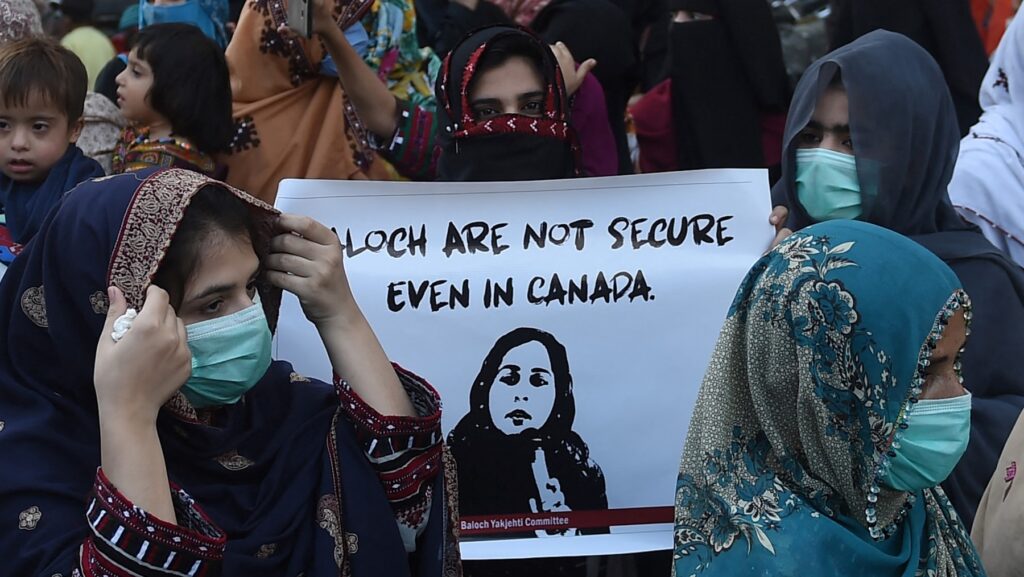

Protesters attend a demonstration after Pakistani human rights activist Karima Mehrab, also known as Karima Baloch, was found dead in Toronto, on December 24, 2020, in Karachi. She had escaped to Canada in 2015 after the Pakistani government accused her of terrorism, according to CBC.

Rizwan Tabassum / AFP

Pakistan is one of the world’s most repressive regimes, as it systematically targets dissidents—critics as well as members of ethnic and religious minorities. Such targeting occurs in various ways, including through abductions, arrests, torture, and murders. As a result, many critics flee the country and seek asylum elsewhere, hoping for a freer and safer life. Yet, even in exile, they are targeted and persecuted by Pakistan’s Intelligence Services (ISI).

Host countries (the UK, Netherlands, France, Sweden, Germany, Canada, and the U.S., among others) have issued warnings, offered protection, and investigated attempted attacks on exiled activists. Activists and diaspora groups consistently allege that the ISI or other state-aligned agencies are behind these actions, citing tactics like threats, harassing relatives, intimidation through local embassies, and the use of paid operatives abroad.

Adil Raja, a Pakistani dissident journalist who now lives in exile in London, is facing a high-stakes defamation trial that began on July 22nd. This is a case he describes as a “strategic lawsuit against public participation” (SLAPP) designed to undermine his journalism and intimidate critics of the Pakistani state. Raja, who is also a former army officer, is accused by a Pakistani brigadier of “defamation” over his statements on social media. The statements in question include allegations of corruption, electoral interference, judicial manipulation, and human rights abuses by the Pakistani military. Raja has criticized the military establishment, particularly the ISI, for weaponizing the UK’s libel laws to silence dissent abroad. On August 21st, Raja’s car was attacked in north London, but reportedly nothing was stolen.

Raja is not the only example. Multiple exiled Pakistani dissidents—including Pashtun, Baloch, and other ethnic activists—have reported digital surveillance, threats, pressuring of relatives back home, passport revocation, property seizure, and forced legal actions via Interpol or local Pakistani embassies in Europe, the U.S., Canada, and the Middle East.

A Canadian-based think tank, the International Forum for Rights and Security (IFFRAS), reported that Pakistani dissidents in Europe, the UK, France, and the U.S. believe that either the ISI or Pakistan’s deep state has targeted them. Incidents include the case of Karima Baloch (Baloch activist) and Sajid Hussain (journalist), who died abroad under suspicious circumstances. The U.S. State Department’s 2023 Human Rights report cites Pakistan among countries accused of transnational repression (i.e., the targeting of critics overseas using threats, intimidation, and potentially violence).

Ahmad Waqass Goraya, a Pashtun blogger-activist living in the Netherlands, has faced abduction, torture, and death threats, as well as a 2021 conspiracy trial where a UK-based individual was convicted for plotting to kill him. The hitman was allegedly hired by Pakistani intelligence and offered roughly £100,000 for the hit.

Taha Siddiqui, another activist from the Pakhtun minority, has lived in Paris since 2018. He alleges multiple visits to his family in Pakistan by individuals identifying as ISI. “They told my father that I should not think I am safe just because I live in France,” he said.

Gul Bukhari, a Pakhtun journalist with dual Pakistani and British citizenship, is a vocal critic of the Pakistani military. She fled to the UK after being abducted in the Pakistani city of Lahore in 2018. The UK police advised her to hide her address and refrain from sharing personal details online. “I feel threatened in London,” she says.

Another Pakistani dissident, Aurang Zeb Khan Zalmay, an exiled editor of the Pashtun Times, has lived in Germany since 2021 while under surveillance by Pakistan’s intelligence officials. He told The Guardian,

Many of my friends are even unwilling to take a selfie with me and post it online out of fear of being watched or interrogated upon their return to Pakistan.

Many of these individuals come from Pakistani regions where ethnic minorities are systematically violated. In Balochistan, for instance, families believe thousands of people have been picked up and tortured by Pakistan’s army and subsequently disappeared.

Some Pakistani critics have been murdered in exile over their advocacy regarding forced disappearances and the extrajudicial killings in their home country. Karima Baloch, for instance, was an activist trying to shed light on enforced disappearances in Balochistan. She was found dead in 2020 at a Toronto waterfront after receiving a threatening message. Canadian police ruled her cause of death was non-criminal, but activists allege it was an assassination and think ISI might be involved in its orchestration due to her activism.

Hammal Haider, her husband, resides in Britain. He says that he does not feel safe in Europe. “Anyone critical of the Pakistani army is a potential target,” he said. “The authorities in Europe must take these threats seriously.”

Sajid Hussain, a Baloch journalist from Pakistan, disappeared in Uppsala in 2020. His body was later found in a river. Swedish police ruled out foul play, but activists suspect ISI targeted him due to his journalism activities. He was allegedly targeted by ISI for exposing military abuses in Balochistan.

Fabien Baussart, president of the Center of Political and Foreign Affairs (CPFA), wrote in his article “Pakistan’s Intimidation Of Its Citizens Abroad”:

Extraterritorial repression is not new for Pakistan, what is new is the ease with which Pakistan authorities are now able to snoop on its diaspora. Technology has made it even easier for them to oppress from a distance. The internet and social-media networks which at first connected and empowered citizens are now being used by the Pakistan Establishment to trap them and go after them. The host countries must take the responsibility of protecting human rights of citizens of other countries to prevent such rogue states from getting away with harassing its citizens abroad.

Lyall Grant, the UK’s former national security adviser, said that any evidence that officers from the ISI were intimidating people in the UK could not be ignored. “If British nationals or residents in the UK who are acting lawfully are being harassed or threatened by the ISI, or anyone else, then the British government would certainly take an interest.”

Since gaining independence as a result of the partition of India in 1947, Pakistan has spent long periods under military rule. Military leaders continue to have a great deal of influence, especially on foreign and security policy, as well as in the economy. This leads to extreme corruption in the government. Pakistan is also facing major domestic policy challenges such as political unrest, a strong presence of terrorist groups, an economic crisis, high levels of government debt, and widespread poverty. The country has been on the brink of default several times—yet, the regime always manages to find the resources to crack down on dissidents even outside of its borders.

Pakistan’s repression of its overseas critics also demonstrates how mass, unvetted Islamic migration affects free speech in the West. Among the Islamic migrants in Western nations are many radicals who work for or are willing to cooperate with foreign governments to target both Europeans and foreigners. These fanatics pose a threat to the security of dissident foreigners and genuine refugees (such as ex-Muslims) who live in the West.