There are a number of reasons why EU member states that are not yet in the euro, should maintain their national currencies. As I have explained in analyses of Croatia, Hungary, and Sweden—Part I and Part II—the loss of monetary independence has multiple consequences that are rarely if ever discussed ahead of accession into the currency union.

The euro accession spotlight has now turned to Bulgaria, where proponents of the currency union are close to winning the argument. Ironically, the one reason currently keeping them out of the euro zone is also the one reason why they should not join the euro.

In an interview on April 18th with the Bulgarian News Agency, Dimitar Radev, the governor of the Bulgarian National Bank, explained that his country will not be joining the euro zone on January 1st, 2025, but that its accession “is a possible and, at this stage, more likely scenario” later next year.

Governor Radev does not give any substantive reasons for the delay, other than concern for the inflation rate in the Bulgarian economy. He wants to see it drop further than the 3.5% it had fallen to in February and the 3.1% rate in March:

Although inflation according to the Harmonised Index of Consumer Prices has dropped for the eighth consecutive month, the decrease should be more tangible in view of the European Central Bank’s June convergence report on Bulgaria’s entry into the euro zone

There is a great irony in this. The Bulgarian National Bank is unable to make any contributions toward a lower inflation rate. Therefore, so long as inflation is the main obstacle to euro accession, it is unreasonable for Governor Radev to try to predict when the euro can replace the lev.

Here is Radev’s explanation of how Bulgaria can reach a lower inflation rate; let us first listen to him, then translate his econo-speak into plain English:

When there is a currency board arrangement in place, the central bank has more limited options to control inflation, so the role of fiscal policy in influencing prices is even greater, Radev said. “The budget should be counter-cyclical, or, in other words, anti-inflationary, which it is not at the moment.”

The Bulgarian National Bank has kept the lev tightly pegged to the euro since the euro was minted. The target exchange rate has been 1.9558 levs per euro, although, in the early years, there were minor fluctuations that indicated a ‘bandwidth’ peg rather than a hard one. Since 2006, though, the rate appears to have been on a hard peg, which for the Bulgarian government has led to a de facto loss of monetary independence.

By necessity, a fixed exchange rate forces the central bank to focus all its monetary policy on defending the exchange rate. If there is an increase in exports from Bulgaria, an inflow into the country of tourism, or a generally rising interest in investing in the country, then the lev is subject to appreciation pressure. To counter this, the central bank has to print more levs to neutralize the rising demand for the currency.

By the same token, reduced demand for levs means the central bank has to withdraw currency—technically shrink money supply—in order to prevent the lev’s weakening vs. the euro.

There is nothing dramatic in these monetary policy maneuvers. They are perfectly natural to a central bank that has pegged its own currency against another (or an index of other currencies, which was common in Europe before the euro). However, because of the complete focus on the exchange rate, the central bank has to capitulate on all other fronts where monetary policy could be useful. The pursuit of strong GDP growth, full employment, and price stability becomes the responsibility of fiscal policy, namely taxes and government spending, for which the nation’s legislature is responsible.

In his remarks on the role of fiscal policy, Governor Radev suggests that it needs to be “counter-cyclical” in order to keep inflation low. What he means by this is simple:

This all works well in theory. In reality, there is very little that fiscal policy can do to manage inflation. There are three types of inflation, the least known type being structural: when there are regulatory and other institutional hindrances in the way of the market economy, the cost of doing business increases as a result. Dynamically, this translates into a higher rate of inflation than would otherwise be the case.

The second inflation type has to do with the interaction of supply and demand in individual markets. When demand rises faster than supply, the result is an ‘overheating’ of the economy with a higher rate of inflation than the economy normally has.

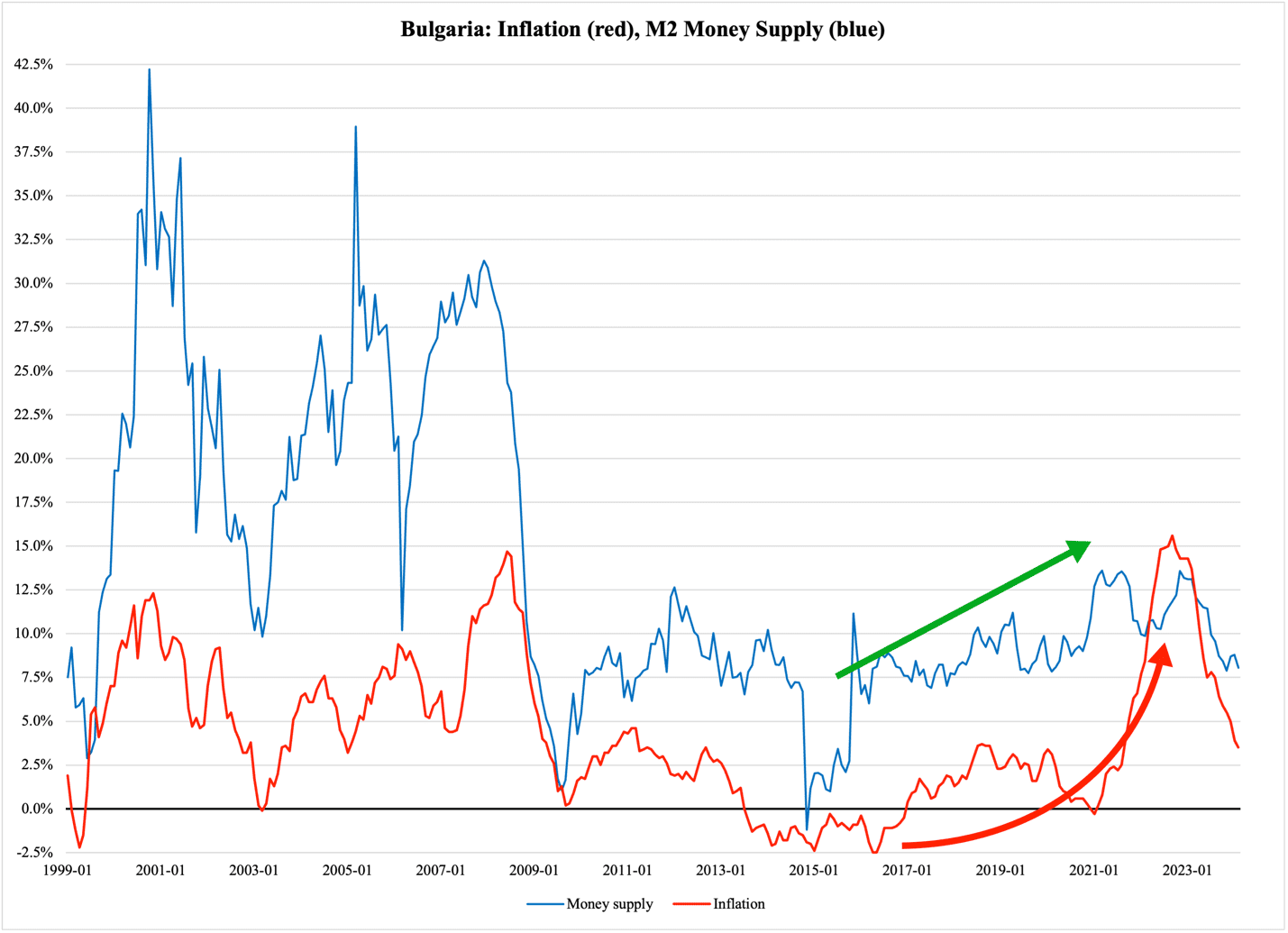

The first type of inflation is also known as ‘cost-push’ inflation, while textbooks refer to the second type as ‘demand-pull’ inflation. Neither type can cause any serious levels of inflation, but the third type can—monetary inflation. Just like the rest of Europe—as well as North America—Bulgaria experienced a sharp spike in monetary inflation in 2021 and 2022. As Figure 1 explains, there is a compelling correlation between the Bulgarian National Bank’s expansion of the money supply (blue line; measured as M2, for all you monetary nerds out there) and the rate of inflation (red):

Figure 1

After two episodes of very rapid monetary expansion prior to Bulgaria entering the EU, and one right around the 2006 EU accession, the growth rate in the M2 money supply fell to more tolerable levels in the early years of the 2010s. As the red function shows, the inflation rate followed suit: it hovered in the 8-12% range for ten years, then it fell to levels that are close to price stability.

Beginning in 2012, the Bulgarian National Bank gradually tightened its monetary policy: in 2014, the M2 grew by a modest 2.7%. Consequently, inflation became deflation with falling prices for 41 straight months, from August 2013 through December 2016.

Unfortunately, this period came to an end after the central bank returned to monetary expansionism: as the green arrow indicates, the growth rate of the M2 money supply accelerated from 8% in 2016 to just over 11% in 2022. This profligate money printing gradually translated into higher inflation, which topped out at 15.6% per annum in September 2022. After that, it slowly tapered off—as did the expansion rate of the money supply.

As of February 2024, consumer-price inflation in Bulgaria is 3.5%; the money supply rate had fallen to 8%.

The problem for Bulgaria with replacing the lev with the euro is that it is a fatal decision in terms of policy independence. Currently, the Bulgarian National Bank can choose to take the lev off its fixed exchange rate toward the euro and thereby regain full monetary-policy independence to fight inflation, should it be necessary to do so. Once inside the currency union, the decision to conduct anti-inflationary policy lies with the ECB headquarters in Frankfurt.

Fighting inflation is one reason to maintain monetary independence; as Hungary has shown, there are other compelling reasons as well. The drawbacks of joining the euro zone outweigh the advantages—of which, to be honest, I cannot find a single one of any substance.