The American economy has been remarkably resilient over the past year. Surprising many analysts, its gross domestic product, GDP, expanded at 2.95% per year, adjusted for inflation, in the first quarter of 2024, at the same rate as in the last quarter of 2023.

These are good rates, at least by comparison to the past 15 years. Remarkably, the U.S. economy has continued to beat expectations, and I would hate to be the one throwing cold water on a good economic outlook for the coming years. However, more and more signs suggest that we have at least reached the peak of this growth period.

To begin with, the economy actually did go through a bit of a ‘breather’—a milder and shorter economic slowdown than a recession—in the last three quarters of 2022. Back then, real GDP growth slowed to 1.8% in the second quarter, 1.9% in the third, and 0.5% in the fourth quarter. Consistent with economic theory, this brief ‘breather’ was followed by a return to decent growth numbers. It was only logical that this post-breather period would extend good growth numbers into 2024.

Another reason for the resiliency of the American economy is that it remains, fundamentally, a market-driven machine. Our governments, at all levels, really do try to throw gravel into the machinery, but so far it has not worked. On the contrary, there is anecdotal evidence that younger generations are turning to old-school entrepreneurship in higher numbers than the generation before them. International investors also remain very interested in putting their money into the U.S. economy.

These are examples of factors that continue to strengthen the dynamics and the resiliency of the U.S. economy. In doing so, they also contribute to longer, and eventually stronger growth periods. We are not going to return any time soon to the 1960s-1990s heydays with 4% real growth per year, but eventually, that may happen.

All in all, the U.S. economy is doing relatively well, and two sectors deserve the most credit for this.

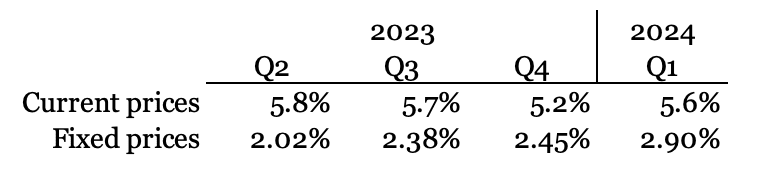

The first one is household spending, or private consumption, which is growing at an accelerating pace. These are inflation-adjusted figures:

- In Q2 of last year, 2.0%;

- In Q3, 2.4%;

- In Q4, 2.45%;

- In Q1 this year, 2.9%.

These are good numbers, explained in no small part by the decline in inflation. As price increases taper off, consumers get a chance to compensate for the ‘time lost’ to inflation:

- When prices rise rapidly, consumers concentrate their outlays on essential goods and services, cutting spending on desirable but less important items.

- When the economy emerges from the inflation episode, spending is redirected toward the less important items, such as replacing outdated computers, hiring someone to fix the roof on the house, or even going on that long-awaited vacation.

To this point, let us compare the numbers reported above to the same numbers including inflation, i.e., the increase in consumer spending at current prices:

Table 1

As reported in Table 1, the increase in current-price spending is holding steady in the 5.5% vicinity. This indicates that households in general have been able to cope with inflation (though not more than that). Therefore, with lower inflation, their growing money wages give them more room to spend money based on product quality and desirability—not just to fend off rapidly rising prices.

Since private consumption accounts for about 70% of all spending in the U.S. economy, the fact that households have weathered inflation helps keep the economy strong.

A less-welcome contribution comes from government. Its spending is inherently not a contribution to the free-market economy, but an intrusion on it. Therefore, the following numbers, while positive in the short run, are going to take a toll on the economy in the near future.

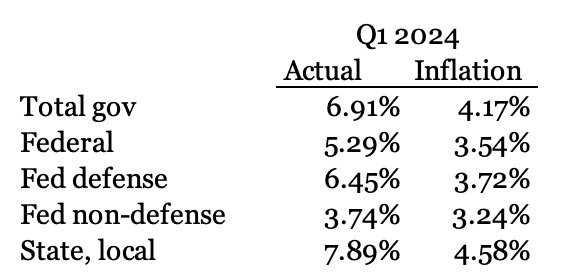

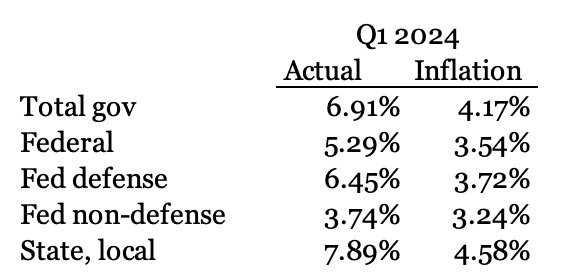

In the first quarter of this year, total outlays for federal, state, and local governments increased by 6.9% in current prices. (We use current prices here because we discuss taxes—which are paid in current prices.) Total economic activity, i.e., current-price GDP, increased by 5.8%. This means that government spending is outpacing its own tax base; the gross domestic product is the broadest possible definition of the base on which government can levy taxes.

No tax system actually covers all of GDP, but by comparing government spending to GDP in this way, we get the most favorable image possible of what chance government has of paying for its spending growth. When spending outpaces GDP, we know that even if government extended its taxes to every corner of the economy, it would still not get new revenue fast enough to pay for its growing spending.

The problem with government spending is that for most of the Biden administration, it has grown at inordinate levels. Some of it has been aimed at compensating government agencies for inflation, but that compensatory spending is no longer needed: inflation in the American economy peaked in the summer of 2022 at just over 9%; thanks to the Federal Reserve’s monetary tightening, it fell gradually and reached 3% a year later. Government faces a different set of inflation rates—every economic sector does—but those rates have also come down considerably.

Therefore, for the last year, there has been no reason to continue spending money through government for the purposes of inflationary compensation.

Given the global political situation, with military conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza, it makes sense to ramp up defense spending. It makes a lot less sense that states and local governments increase their spending faster than national defense, but this is exactly what happened in the first quarter of this year. In current prices,

- National defense outlays were 6.5% higher than a year earlier; meanwhile

- State and local government spending increased by 7.9%.

We have now had a series of quarters with problematically rapid growth in state and local government spending. In 2022, the average year-to-year growth rate was 8.2% in current prices; part of this is explainable by lingering pandemic stimulus programs. However, the average number for 2023 was 5.2%, which in itself is not a small figure.

To make matters worse, after falling to 4.1% in the third quarter, this spending category accelerated to 6.6% in the fourth quarter and, again, 7.9% in the first quarter this year.

What is happening at the state and local government levels? These figures are too high to be explained by the more or less inefficient infrastructure package that Congress passed earlier in the Biden presidency.

With the exception of national defense, there are no substantive reasons to let government spending grow at its current rates—let alone faster than GDP. If it were a matter of compensating for inflation, the spending numbers would have been considerably lower—they would still be high, but the difference is notable in Table 2. The inflation numbers reported are specific to government and its subsectors:

Table 2

With the fast-paced growth in government outlays at all levels comes the inevitability of budget shortfalls. This is first and foremost a federal problem, of course, but just because states are statutorily or constitutionally barred from running deficits, it does not mean that they actually do not run deficits.

With more government borrowing, interest rates remain elevated—in no small part because investors are increasingly worried about the risk of an eventual U.S. debt default (even a partial one). The elevated interest rates eventually become a problem for the private sector, where small businesses cannot afford loans to expand, and where households cut back on debt-driven consumption.

At this point, the rapid increase in government spending boomerangs back on the economy. The effect is going to be negative, quite possibly in the form of a deep recession.