On Tuesday, October 14th, big economic news came out of Hungary. The Budapest Post reported:

Hungary has launched its largest-ever bond issuance denominated in Chinese yuan, known as a Panda bond, as part of its strategy to diversify financing sources and strengthen economic ties with China. The move reflects Budapest’s broader pivot toward non-Western capital markets amid tensions with the European Union.

According to Daily News Hungary, the National Economy Ministry wants to use the new funds as a contribution toward

building up liquid reserves, especially important amid global economic difficulties and large-scale uncertainty … The issue further cements Hungary’s presence on one of the world’s largest capital markets and strengthens the country’s cooperation with China, the ministry said. Because of an expanded circle of investors, the financing of Hungary’s state debt stands on a number of legs, boosting stability, it added.

As relayed by Hungary Today, the yields, or coupon interest rates, on the yuan-denominated loans are low, making this an affordable affair for Hungarian taxpayers:

The three-year bond, issued at RMB 4 billion (cc. €475 million), carried a coupon rate of 2.5%, while the five-year bond, issued at RMB 1 billion (cc. €119 million), had a coupon rate of 2.9%.

Given the generally tense relationship between China and most of the Western world, understandably, there can be some worry about EU member states borrowing money in the Chinese currency. Back in 2022, the BBC put the question on its edge, suggesting that some

countries are having to weigh up the rewards—and risks—of signing deals with China. Many governments are increasingly wary of so-called “debt traps”, where lenders—such as the Chinese state—can extract economic or political concessions if the country receiving investment cannot repay.

To begin with, the question of extracting “economic and political concessions” from defaulting debtors would not be new to China. In fact, it is only reasonable that a creditor—be it a national government or a private lender—asks a non-performing borrower to own up to his obligations in every way possible.

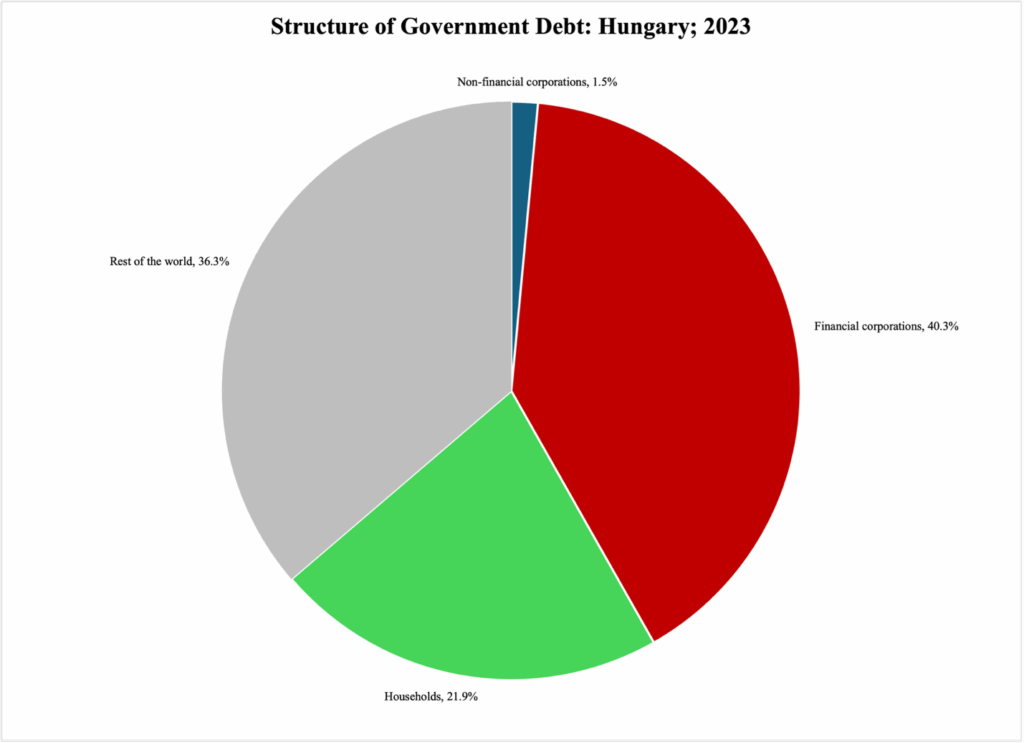

When it comes to Hungary, there is no need for such worries. To begin with, the Hungarian government is a highly reliable debtor with a credit rating that has remained stable for several years now. Furthermore, as I reported recently, the Hungarian government has an unusually well-diversified stock of sovereign debt. As reported in Figure 1, the household share of Hungary’s sovereign debt is 22%, the highest in Europe. With its own people owning more than one-fifth of its debt, the Hungarian government is in a great position to balance creditors—politically and economically—and thereby maintain a greater sense of independence than similarly indebted governments may have:

Figure 1

Although the newly issued yuan-denominated debt equals about 3% of total Hungarian sovereign debt, the sense of autonomy that comes with this type of borrowing is not to be underestimated. Precisely because the loan expands the Hungarian government’s exposure to new lenders, it avoids unhealthy creditor concentration.

In response to the point made by the BBC about possible political blackmail, it is important to recognize that any financial government-to-government relationship can become a politicized weapon. The EU has shown how it can use another type of financial relation, namely funds designated for its member states, as leverage in political skirmishes. There does not even have to be a real cause for conflict; trumped-up or made-up accusations are just as useful for financial, political, and other forms of coercion when Brussels wants to gain the upper hand against what it considers to be a non-conformist member state.

In a manner of speaking, by virtue of its EU membership, Hungary has already maxed out its exposure to the very political risks that are now being associated with its issuance of yuan-denominated debt instruments. It is also worth noting that the Chinese-aimed treasury bonds were not aimed at the Chinese government per se; the Chinese financial markets are rife with institutional investors looking for new assets to add to their portfolios.

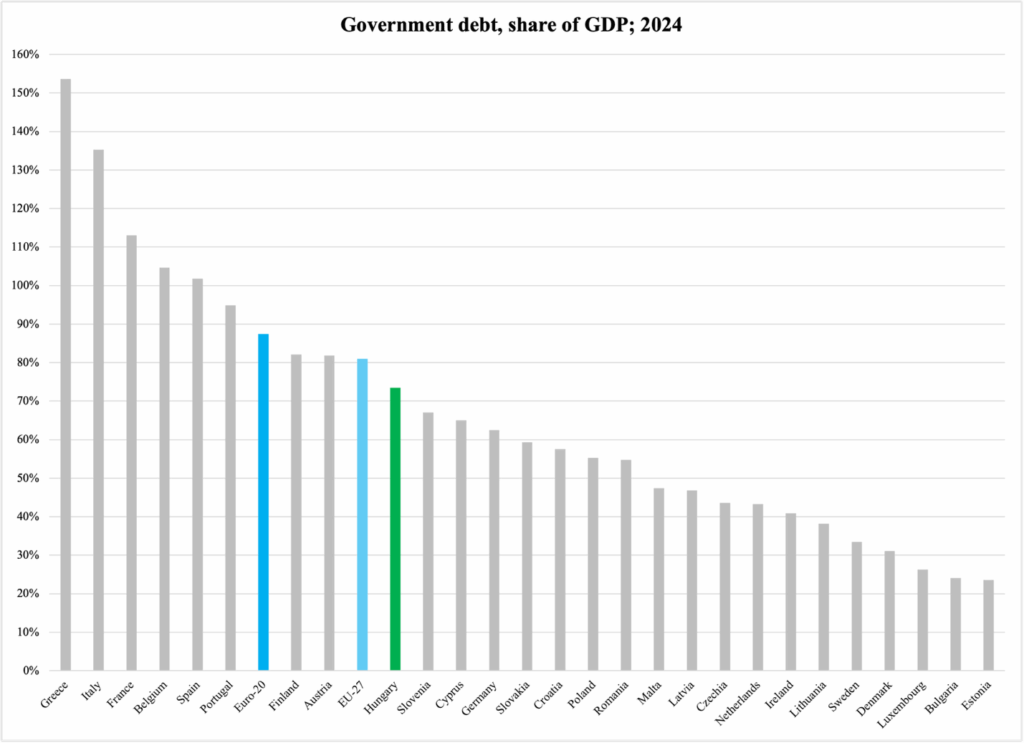

Beyond the understandable but unfounded skepticism about Hungarian government debt being contaminated by Chinese politics, there is a broader point to be made about the country’s government debt. Unlike most other EU member states, the Hungarian government is not near, or nearing, any kind of debt crisis. For starters, its debt-to-GDP ratio is lower than the EU average—and substantially lower than the euro zone average:

Figure 2

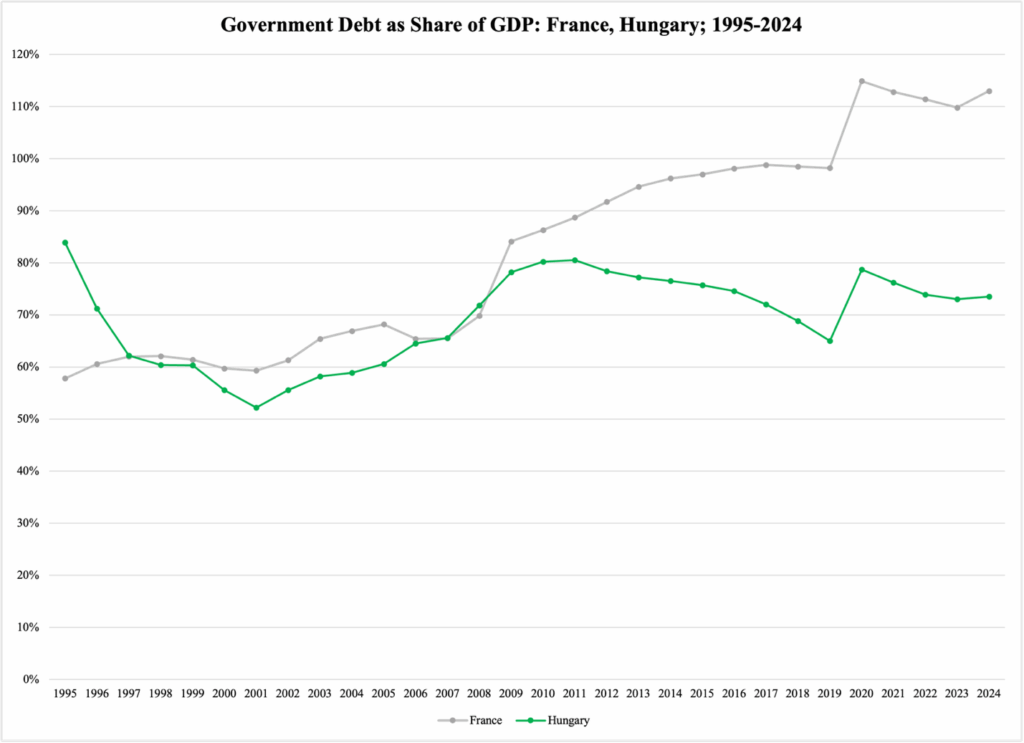

It gets better. Figure 3 reports the trend in Hungary’s debt-to-GDP ratio since 1995. Unlike some of the EU’s bigger members—France is included as an example—the Hungarian ratio has never reached crisis-inducing levels above 100% of GDP. In fairness, there was a risk for that in the first decade of this century, when the ratio shot up from just over 50% to 80%. However, since Fidesz formed its first government, the ratio has been stable; until the 2020 pandemic, it was even in mild decline:

Figure 3

With a debt-to-GDP ratio that is predictably parked below the EU and euro zone averages, there is no risk that Hungary would be hurled into a debt crisis. This vouches for further improvements in its credit rating (the two latest “negative outlook” markings notwithstanding) and for Hungary being welcomed back for more deals on global debt markets, including the Chinese. Given the prudence with which Prime Minister Orban’s government has managed its debt so far, the outlook is bright for future diversification of its creditor list.

The only caveat with loans in yuan is that the Chinese central bank in recent years has been fairly aggressive in pursuing an expansionary monetary policy. This has led to low interest rates—and low borrowing costs for Hungary—but it also raises the risk for future inflation. When inflation goes up, so do interest rates.

With that said, similar if not stronger risks exist for any issuance of debt in euro and in U.S. dollars. Unlike the Chinese central bank, the ECB and the Federal Reserve have proven that they can disregard all safety measures in monetary policy that are supposed to prevent monetarily driven inflation.

In short: if there are inflation-driven risks associated with Hungary’s yuan loans, those risks are higher for debt sold in euros and dollars.