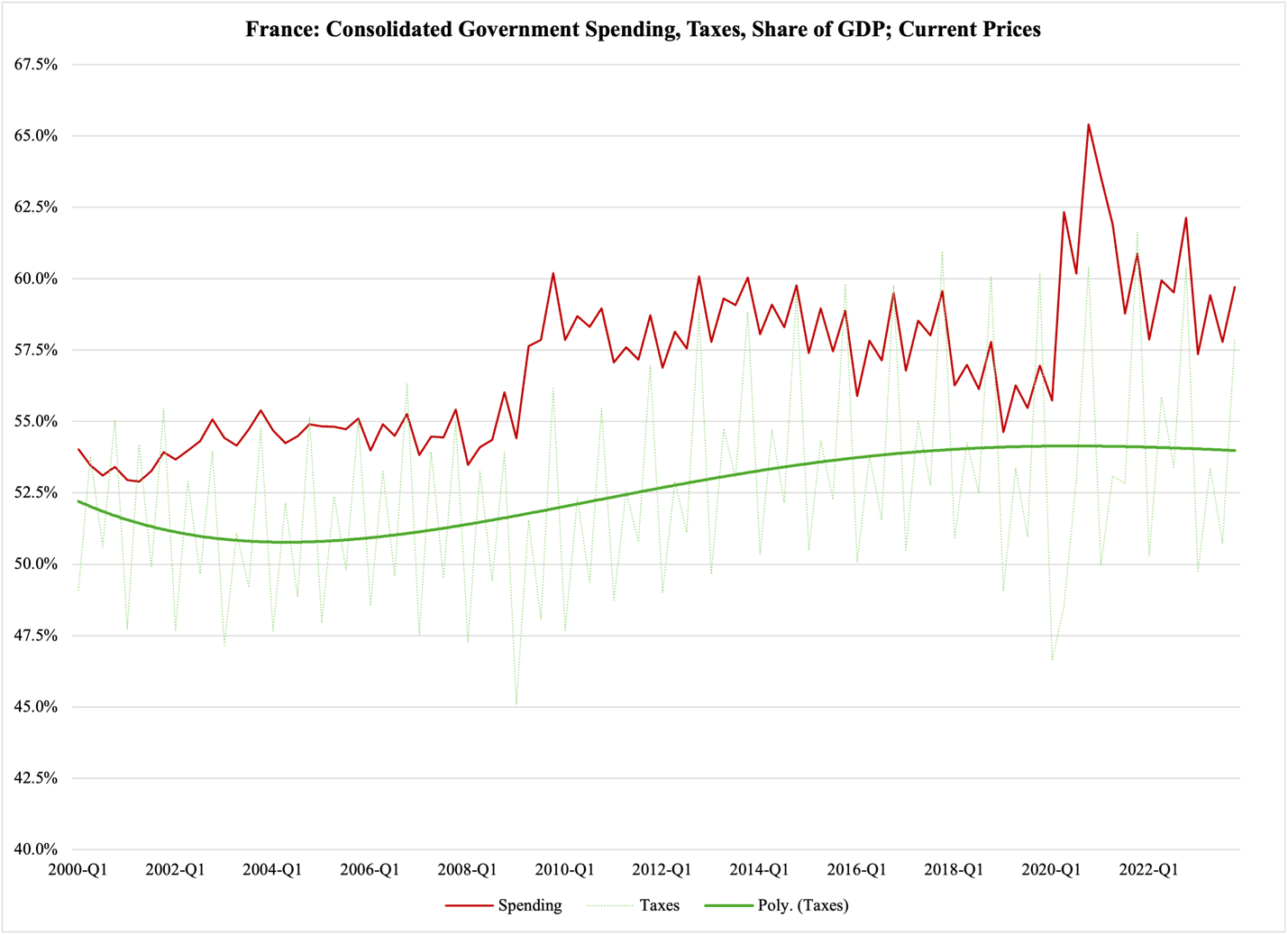

As explained in Part I, France went through an episode of fiscal austerity during the Great Recession of 2009-2012. As I also explained, some critics claim that this cannot have happened, for the simple reason that government spending as a share of GDP did not decline, and even increased.

This critique is based on the fundamental misunderstanding of what austerity policy is all about. While the critics are correct in that austerity aims to reduce the budget deficit, they are incorrect in suggesting that austerity measures should be evaluated based on their effect on government spending as a share of GDP (or the less-often-suggested tax-to-GDP ratio). The purpose of fiscal austerity is not to reduce the size of government—it is to reduce the budget deficit. This is why legislators in countries that have tried austerity have resorted to raising taxes, or cutting spending, or a combination of the two.

Austerity policies should be evaluated based on their purpose and their consequences. The purpose—closing the budget gap—is often achieved on a very short-term basis: when a government reduces spending, the immediate ‘bookkeeping’ picture of its fiscal status improves. However, the consequences of austerity go further than that—and now we are getting to the reason why austerity always fails.

A reduction in government spending without a corresponding cut in taxes—just like an increase in taxes without a corresponding increase in spending—is a net drain of money out of the economy. The policy measure reduces total economic activity.

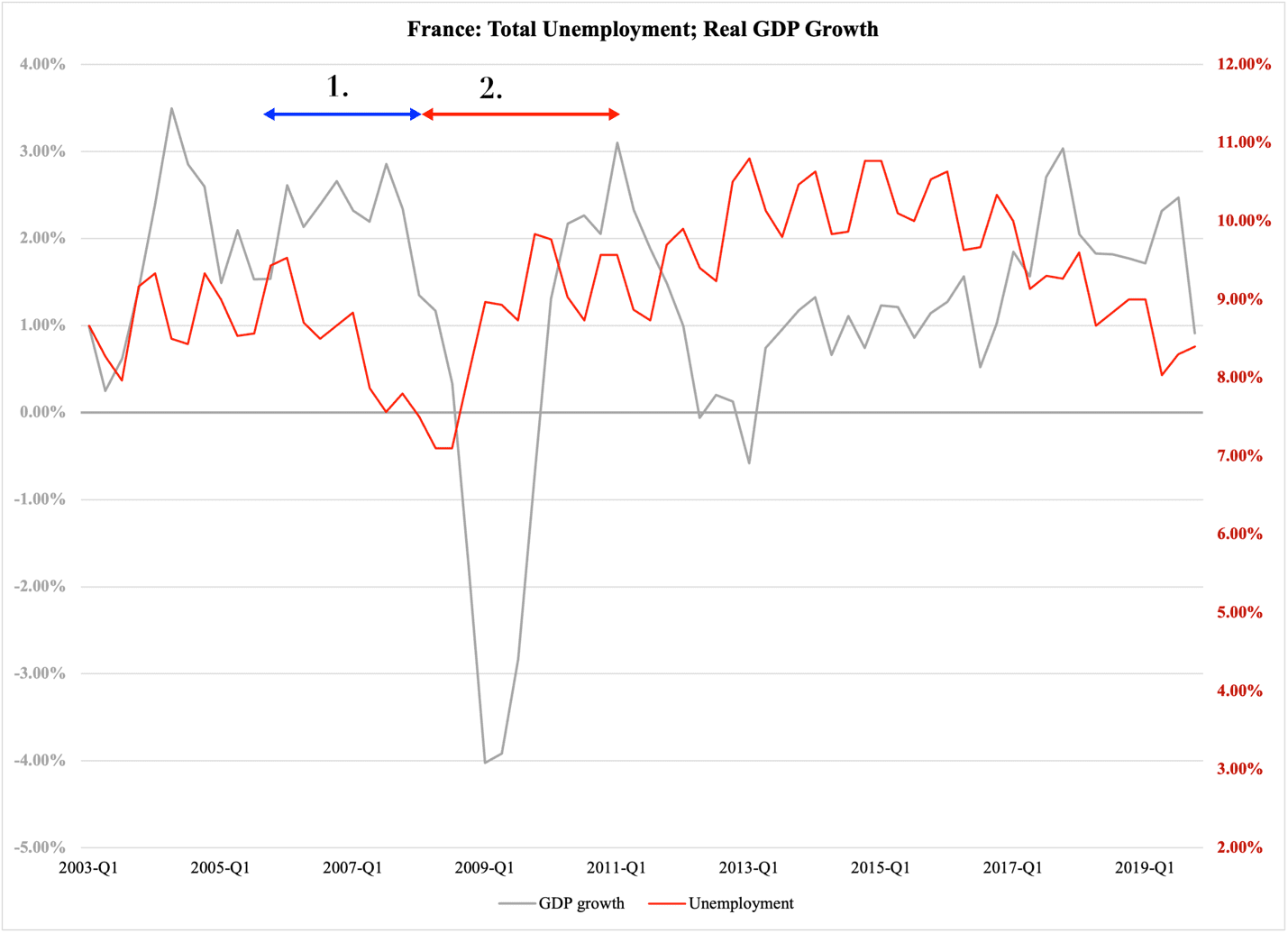

Thanks to macroeconomic multipliers (see Part I for an explanation), a fiscal austerity measure that reduces GDP, and by consequence employment, is magnified and has a larger total effect on the economy than the initial measure had. A cut in spending by, e.g., $100 multiplies to a total reduction of GDP by more than $100; the exact magnitude of the multiplier depends on a number of factors, including tax rates and consumer spending preferences.

A multiplier goes to work within 2-6 quarters after the fiscal austerity measure has been implemented. This means, plainly, that approximately a year after government decided to reduce its spending, GDP falls by more than the initial spending cut. All other things equal, i.e., assuming that there are no other factors at work that will increase GDP, this means that the ratio of government spending to GDP actually rises.

Let that sink in for a moment. Austerity makes government look bigger because it has a depressing effect on the economy. Critics of austerity complain that such policy measures do not reduce government; since austerity policies are never aimed at reducing the size of government, those critics will always be right. However, the reason they are right is not because austerity policies do not work—they are correct because austerity policies work. Those policies reduce the budget deficit—not the size of government—over the short term, exactly as intended.

Figure 2 illustrates how government spending (red) increased as a share of GDP in France during the aforementioned austerity episode. It also explains that taxes went up (green trend line), but the main point here is the uptick in spending as a share of GDP.

Figure 2

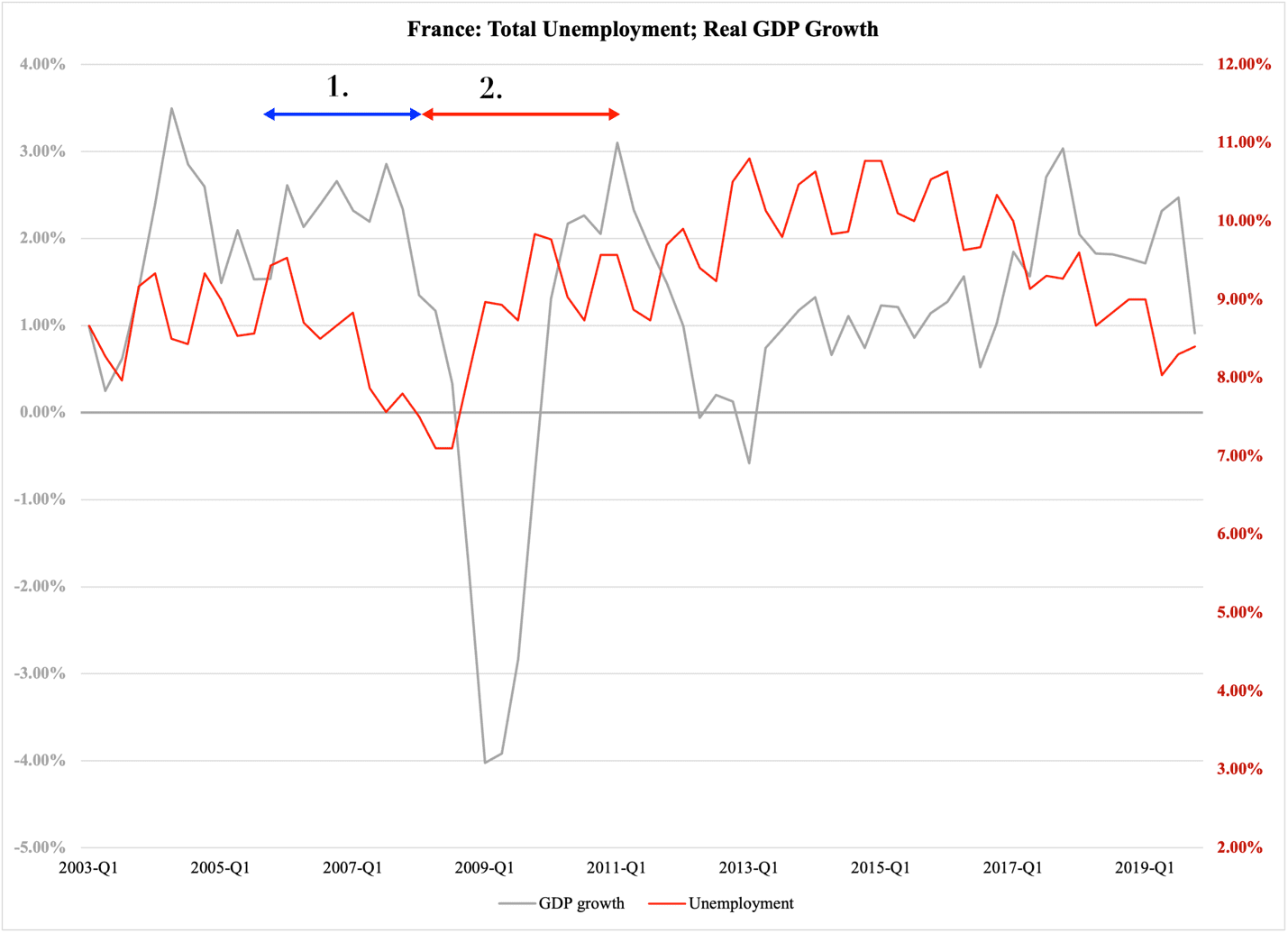

Figure 3 explains how GDP grew at reasonable rates before the Great Recession (arrow 1), fell during the recession, recovered in 2010-2011 (arrow 2), and then stagnated again as austerity measures went into effect in 2011-2012. Correspondingly, unemployment first declined, then increased—putting taxpayers out of work and on to government benefits:

Figure 3

Since both fiscal and consumer multipliers depressed the French GDP, the initial improvements in government finances were quickly eroded by the very consequences of austerity policies. This happened on an even larger scale in Greece during the same period. In other words, austerity always defeats its own purpose.

What, then, is the alternative? If we cannot use austerity to close deficits in government budgets, what should we do?

Alternatives to Austerity

The problem with fiscal austerity is that it does not address the underlying reasons for why government budgets are plagued by deficits. In order to permanently end budget deficits in modern welfare states, you have to structurally reform the spending that constitutes said welfare state.

In Europe, welfare state spending programs account for two-thirds of consolidated government outlays in the euro zone; a tad less in the EU as a whole. The outlays in these programs constitute an economic problem for two reasons:

- They do not fall when the economy goes into a recession and tax revenue declines; on the contrary, the general public demands more welfare state spending in recessions due to rising unemployment and the fact that more people work lower-paying jobs, hence qualify for more benefits.

- They socialize a large sector of the economy. Together with the high taxes needed to fund the welfare state, this socialization removes a sizable share of GDP from the realm of the free market. As a result, there is a decline in the efficiency and productivity of the government-taxed and government-funded sectors. This, in turn, leads to a permanent decline in GDP growth.

The budget deficits that result from this type of spending, and the burden it creates on the economy, are structural in nature. This means that the deficits will not disappear until the very structure of these programs has been altered.

Structural spending reform, which I recently addressed here and here, simply means that no benefits that government provides will be dependent on the person’s income. Instead of paying cash benefits and providing extensive services to the gainfully employed, government programs should provide a limited set of basic benefits. Rather than redistributing income and consumption from ‘rich’ to ‘poor’, government should give every citizen a dignified but basic package of benefits. Only one eligibility criterion would be attached to it: that the person applying for them is in financial hardship by no fault of his own.

A benefits model based on this principle should be coupled with government-provided incentives for private solutions beyond the tax-funded subsistence benefits. That way people will be able to tailor their health insurance, income security, and retirement benefits to their own preferences. This will also limit reliance on the government-provided package.

When the responsibility of government is to provide a set of subsistence benefits, its spending will not grow with rising household income, as it does in most modern welfare states. If anything, government spending will be outpaced by GDP, a principle that Dan Mitchell, president of the Center for Freedom and Prosperity, has dubbed “the golden rule of spending restraint.”

With government spending growing more slowly than the economy as a whole, and with taxes that are proportionate to GDP, the budget deficit under our current welfare state will disappear in short order. If anything, governments that implement this type of structural reform will gradually build budget surpluses, which, in turn, can be used to gradually reduce government debt—not only as a share of GDP, but in absolute terms.

To date, Hungary is the one country that has come closest to reforming its welfare state in line with the model I sketch here. The result has also been a noticeable reduction—in fact close to elimination—of the structural budget deficit. Hopefully, other countries, including hopelessly indebted France and America, will follow the Hungarian example.