American inflation has gotten stuck at a level that is considerably higher than what the Federal Reserve would like to see.

Since falling below 4% in June last year, the consumer-price-based inflation index, CPI, has averaged 3.3% on an annual basis. The number for May, which the Bureau of Labor Statistics released on June 12th, shows a year-to-year inflation rate of 3.27%.

As much as this number must frustrate the Federal Reserve, there is one silver lining to it: the stability. At least for the short run, U.S. inflation has parked itself around the 3.3% mark—a full 1.3 percentage points above the Fed’s long-term target. It shows no signs of falling, but also no signs of rising.

Over time, 3.3% inflation is a lot less desirable than 2%. With the cost of living rising by more than 3% per year, workers demand compensatory increases in wages and salaries, which will have to be backed by a 3% improvement in labor productivity. For reasons of marginal efficiency, the jump from 2% productivity gains to 3% is more challenging than the jump from 1% to 2%.

The big question now is why inflation appears to have gotten stuck at the 3% level. Comparing key statistics for the U.S. economy today with where the same variables were 5-10 years ago, there is nothing that prevents inflation from falling to 2%. And yet, it does not. Why?

To answer this question, we need to study the economy at a microeconomic level; as a macroeconomist, I gladly hand that expertise over to others. The main focus of microeconomic studies regarding this question would be to what extent the level of competition has changed in key consumer markets.

During the 2020 pandemic, when governments in both Europe and North America forced private businesses to shut down for an extended period of time, a select few businesses were allowed to stay open. In the United States, e.g., retail giant Walmart was allowed to keep its doors open, while smaller retailers in all the markets that Walmart covers—from groceries to auto repair—were forced to shut their doors.

You do not have to be an economist to draw the right conclusion from this: when the smaller businesses went bankrupt, Walmart and the other few who were allowed an exception by governments improved their market shares. Having lost competitors to selective government enforcement, these businesses had a unique opportunity to increase their prices.

Again, since there have not yet been any studies done on the magnitude and inflationary effect of this herd-thinning drop in market competition, it is impossible to say what share of our recent episode of high inflation is attributable to the government shutdowns. However, I would be more than a little surprised if most of the excess inflation we have now was not attributable to an increased rate of market dominance at the retail level of the economy. On the contrary, I expect that future research will establish that this happened in both goods and service sectors.

Fortunately, we do not have to wait until some microeconomist gets around to finding that my hypothesis is correct; our elected officials are free to pass legislation that reduces regulations, lowers taxes, and in other ways facilitates the emergence of more competition. All it takes is for a large enough number of savvy entrepreneurs to carve out niches in the markets dominated by Walmart et al, and there will be enough competition to suppress monopoly-driven inflation.

With the excess of the current inflation likely being caused by insufficient competition post COVID, it is even more important than for other inflation types that the Federal Reserve refuses to lower its interest rate. Its June 12th decision to maintain the federal funds rate at its current level of 5.33% means that the Fed’s monetary policymakers remain resolute in their crusade against inflation. Here is what their Federal Open Market Committee said about the decision to keep the funds rate unchanged:

Recent indicators suggest that economic activity has continued to expand at a solid pace. Job gains have remained strong, and the unemployment rate has remained low. Inflation has eased over the past year but remains elevated. In recent months, there has been modest further progress toward the Committee’s 2 percent inflation objective.

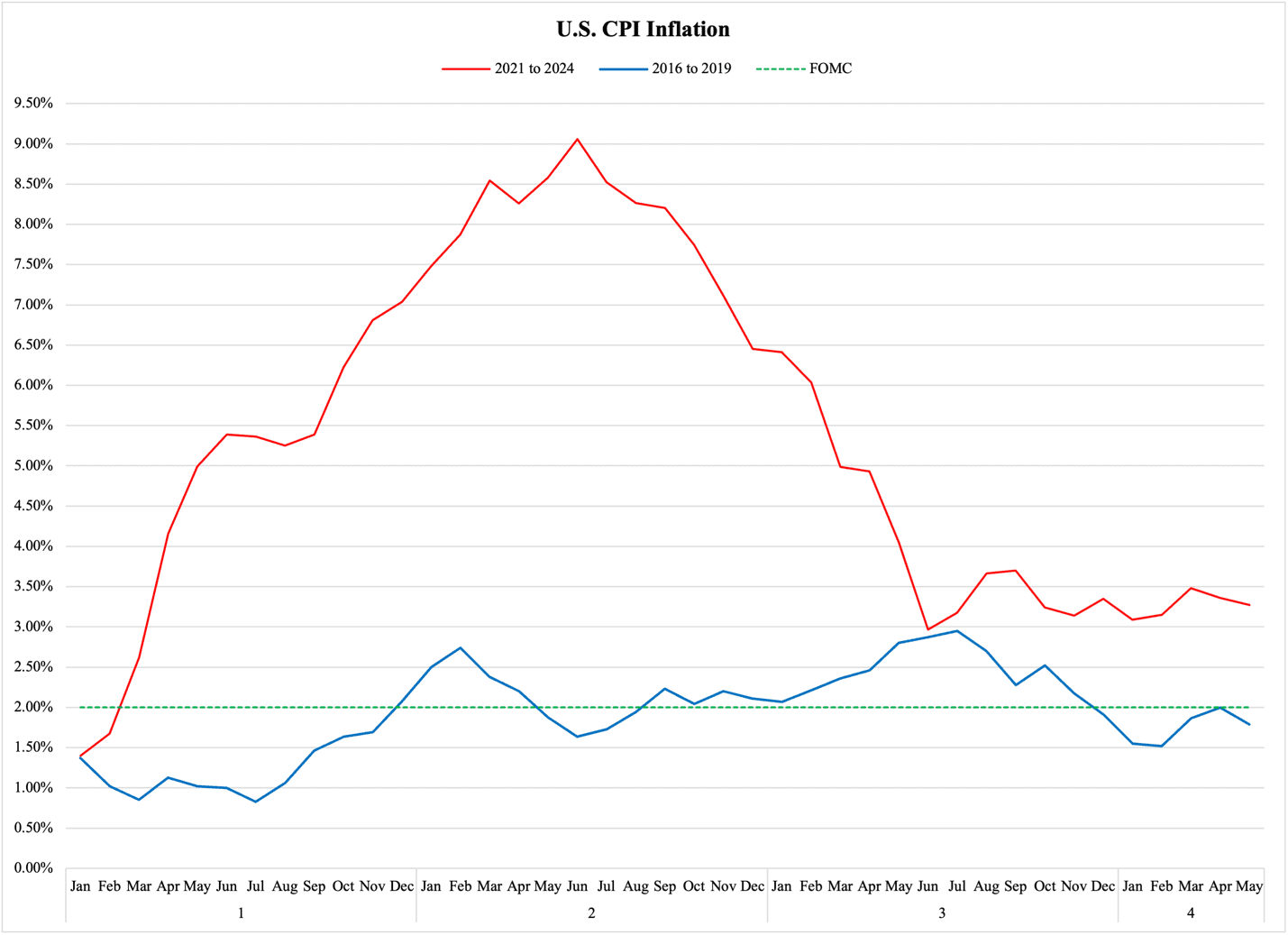

The modesty of that progress is visible in Figure 1, which compares inflation from 2021 to May this year (red) with inflation from 2016 through May 2019 (blue). The Fed’s 2% target is included for reference (green):

Figure 1

Given that one-third of the current inflation—equal to the difference between actual inflation and the central bank’s target rate—is caused by weaker market competition, the Federal Reserve board may have to wait a while before they can cut the funds rate. If the Fed grows impatient, it may decide to raise its funds rate by a quarter point. This would cool off the economy and thereby dampen the inflationary pressure.

I would not recommend this. With weaker competition throughout the economy, market-dominant businesses are less price-sensitive in an economic downturn than they otherwise would be. It would take a relatively drastic rate hike to break the back of this inflation; on the other hand, the higher rates that would sprawl through the economy as a result of such a decision could easily cause a recessionary over-correction.

Hopefully, the Federal Reserve will have the patience and level-headedness to sit this one out. The only change in the current trajectory of the U.S. economy that we can expect will be a recessionary one. When it comes is difficult to predict, but it will come at some point.