Interest rates are on the rise across Europe. Mortgage loans, car loans, credit cards, checking overdrafts, and other forms of credit are getting more expensive. This is coming on top of more than a year of high inflation, making everyday life even more expensive for families and businesses alike.

And it is not just happening in Europe.

The American economy is experiencing interest-rate hikes across the board, with the Federal Reserve—the central bank—leading the charge. On February 1st, they raised their governing rate, a.k.a., the federal funds rate, by 50 basis points, or ‘half a percent.’ This puts the rate in a span of 4.5-4.75%.

The day after, the Bank of England raised its governing interest rate from 3.5% to 4%, and the Danish national bank hiked its four rates by 35 basis points to 2.1-2.25%. The European Central Bank raised its three key interest rates by 50 basis points, with a span from 2.5% to 3.25% going into effect on February 8th.

A week later, the Swedish central bank started applying its new 3% governing interest rate, up from 2.5%.

The Stagflation Threat

A standard answer to the question of why these rate hikes are happening would be that central banks are desperate to kill off inflation once and for all. But is that really necessary anymore? After all, inflation is in decline now, just as we have predicted. On January 19th, The European Conservative again was ahead of the curve in economic forecasting: we assessed that inflation in the euro zone had peaked and determined that from that point on, it would be declining. About two weeks later, Eurostat published its inflation flash estimate for January, confirming that our prediction was correct.

Good news as this may be, though, it is not good enough. Inflation remains a problem in Europe generally, and specifically in the countries that have not yet reached the definitive peak. Those who have not, have problems of varying degrees to tackle. Hungary, which currently has Europe’s highest inflation rate, does not have too much to worry about as its inflation is relatively easy to manage. The phenomenal economic growth in Hungary in recent years, with one of Europe’s strongest labor markets, is an underlying strength that protects the Hungarians from runaway inflation.

Other countries with inflation close to or above 20% per year—the Baltic States come to mind—have more to worry about. Their economies, though reasonably solid, have not performed nearly as well as the Hungarian economy has over the past several years. Therefore, they exemplify the risky scenario that makes high inflation such a threat: the combination of economic stagnation, specifically high unemployment, and high inflation.

We know this combination as ‘stagflation.’ It is a dangerous place for an economy to be: no new jobs are created, business investments are minimized to absolute necessities, and consumer spending gets stuck in a static loop. Colloquially speaking, nothing grows and nothing improves. Economic forecasts take on the color and excitement of a rainy-day outlook.

Europe is not yet in a bonafide state of stagflation, but the numbers on inflation and unemployment are pointing worryingly in that direction. Let us start with 2016, a year when economic conditions were ‘normal’ in the sense that price stability was combined with comparatively strong economic growth:

- The 13 EU member states with unemployment above 8% (12% on average) had a ‘negative inflation rate’ of -0.23%; this, of course, is also known as deflation;

- The 14 EU member states with an average unemployment rate below 8% (6.2% on average) had an inflation rate of 0.5%.

These are very small inflation numbers, but the difference between deflation and inflation is significant. They also contrast well against the same numbers for 2021:

- The 13 EU member states with the highest unemployment (8.7% on average) had an inflation rate of 2.5%;

- The 14 remaining member states (4.7% unemployment on average) had an inflation rate of 3.2%.

Inflation and Unemployment

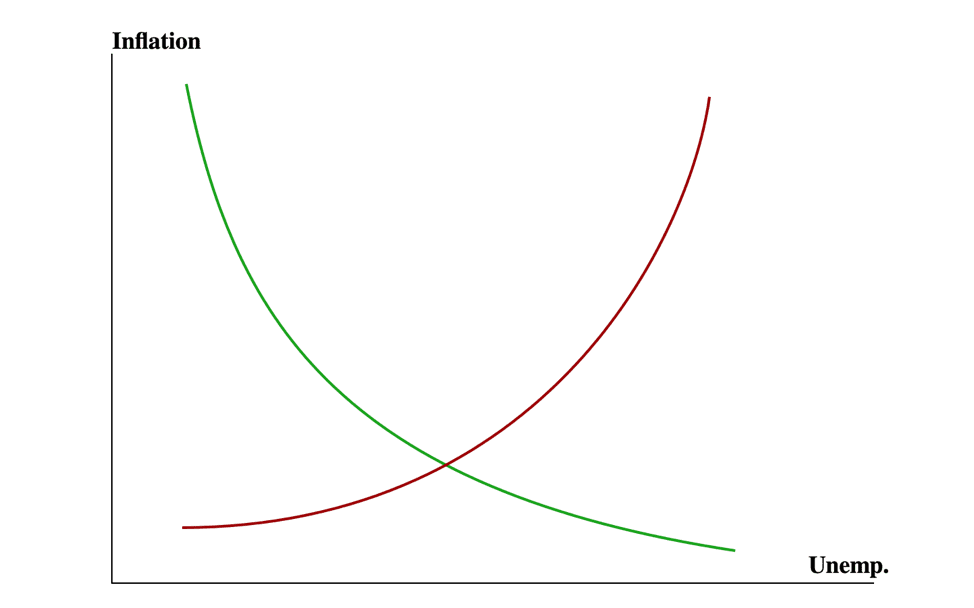

Numerically speaking, the difference is not very big between the two inflation rates in 2016, no more so than the difference in 2021. However, from an economic viewpoint the difference is significant; to see why, let us explore the good old Phillips curve. Invented as a statistical correlation by New Zealand economist A.W. Phillips in the 1950s, this curve has become an integrated part of standard macroeconomic theory. It compares two variables, inflation and unemployment, predicting that the relationship is negative under normal circumstances.

In Figure 1 below, this ‘normal’ Phillips curve is green. The numbers from 2016 reported above, are consistent with a negative, green curve. By contrast, when the economy is in a state of stagflation, the correlation between inflation and unemployment turns positive—as illustrated by the red function:

Figure 1

The aforementioned inflation and unemployment figures for 2021 do not show a positive Phillips curve, but they are close to a flat one. Theoretically, this is an intermediate state between the two curves in Figure 1; in practice, there is nothing that says that a flat curve has to fully tip over and become positive.

At the same time, there is nothing in economic theory that says the ‘full tip’ will not happen. The central bankers who are now raising interest rates are fully aware of the possibility of a full-fledged positive slope. Since this is the definition of stagflation, they should be worried.

If there is one state of economic activity we want to avoid, it is stagflation. Its destructive force is often underestimated in the economics literature, possibly because the industrialized world has seen such few episodes of it. The last major outbreak of stagflation took place just over 40 years ago.

There are several reasons why stagflation is bad, but the most important one is that it carries with it the seed of fundamental economic instability. In plain English: if stagflation sets roots in the economy, it will destroy the very fiber that keeps our economy manageable and predictable. The reason is its inversion of the relationship between prices and quantities.

On a normal day in our free-market economies, prices are kept stable by the interaction between supply and demand. When demand rises relative to supply, prices are pushed up until buyers decide that whatever is in high demand has become too expensive to be worthwhile. By contrast, when demand falls relative to supply, prices decline until buyers decide that the product in question is worth the money.

There are many reasons why swings in the balance between supply and demand cause price fluctuations: people’s incomes rise and fall; taxes go up and down; consumer preferences change; entrepreneurs invent new products or improve existing ones; and so on. However, regardless of what the reason is for prices to change, the interaction between supply and demand always brings price changes—whether inflationary or deflationary—to a halt.

The balancing mechanisms of the myriad of free markets in our economy aggregate into the Phillips curve. High demand, i.e., high levels of spending by consumers and businesses relative to the total supply of goods and services, results in low unemployment, and higher rates of inflation. Conversely, when spending declines and the economy is characterized by an excess supply of goods and services, there will also be an excess supply of labor, i.e., unemployment. This is when inflation is low or even negative, i.e., deflation.

When the economy swings between the two extremes on the green Phillips curve, we call it a business cycle. The top, at the inflation peak, is the growth period, when there are high levels of economic growth, low unemployment, and strong growth in household incomes. By contrast, the high unemployment end is a recession where jobs are scarce and incomes stagnant.

Free markets mitigate business cycles almost entirely on their own. It is very rare that a well-working economy without undue government interference is thrown out of the stable cycle between inflation and unemployment. When that happens, it is almost entirely the result of government intervention in the economy. While those interventions can look superficially different, they usually break down to excessive monetary expansion.

Opening for Economic Instability

A favorite motive for high levels of money printing is that government wants to use the money to fund entitlement benefits and other government programs. However, when looking at the risk of stagflation in Europe today, it is of less importance where the threat of high inflation comes from (though excessive money printing happens to be the reason). What matters is the fact that inflation is here, and that we must stop it from hooking up with high unemployment.

When it does, the market mechanisms that maintain economic stability—the green Phillips curve—cease to function. At the level of the individual market, the relationship between rising prices and the supply-demand balance is reversed: when there is not enough demand for a product and prices should fall, they rise instead. Despite the fact that consumers do not have enough money to buy, say, a pair of shoes, the prices of shoes go up.

Yes, this is counterintuitive, but that is precisely the point. Under the conditions that create stagflation, our sense of normalcy in the economy no longer applies. We know what normalcy looks like: it is represented by the green Phillips curve. Stagflation tosses normalcy out the door, and we eventually reach a point where we can no longer predict the future using the knowledge that we apply to economic normalcy.

In other words, predictability and confidence are replaced by uncertainty and pessimism. As I explained in December 2021, this leads businesses to gradually shorten the review periods for their prices. Sensing that inflation is on the rise and that their understanding of what is normal for the economy no longer applies, they start making changes to the prices of their products more often. This may seem irrational, but it is really the best instrument from a business perspective to try to secure a steady cash inflow.

From the other side of the market, the shorter price review periods appear as accelerating inflation. Every time businesses review their prices, they mark them up; the more often they do so, the faster inflation rises.

When the pace of price adjustments reaches a critical point, it turns inflation into a self-propelling phenomenon. Price increases become entirely independent of the activity level in the economy but since, at this point, inflation is so high it makes the ‘economic tomorrow’ virtually unpredictable, this state of economic affairs destroys the economic planning of both businesses and households. It is practically guaranteed that high inflation will be coupled with high unemployment.

In a word: stagflation.

Since prices are now set independently of what market conditions look like, the economy no longer has a leash on inflation. It can run away and become hundreds, even thousands of percent per year. Venezuela has had encounters with inflation in the millions of percent.

Nobody is predicting this kind of astronomical inflation in Europe, but—as mentioned earlier—it is also impossible to guarantee that this cannot happen. Even with moderate inflation rates, stagflation is the creator of systemic instability in the economy, and therefore of the conditions for runaway inflation rates.

This is why central bankers are well advised to tighten the money supply now, while they can still control inflation. There is no way around the fact that in doing so, they will create pain here and there in the economy. However, there are no painless options here:

- Either we take the upfront pain while we can still keep it manageable, and thereby avoid a protracted and deteriorating stagflation experience;

- Or we give ourselves some short-lived comfort and try to ignore the unmitigated economic disaster that—if not prevented—will happen within the next 12-18 months.

It is against our instinct as rational beings to accept a list of options where all are bad, but that is where we find ourselves. Either we live with high interest rates today, or we put our very prosperity in stagflation-driven jeopardy.