Argentina’s Economy Minister Luis Caputo is seen on TV during an announcement of the new economic measures by the government of President Javier Milei, in Buenos Aires, on December 12, 2023. Caputo announced the devaluation of the peso by over 50 percent to the dollar, as the new government seeks to tackle the country’s deep economic woes.

Photo: Luis ROBAYO / AFP

On December 12th, Argentina’s new president Javier Milei announced a 54% devaluation of the country’s currency, the peso, against the U.S. dollar.

Multiple media outlets referred to the devaluation as “shocking,” but that label appears to have been used mostly because the devaluation was not widely anticipated. However, it lies in the very nature of a currency devaluation that it has to be a tightly kept secret until the moment when it is announced; if news of it is given long in advance, currency speculators will trade the currency—in this case the Argentinian peso—until the devaluation has been completed by the market.

The devaluation is part of the central bank’s policy to fix or manage (semi-fix) its exchange rate. To make such a policy meaningful, the central bank is well served by regulations that limit the flows of financial capital across Argentina’s borders; assuming that such regulations have remained in place, the devaluation of the peso appears to be the launch point for a new, more proactive economic policy in general.

By devaluating the peso, President Milei achieves two major goals, the first of which is to make Argentinian exports cheaper while raising the costs of imports. This will incentivize consumers and businesses to shift their purchases from imported goods and services to domestic producers. Over time, this will stabilize the currency:

A more immediate effect of the devaluation is to make it costlier for Argentinians to shift their savings abroad. It also encourages them to bring their money home:

In other words, there is now a strong incentive for wealthy Argentinians to bring their savings ‘home.’ If they start selling dollars for pesos, they will make a major contribution toward stabilizing the peso.

The willingness of investors to bring their money home depends to a large degree on how credible they believe the new president’s economic policy is. It is too early to say if he deserves their trust or not, but judging from the immediate market reactions to Milei’s devaluation, he seems to be off to a good start.

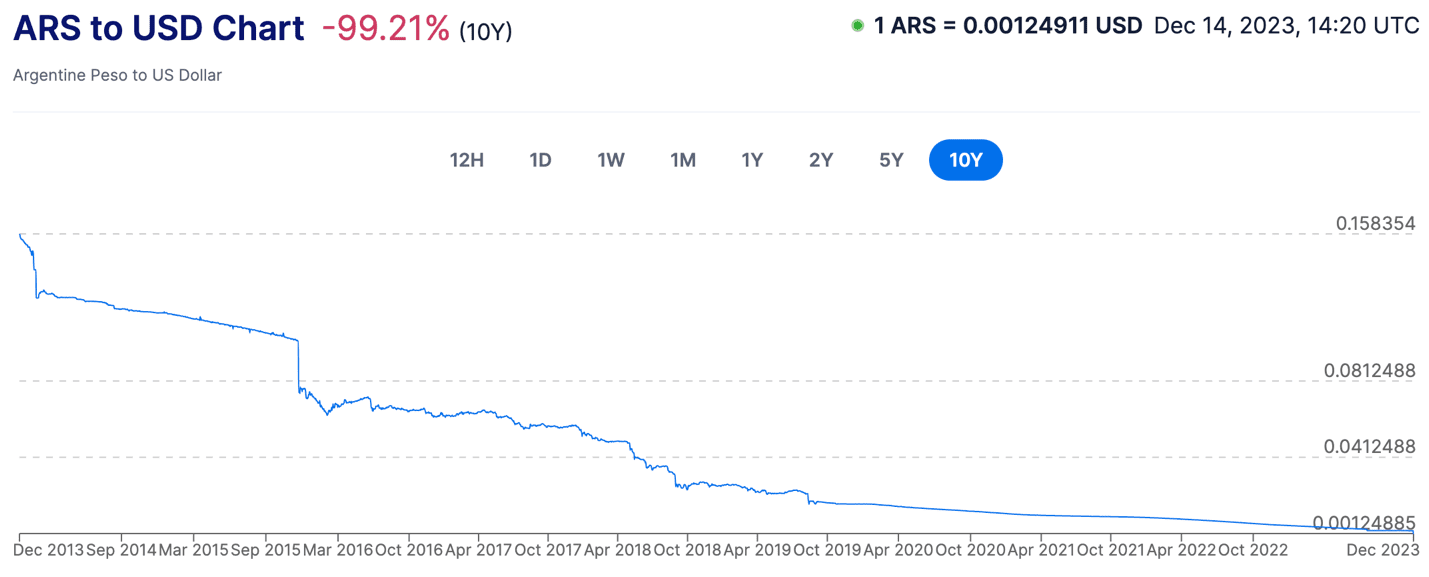

There is another major goal behind the devaluation, and that is to end the plague of inflation in Argentina. It is driven in part by a long-term decline in the value of the peso, a decline that Milei is now trying to end. To see this long-term erosion of the value of the Argentinian currency, let us take a quick look at its exchange rate vs. the dollar. Using xe.com as the source—an excellent source for publicly available exchange-rate data—Figure 1a presents the change in its value that took place when the devaluation went into effect:

Figure 1a

The devaluation looks dramatic when standing alone, but when placed in the context of the past ten years’ worth of exchange-rate data, it actually fades into the background:

Figure 1b

As Figure 1b explains, the peso has lost more than 99% of its value vs. the dollar since December 2013. Before the devaluation, the loss was 98.3%. This means, plainly, that any goods and services that Argentinians buy from abroad, and which are priced in dollars, have risen in price correspondingly.

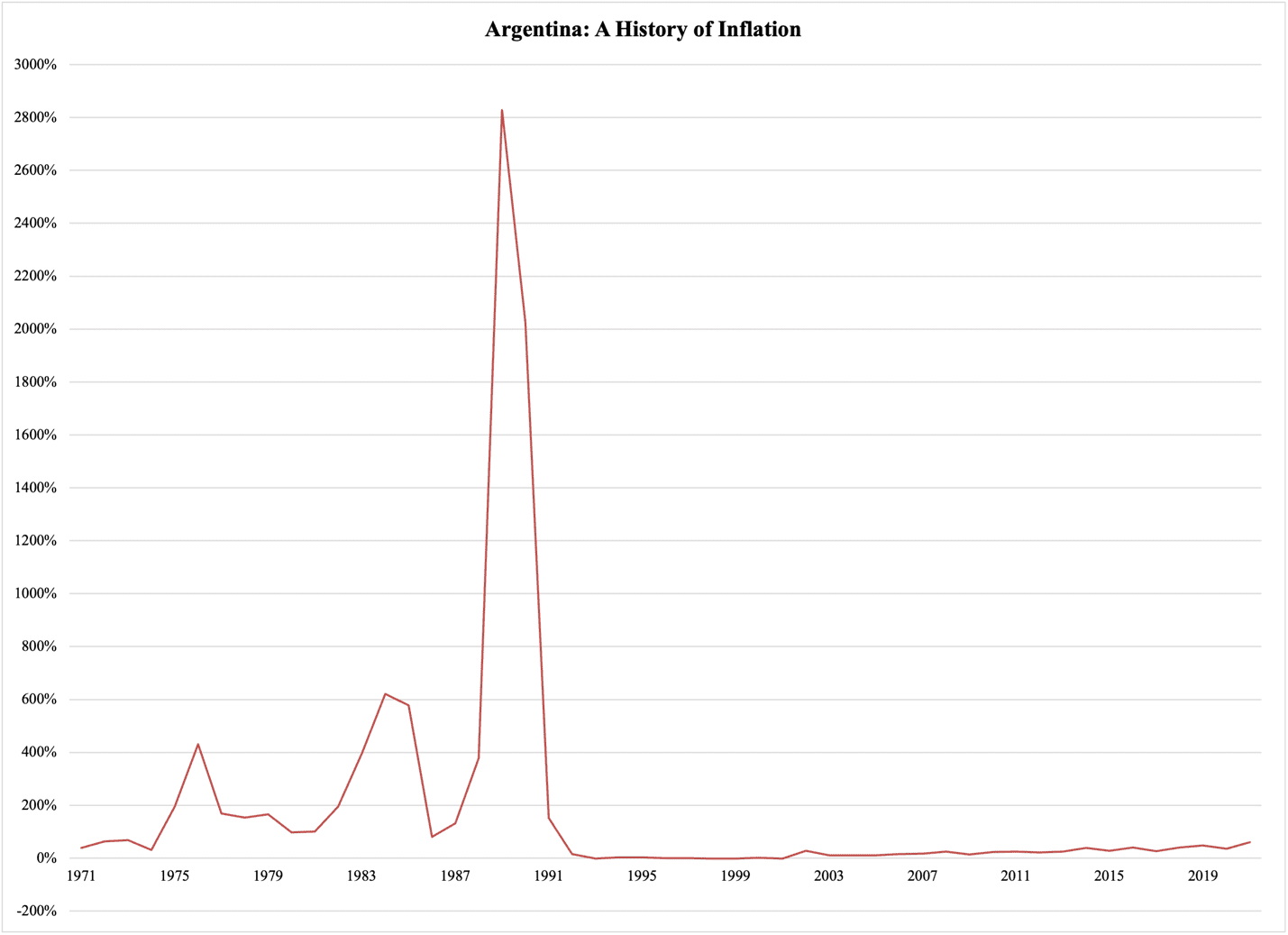

Another big source of inflation is the monetization of budget deficits: it is well established that when central banks print money and buy government debt, they also inject money into the economy in a way that is unsurpassed at causing inflation. The interaction between this inflationary mechanism and the weakening exchange rate has caused an enduring problem with high inflation in the Argentinian economy; Figure 2 reports annual inflation rates (based on the GDP deflator) since 1971:

Figure 2

Given the top at 2,828% in 1989, the subsequent years look like havens of price stability. Unfortunately, as Figure 3 reports that is not the case:

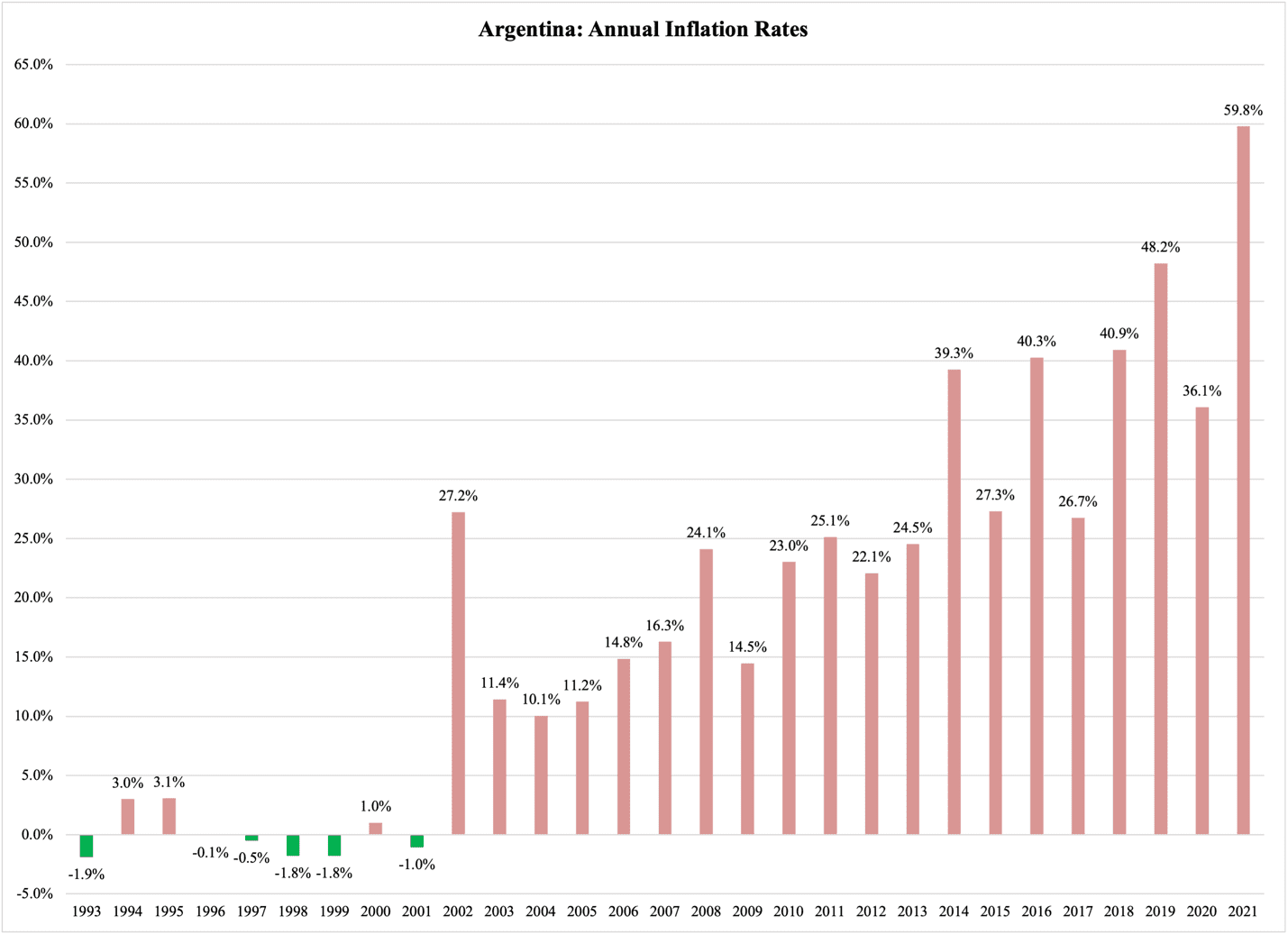

Figure 3

Some sources place the current inflation rate in Argentina at 140%.

The drastic deflation of the peso that has marked the beginning of President Milei’s efforts to rebuild the Argentinian economy can only address the imported part of inflation. In order to fully insulate the country against high inflation, he also needs to bring an end to the monetization of government spending. This, in turn, is done by means of fiscal tightening or austerity, something that Milei has also announced.

If he can stay the course on both these fronts, in about a year, the Argentinian economy will be in much better shape. Its overall macroeconomic structure is sound, with private consumption being the dominant expenditure variable. Exports and business investments account for 16-18% each of GDP, both sound numbers.

Overall, President Milei has launched an intelligent economic strategy. It remains to be seen if it survives the whirlwinds of Argentinian politics.