Earlier in the week, I delivered some somber news when I pointed to signs of rising unemployment across Europe. Today, I can balance that up with some good news: inflation is definitely on its way out.

This may not seem to be much to celebrate, given that Europe is heading into a recession, but it is actually worth a smile or two. The alternative, namely, had been that Europe would go into an economic downturn with high inflation—and the combination of inflation and unemployment, a.k.a., stagflation, is far worse than a ‘regular’ recession.

Back in September, I warned that stagflation was still a threat. The only hope for the European economy was to get rid of monetary inflation:

[When] the central bank starts buying government debt and otherwise pumps cash out in the economy, soon enough we begin to see monetary inflation. This type of inflation is both statistically and causally independent of the unemployment levels in the economy.

In other words, monetary inflation—unlike the more normal type of inflation we see in the economy generally—can rise to destructive levels even when the economy is in a recession, people are unemployed, and economic activity is well below the capacity of the economy.

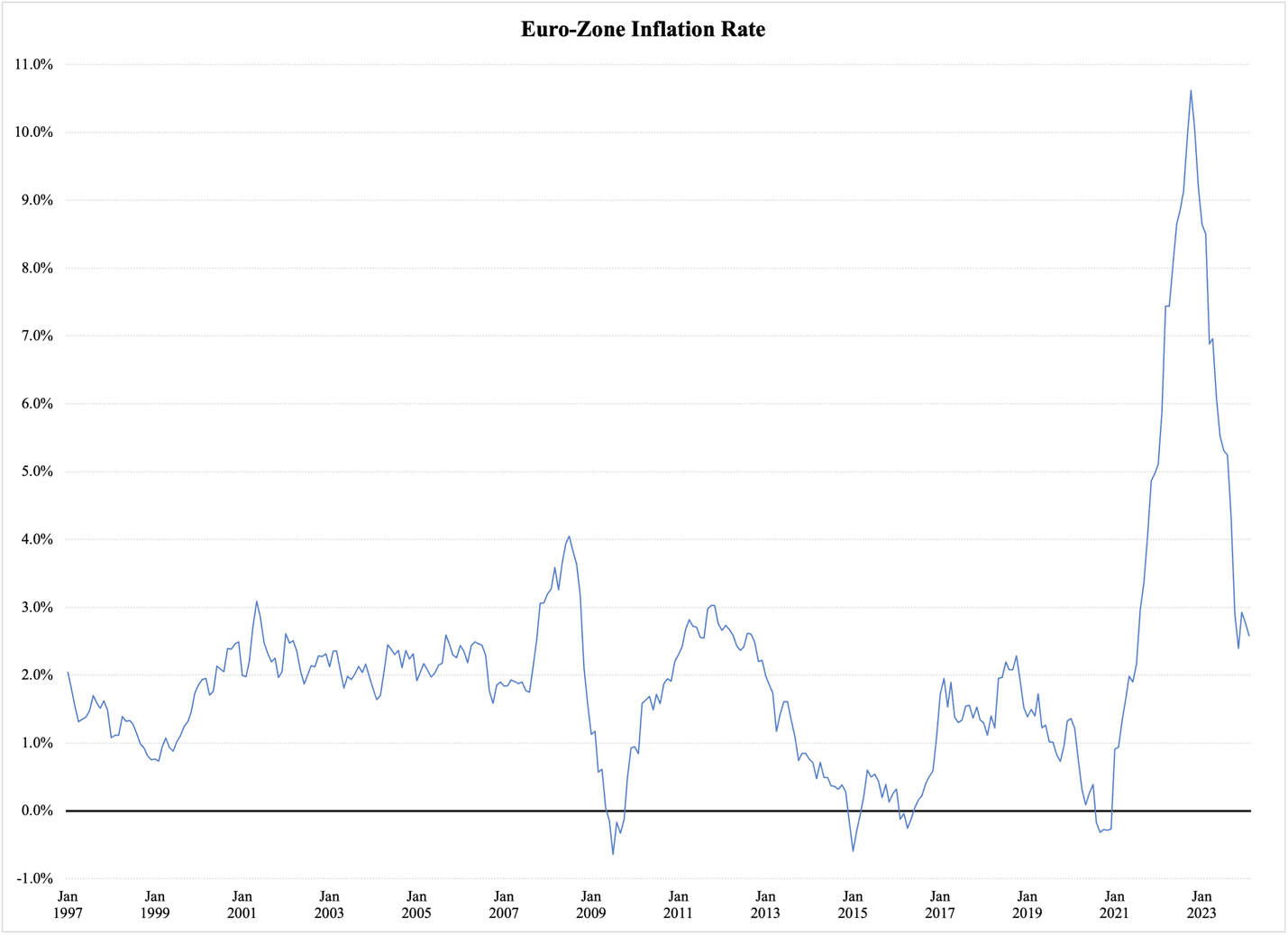

Since there have been signs of a recession in Europe for some time now, the persistence of high inflation through most of 2023 made stagflation a real threat. Fortunately, that has changed: inflation has come down to much healthier levels than we saw last year and in 2022. Figure 1 puts the recent inflation spike in a historical context:

Figure 1

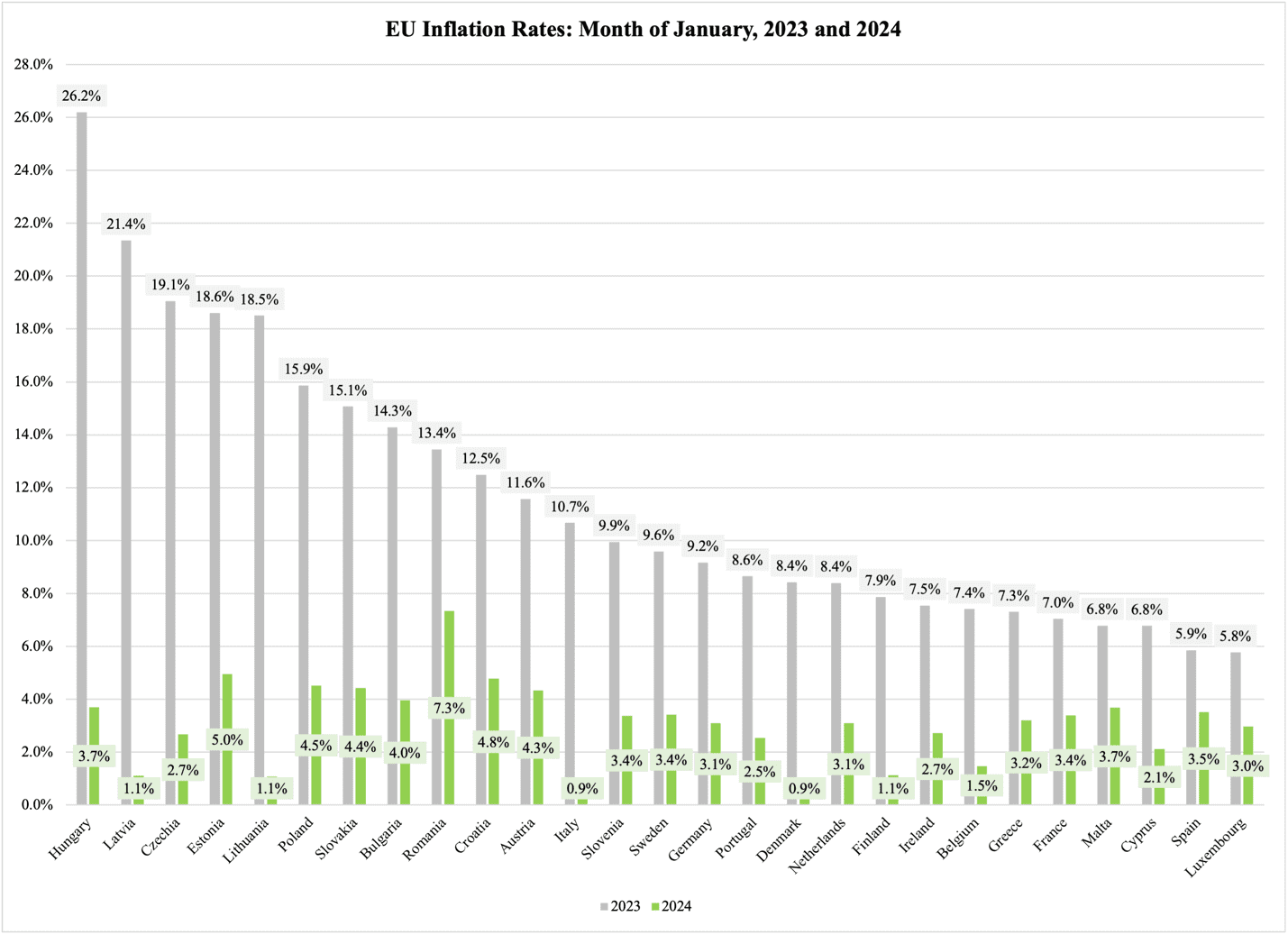

The same trend is visible in all EU member states. Figure 2 compares the January inflation rates for 2023 and 2024, with the countries sorted by their inflation rate a year ago:

Figure 2

The decline in inflation is good news for Europe as a whole, but I would like to give special compliments to Hungary for having pressed down what was a year ago Europe’s highest inflation rate. In one year, they have gone from 26.2% to 3.7%—and they have done it while avoiding a disastrous reduction in economic activity.

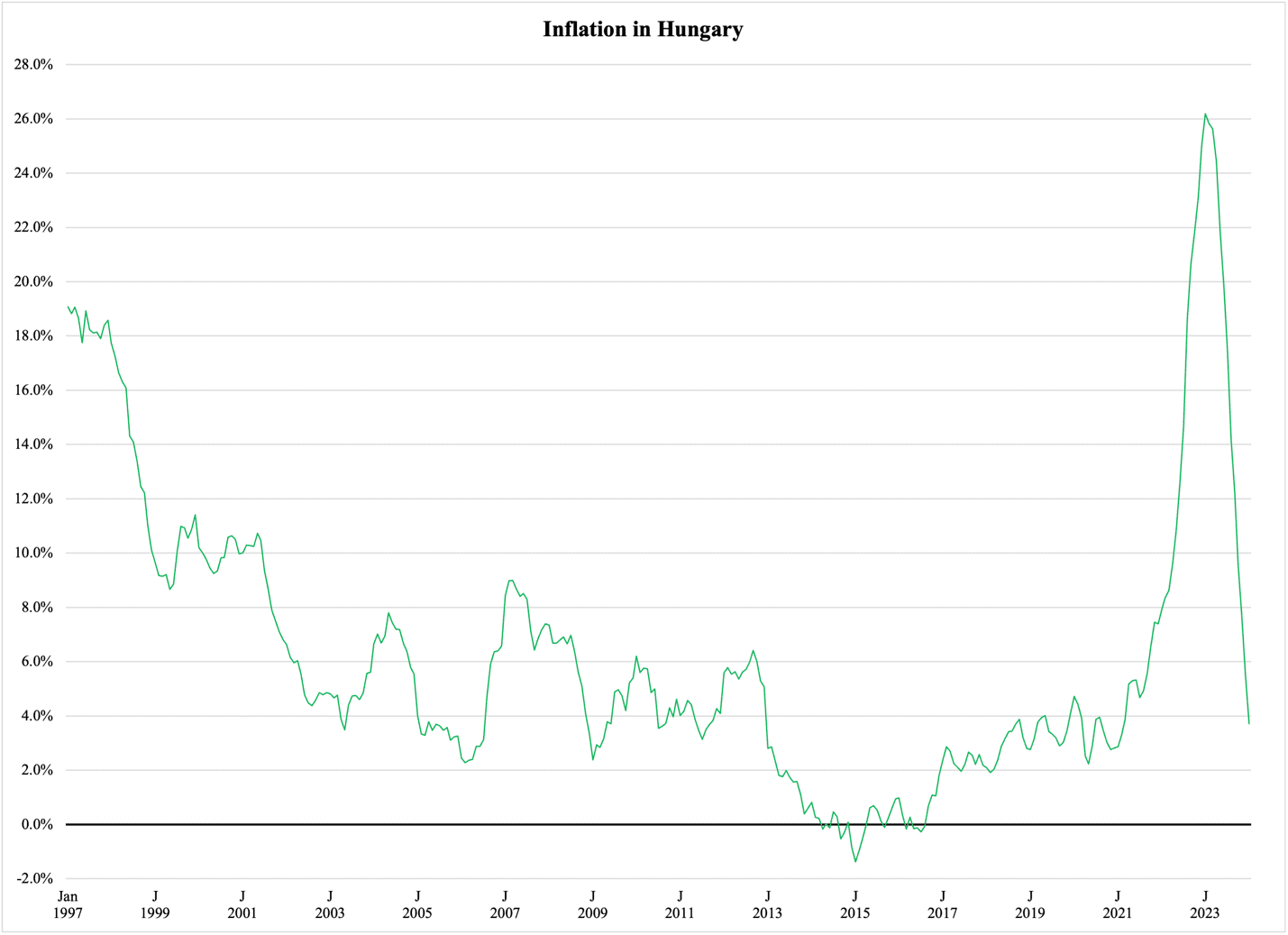

For the better part of the last decade, Hungary led Europe in price stability, and combined low or no inflation with GDP growth rates as high as 4%. Figure 3 reports the inflation history for one of Europe’s best-run economies; their experience shows that a return to price stability, which we had not that long ago, is not only possible, but attainable:

Figure 3

Hungary also excels in terms of low unemployment. Throughout the first nine months of 2023, the jobless rate in Hungary held stable at around 3.9%; in October it began climbing slowly, reaching 4.2% in November and December. The January 2024 rate of 4.5% is a clear sign of an economic slowdown in Hungary, but with 19 other EU member states having a higher unemployment rate, they are still doing well.

The low inflation in Hungary is all the more impressive given that its unemployment rate remains on the low side. According to a classic theorem known as the Phillips Curve, inflation and unemployment vary inversely with one another: when unemployment is low, inflation is high, and vice versa. Although reality has shown that the Phillips Curve has limited applicability, it nevertheless remains a useful staple in economic theory, primarily because it shows how non-monetary inflation varies over the business cycle.

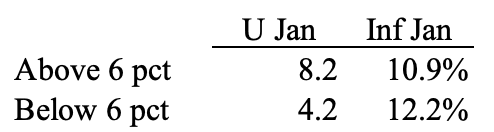

Our recent experience in both Europe and America was with monetary inflation. One of the easiest ways to demonstrate this is to compare inflation to unemployment. Tables 1a and 1b divide the EU’s 27 member states into two groups: those that in January of, respectively, 2023 and 2024 had an unemployment rate (U Jan) above 6% and those with a rate below 6%. In 2023, the 12 countries with higher-than-6% unemployment had an average inflation rate (Inf Jan) of 10.9%; the 15 countries with sub-6% unemployment averaged 12.2% in inflation:

Table 1a

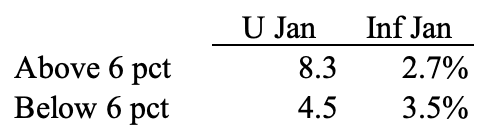

A year later, in January 2024, unemployment has ticked up a little bit, especially in the countries that have less of it. However, the small rise is nowhere near enough to explain the sharp decline in inflation:

Table 1b

Once monetary inflation is out of the picture, we are left with primarily traditional demand-pull inflation, i.e., the kind that comes and goes with the normal up- and downswings in the business cycle.

This does not mean that all inflation left in Europe is of the demand-pull kind. There is likely also some supply-side inflation at work. This is the kind of inflation that results from constraints on the supply side of the economy. These constraints are not related to supply-chain issues left from the pandemic; as I have explained in the past, it was impossible for supply-chain problems to have such pervasive effects as to cause our recent high inflation. Instead, they were caused by the government’s reaction to the pandemic.

However, regardless of what causes supply-side disruptions, the resulting rise in prices is referred to as supply-side inflation. We may still be seeing some lingering regulatory disruptions or disturbances in the European economy, which would explain why inflation has not come down further. Added to the normal demand-pull inflation, a touch of supply-side price pressure would explain the inflation numbers in Europe today.

While a recession is never good news, at least Europe can take comfort in having avoided—albeit narrowly—a bad episode of stagflation. Let us hope that when the recession takes its toll on government finances, there will be no shift in monetary policy by the European Central Bank. If they were to go back to monetizing deficits, the stagflation threat would quickly become very real.