Polish Prime Minister Donald Tusk has decided to go after the president of the National Bank of Poland. According to Bloomberg on March 20th, parliament members of the party that Tusk represents

accuse [central bank governor] Glapinski of engaging in irregularities tied to the central bank’s pandemic-era bond-buying program, pushing through an abrupt interest-rate cut ahead of last year’s general election and misleading the government over central bank results

The first and third accusations are legal in nature, with the first one hinging on the extent to which the central bank is statutorily or constitutionally allowed to buy sovereign debt. If such purchases are permitted, the next question is what counts as sovereign debt; since the controversial investments allegedly targeted government funds, not the regular government budget, this accusation may depend entirely on the legal definition of those funds.

The third accusation is likely going to boil down to what accounting or audit principles the Polish central bank is required to use. These rules vary greatly from country to country, but generally speaking, central banks are not prone to transparency. There are good reasons for this, including the need to protect the integrity of the banking system, which central banks are normally assigned to supervise.

Unlike these two accusations, the one about “an abrupt interest-rate cut” is a matter of monetary policy. As such, it is easily dismissed based on monetary policy data, but also based on the sovereign status of the Polish central bank.

As far as sovereignty goes, the Tusk government apparently believes that the central bank violated its own status by timing an interest rate cut last year with the October 12th parliamentary election. Before we get to the actual facts of that rate cut, let me point out that central bank sovereignty is not a novel idea. It was developed by monetary scholars in the 1970s in response to experiences with high inflation. Based largely on monetarist economic theory, the principle of central bank independence says that

a) the board of the central bank should be the only decision-making body responsible for monetary policy; and

b) the central bank shall never intentionally coordinate its monetary policy with the government’s fiscal policy.

For those who wish to learn more about central bank sovereignty, I can recommend “Central Bank Independence—Economic and Political Dimensions” in the National Institute Economic Review (April 2006) by Ottmar Issing. When he wrote this article, Issing was a member of the Executive Board of the European Central Bank.

This is no coincidence: the European Central Bank was constructed to be independent in this fashion. The Federal Reserve enjoys at least the same level of independence.

The National Bank of Poland has a similar status, which means that its decisions on monetary policy by default should be assumed to be independent. Any accusation that it failed to maintain its policy independence, and instead acted dependently, will have to bring formidable evidence to the table.

Bluntly speaking: the Tusk government will have to demonstrate, using economic theory and a wealth of statistics, that the central bank’s interest-rate cut in October 2023 was directly contrary to what it would have done, had it properly lived up to its sovereignty.

It is easy to show that no such evidence exists. On the contrary, all the relevant variables point in the very opposite direction: the National Bank of Poland did exactly what one could expect it would do as a sovereign central bank.

The media has not been very good at covering this controversy. As a representative example, here is what the Financial Times (subscription required) had to say. The Polish central bank

cut interest rates by 0.75 percentage points just one month before the October elections when inflation was still in double digits, a move the Tusk coalition has claimed was politically motivated.

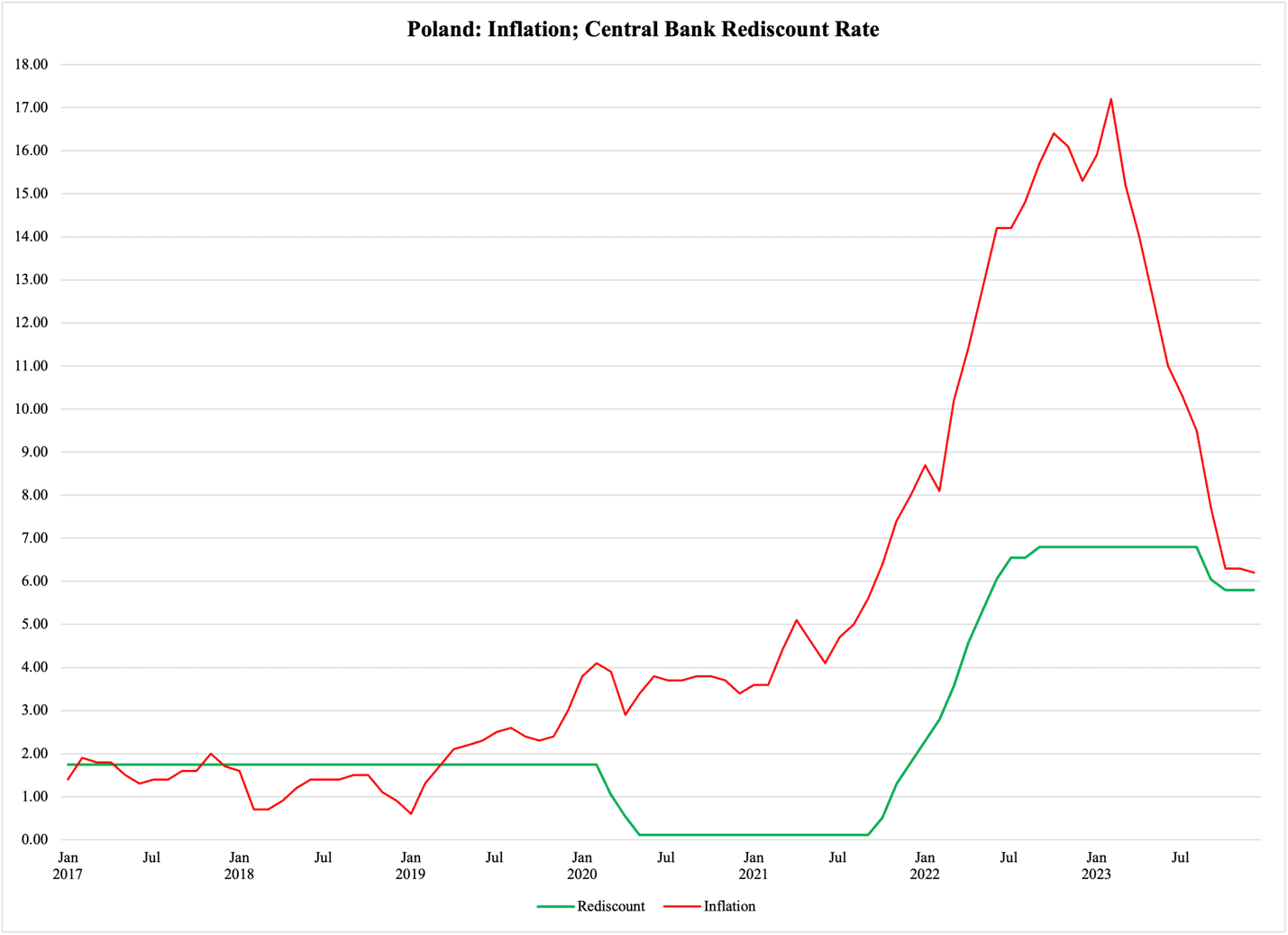

There is one half-truth in this quote, and one outright lie. The half-truth is that the Polish central bank did indeed cut its interest rates in September, i.e., the month preceding the election. However, it also made a cut in October. Looking at the rediscount rate, which effectively is the midpoint rate of the portfolio of interest rates that the central bank operates with, the September cut lowered it from 6.8% to 6.05%. The October cut lowered the rate further to 5.8%.

If inflation had been on the rise at this time, these two cuts would have been very suspicious. However, that was not the case—inflation was on its way down. Had inflation been in the double digits, it would have been reasonable to raise questions about the two cuts.

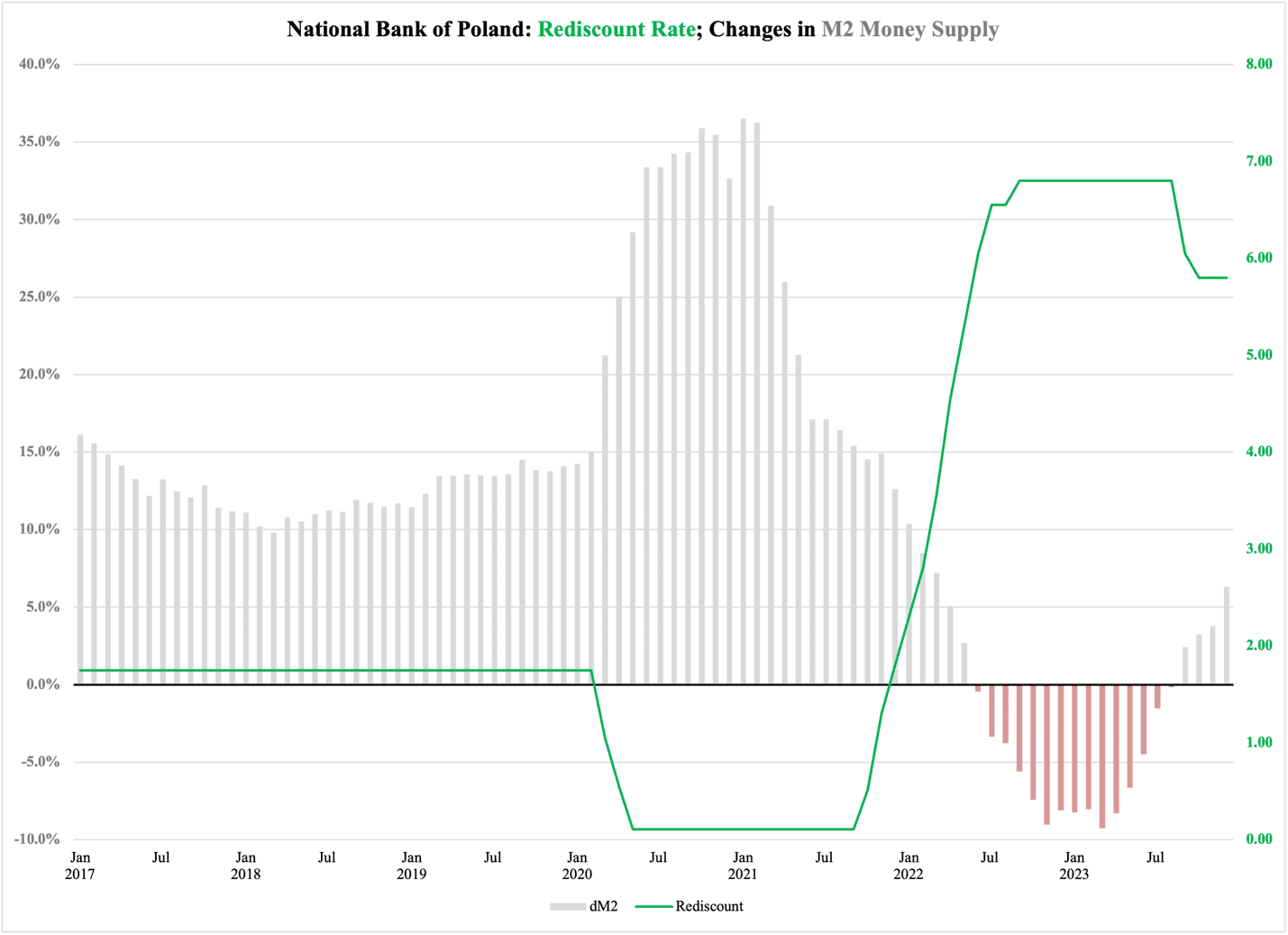

As it turns out, inflation was falling, and it was already well below double digits. To see how the rate cuts align with the inflation trend, let us work through two charts. Starting with Figure 1, it pairs the rediscount rate with the year-to-year monthly changes in money supply (M2) for 2017-2023.

From 2017 through 2019, the rediscount rate held steady at 1.75% (see the right vertical axis); expectably, this rate is paired with a stable growth rate of the money supply. The rate was high, 12.6% per year, but what counts in this context is its relative stability:

Figure 1

During the pandemic in 2020, the National Bank of Poland did what most central banks did at the time: it drastically increased the money supply to counter the adverse effects of the pandemic-motivated artificial economic shutdown. For the better part of a year, the M2 money supply expanded at almost three times the rate at which it had grown in the preceding three years.

The drastic monetary expansion lowered the rediscount rate in three steps, from 1.75% to 1.05%, then to 0.55%, and finally to 0.11%. It remained at that level until, in October 2021, the central bank began a series of rapid-fire rate hikes. In September 2022 the rate reached 6.8%, where it remained for one year.

As Figure 1 shows, during the interest-rate plateau, the Polish central bank reduced its money supply. This is essential as we compare the interest rate to inflation in Figure 2:

Figure 2

When the central bank ended its rate hikes in September of 2022, it had seen enough information to confidently conclude that inflation had reached its peak. When the contraction of the money supply began (Figure 1) it made a tangible difference in inflation; since reaching a top of 16.4% in October 2022, the inflation rate has fallen almost uninterruptedly.

But why did the Polish central bank cut its interest rates in September and October last year?

There is a simple answer to this question. About the same time as inflation started to come down, as Figure 3 reports (from xe.com), the Polish zloty began growing stronger vs. the euro:

Figure 3

The strengthening of the zloty basically ended with the central bank’s two interest rate cuts in September and October last year. There were good reasons for these cuts: Polish exports were beginning to feel the pain of the rising exchange rate, and the Polish economy—like much of Europe—was showing the first signs of a looming recession.

In other words, the fight against inflation was beginning to take a toll on the real sector of the economy. Thanks to the fact that inflation was coming down comfortably, the central bank could take other policy goals into account as well. By executing two prudently sized rate cuts, the National Bank of Poland has not saved Poland from a recession, but it has definitely moderated its consequences.

In short: the Tusk government’s accusations against the central bank of politically motivated monetary-policy manipulation are baseless. They would be wise to drop them altogether: it would be detrimental to the status of the Polish central bank if the Tusk-led government goes ahead with its accusations. They would not only destroy the central bank’s reputability but—ironically—also shatter its status as a sovereign monetary authority.