On August 25th, big news broke in Germany:

🇩🇪 Merz: Germany Can’t Afford Its Universal Welfare System

— DD Geopolitics (@DD_Geopolitics) August 25, 2025

In a press statement, Friedrich Merz declared that Germany no longer has the economic capacity to sustain its universal welfare model.

“We cannot guarantee the financial sustainability of this system any longer.”… pic.twitter.com/qISqTOoUyB

The sensational nature of this announcement has apparently not sunk in with the German people, let alone its news media. In fact, reporting on this big story has been conspicuously sparse. There are a couple of notable exceptions, europeanconservative.com among them. The Daily Telegraph, an English news outlet, has a paywall-protected story, while Sputnik International and Russia Today have articles on Merz’s announcement.

On the western side of Europe, stories are few and far between. However, Deutsche Welle reports:

“The welfare state that we have today can no longer be financed with what we produce in the economy,” Merz said in the town of Osnabrück. The coalition partners had already agreed to reforming the social insurance system, which covers health insurance, pensions and unemployment benefits, due to rising costs and gaps in the federal budget.

In other words,

The cold, hard truth here is that Chancellor Merz has fiscally capitulated before the welfare state. Hopefully, he will draw the right conclusions from his surrender, though I am worried that he will take the convenient approach and blame it on current events. The X comment cited earlier does just that, pointing to “demographic aging, high immigration, and mounting debt obligations.”

Those factors are superficial in comparison to the root cause of Berlin’s fiscal surrender. The fact of the matter is that the German welfare state was doomed to fail already from the beginning. The root cause is far greater and much more serious than what the media seem to be aware of.

I addressed this root cause eleven years ago, when I predicted that the welfare state would take down Europe’s economies. In my book Industrial Poverty (Gower 2014),I explain in detail how the welfare state functions like a parasite on the private economy. The more blood it sucks out in the form of tax payments, the more it weakens its host. Likewise, the more entitlements the welfare state pays out, the more it pacifies the productive forces in the economy.

As the economy weakens, demand for welfare-state entitlements increases. This causes the welfare state to dispense more of the fiscal venom that pacifies the productive forces. In order to cover the cost of the increased doses of fiscal venom, government raises taxes, thus contributing at the other end to economic stagnation.

In his foreword to my book, Michael Tanner, at the time a senior fellow with the Cato Institute, summarized my analysis:

This structural crisis is comprised of three parts: a fiscally unsustainable welfare state, the high taxes needed to pay for it, and work-discouraging entitlements that depress labor force participation and lower economic activity.

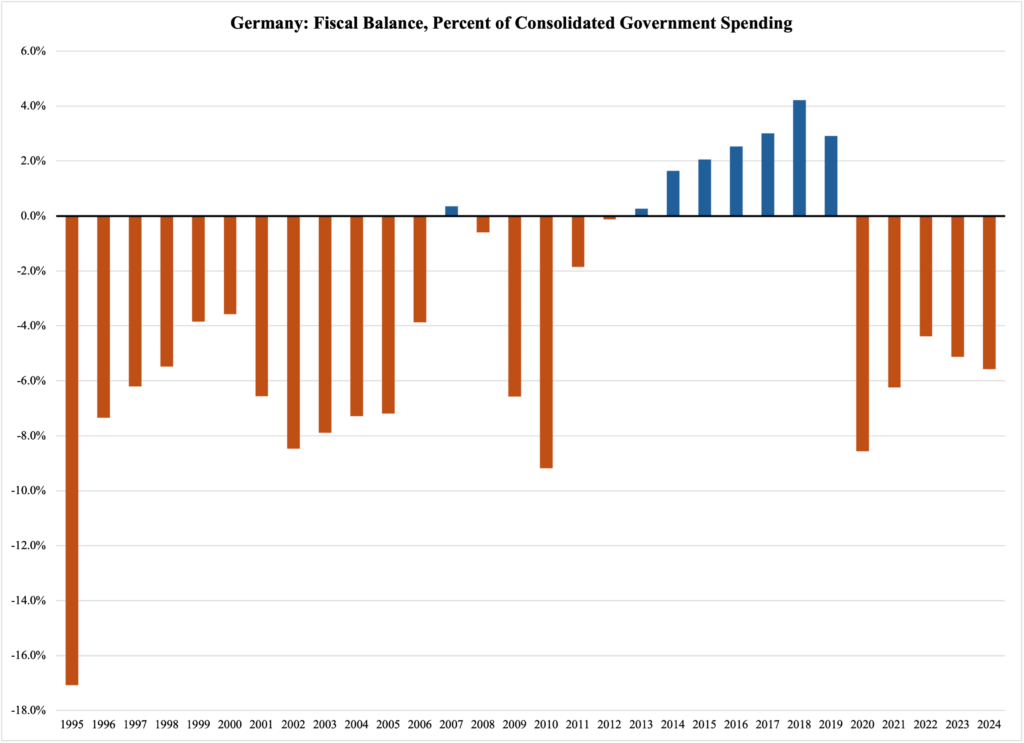

Germany is a prime example of this structural crisis. Over the past three decades, the consolidated public sector in Germany has run a budget surplus only in eight years:

Figure 1

The only reason why a long streak of deficits turned into a few years’ worth of surpluses is that Angela Merkel, who was chancellor from 2005 to 2021, relentlessly focused her domestic policy on raising taxes faster than spending increased. She also enforced a budget-balancing mechanism, which put her austerity measures on autopilot, year in and year out.

As I explain in my book, this is exactly the wrong policy to address the problem. It works as a small-dosage pump of more fiscal venom into the veins of the economy: higher taxes slow down economic growth, which makes more people dependent on more tax-paid entitlements, which drains yet more money from the public purse.

Over a period of 16 years, i.e., Merkel’s tenure as chancellor, this entrenches a structurally unsustainable welfare state so deep into the economy that it is almost impossible to get rid of—especially from a political viewpoint, which is precisely what the Germans are finding out now. According to the few news outlets that have covered this story, Chancellor Merz’s announcement likely marked the beginning of heightened tensions within his frail governing coalition.

It remains to be seen if the Social Democrats, SPD, can continue to govern Germany with Merz’s center-right Christian Democrats. The SPD has a long history of building and expanding the German welfare state, and for obvious reasons: the welfare state is socialist in nature, built on the principle of economic redistribution. Its purpose is to reduce differences in income, consumption, and wealth among the German people.

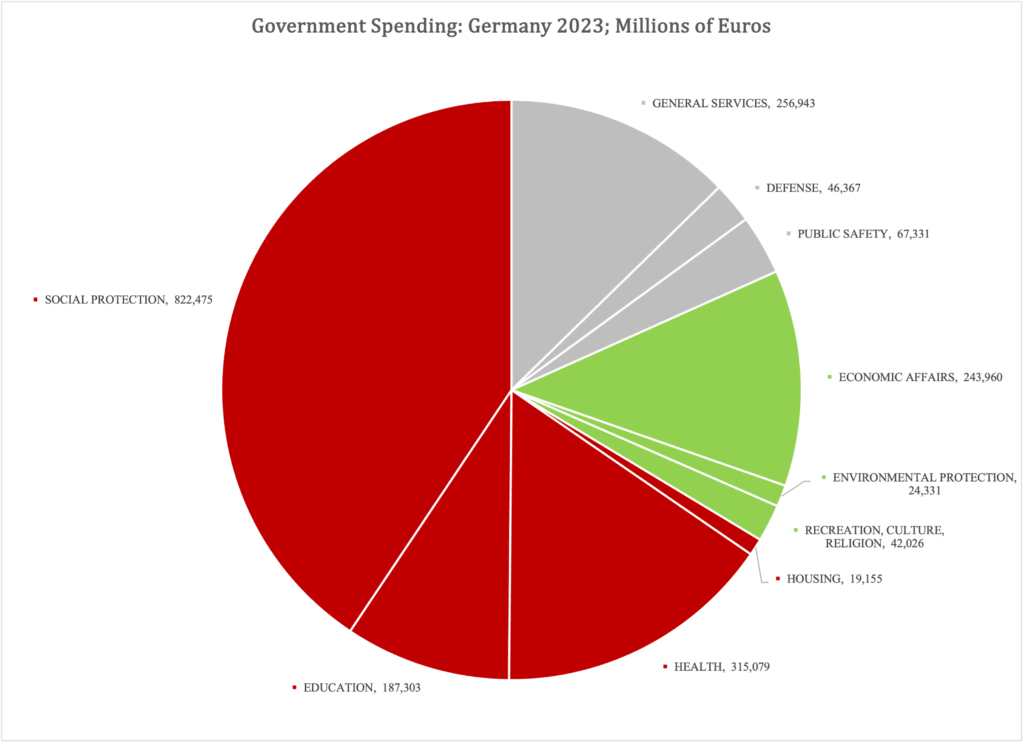

This purpose is manifested in the government’s fiscal priorities. Figure 2 reports the size of three blocks of government spending: the gray block represents core functions of government, including defense, public safety, and general services; the red block consists of welfare state programs; the green block covers non-essential programs that are not part of the welfare state.

Figure 2

Of the €2 trillion that the German government spent in 2023, two-thirds went to the welfare state. This share, which is slightly higher than the EU average, has been largely unchanged since the mid-1990s. This, in turn, is a testament to the high priority that German governments have given to the welfare state over a long time.

It also lays bare the root cause of the conflict that now threatens to open a rift in Merz’s coalition. But even more than that, the large welfare state is an institutional declaration of purpose: all the legislatures over all these years that have created, grown, funded, and done everything to preserve the ‘red’ spending programs in Figure 2 have done so because they have an explicit or implicit ideological preference for a large, redistributive welfare state.

The German welfare state works just as intended: the Gini coefficient, which measures income differences in an economy, is 17% lower after the welfare-state programs have worked their way through the economy. In other words, Germans are 17% ‘more equal’ in terms of disposable income.

This is a sizable impact. It is also the root cause of Chancellor Merz’s announcement that Germany can no longer afford this massive redistribution.

In so many words: democratic socialism in Germany is about to reach a dead end.

The big question is what the Germans will do instead. We will have plenty of reasons to return to that question. In the meantime, I expect other governments in other European countries to follow suit and put an end to their decades-long efforts to put democratic socialism to work. This opens a wide range of opportunities for the future, from disastrous attempts at salvaging what is unsalvageable to courageous experiments in the socially conservative direction that Hungary decided to go a decade and a half ago.