Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis delivers a speech during the European People’s Party (EPP) congress in Valencia, on April 30, 2025.

JOSÉ JORDAN / AFP

From 2009 to 2014, Greece was de facto ruled by the European Union, the European Central Bank, and the International Monetary Fund. During those years, the EU-ECB-IMF troika forced the Greek government to make extreme budget cuts and implement economically crippling tax hikes. Social welfare programs were cut by 50-90%, while the tax burden increased by 11 percentage points of GDP.

The austerity campaign was nothing short of economic warfare on Greece. In addition to wiping out one-quarter of the economy, the destructive austerity policies reached so deep into the very lives of Greek families that they even changed the demographic future of the country.

For ten years, since the end of the troika-led austerity campaign, the Greek people have lived with the consequences of unabated macroeconomic destruction. Now, the government in Athens has had enough: as we reported last week,

Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis presented an expanded and fully articulated demographic and economic agenda on Wednesday, November 26th, combining significant financial support for families, targeted tax reforms, and new incentives for young workers and entrepreneurs. In his remarks, the prime minister outlined what he described as Greece’s first comprehensive strategy to confront demographic decline. The government, he said, can allocate €1.76 billion in 2026 to support this strategy, adding that “the protection of the family is at the core of the government’s policy.”

It is about time. Greece is a nation in deep industrial poverty; in a manner of speaking, Prime Minister Mitsotakis has nothing left to lose. He might as well go for policies that heretofore have not been tried.

His focus on strengthening families and businesses put the odds of success on his side. A focus on those two pillars of a free, prosperous society means that the government’s spotlight has been redirected from where it was during the austerity years. Back in those days, the prime directive of all fiscal policy was to bring balance to the government budget. It was enforced with rigorous indifference to its disastrous consequences.

Before I offer my advice on Mitsotakis’ plan, I need to once again paint the picture of just how big of a macroeconomic destruction Greece underwent in the years of austerity. The damage done by the EU-ECB-IMF troika is one of the most serious examples of political cynicism in the free world.

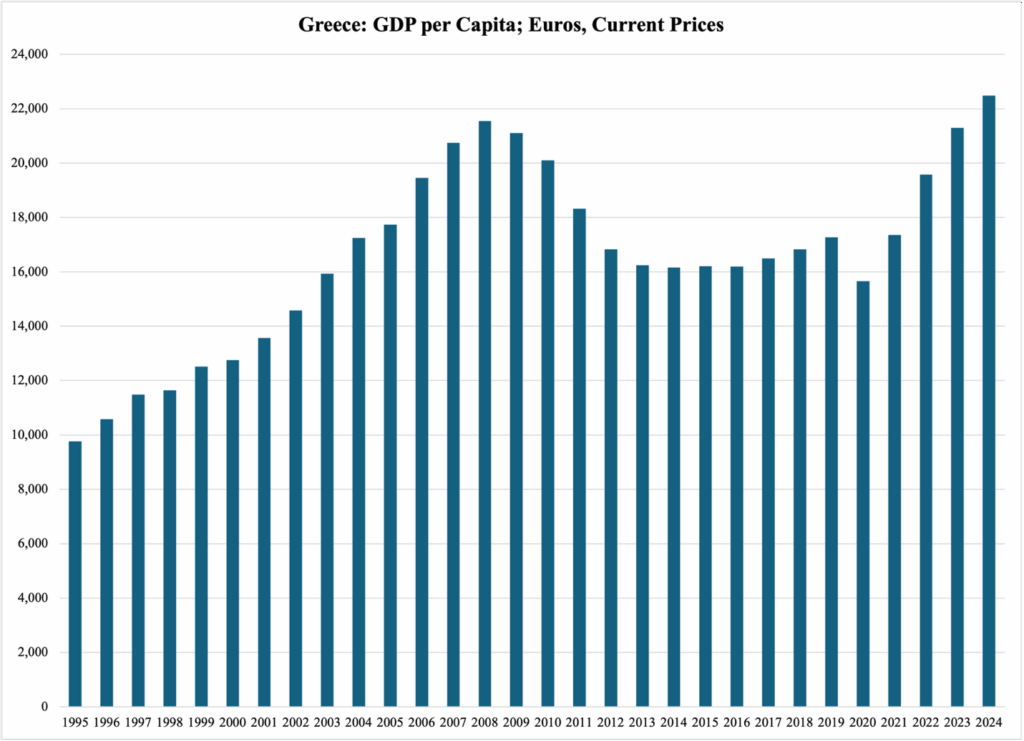

Figure 1 reports Greece’s GDP per capita from 1996 to 2024. The numbers are in current prices, i.e., inflation is not taken out of the numbers. This gives us the most accurate image possible of the Greek economy.

The decline that began in 2009 and continued to 2014—unique among industrialized nations in modern times—is entirely the result of fiscal austerity.

Figure 1

In 2008, the GDP per capita was €21,500; it was not until 2024 that the Greeks finally were able to exceed that level as the per capita size of their economy reached €22,480.

It took them 16 years to recover from what the EU, the ECB, and the IMF did to their country.

Let us also keep in mind that these are current-price figures. If we adjust them for inflation, the average Greek family still has not caught up with the standard of living it had in 2008.

There is a different way to understand the economic destruction illustrated in Figure 1. Suppose that GDP per capita had continued to grow at largely the same rate after 2008 as it did before that year. With adjustment for a normal recession in 2009 and for 2020 pandemic disruptions, then in 2024 the Greek GDP per capita would have been twice as big as it actually was.

This would have placed Greece in the same league as Finland or France.

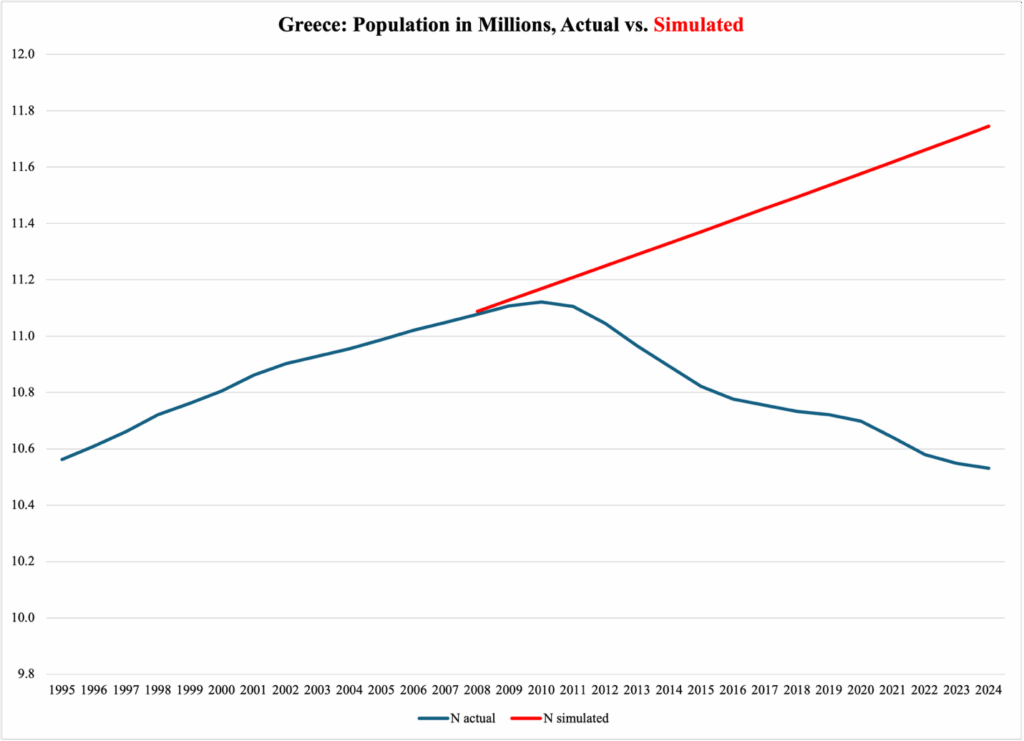

As a direct result of the austerity-driven economic implosion, Greece began losing population. Figure 2 compares the actual population trend since 1996 (dark blue) to a hypothetical trend if the pre-austerity population trend had continued (red).

Figure 2

The flip from population growth to population decline (black line) is frighteningly well correlated with the half-decade-long EU-led austerity campaign. If Greece had instead continued to evolve economically like a normal country, a simple extrapolation of the average population growth for 1995-2008 would have looked like the red line suggests. Today, instead of tallying 10.5 million people—the lowest number in 30 years—the Greek population would have been greater than 11.7 million.

Thanks to the Mitsotakis government, the future for Greece may be brightening up. The key element in the prime minister’s pro-family vision is a limited but targeted tax reform:

The government has the possibility to allocate for 2026, 1.76 billion euros and proposed the protection of the family, with tax relief depending on the number of children

Make no mistake: this is not some ad hoc ‘we have to start somewhere’ notion. It is an intelligent beginning of a family-promoting fiscal policy. Tax cuts, even if they come in the form of a selective “tax relief,” as in this case, or as permanent tax-rate reductions, improve the taxpayer’s purchasing power. More money is left in the pockets of, in this case, young families whose incomes are comparatively modest; their propensity to spend every euro is practically 100%. This means that the economy as a whole gets the highest possible boost from the measure.

Furthermore, a tax relief allows the taxpayer more economic flexibility than social benefit support from government. That flexibility is lost when government hands out benefits in kind: a child care subsidy can only be used for that very purpose; if a family finds ways to solve its child care needs other than putting their kids in daycare, then they lose the benefit altogether.

A cash benefit, especially in the form of a tax cut, comes with no such limits. Families can use the benefit and still organize their lives as they see fit. This greatly increases the chance that the money spent by government on the family-promoting measure will indeed have the desired effects—in this case, the formation, perpetuation, and growth of families.

With all that said, Greece will face a debate about using welfare state benefits to assist the tax cuts in the pursuit of their goal. Even if such policy measures were desirable on the same level as tax relief, there is an important reason why the government in Athens should refrain from any attempts to expand their welfare state—even if it is for such a desirable project as to support the nation’s families.

As mentioned earlier, the austerity campaign destroyed one-quarter of the Greek economy. In doing that, it also destroyed one-quarter of the government’s potential tax base. Governments don’t tax all economic activities, so they never tax the entire GDP. But since GDP includes all value created in the economy, it represents the government’s largest possible—or potential—tax base.

Whenever GDP expands, it becomes easier for a government to fund its spending because there is more economic activity to include in the actual tax base. By the same token, whenever GDP contracts, it becomes more difficult for government to raise enough taxes for its spending.

In the Greek case, austerity policies drastically reduced the size of the Greek government—but only on the spending side. Taxes went up with the same intensity as spending went down. However, since these policy measures reduced GDP, the remaining government spending ended up becoming more expensive to taxpayers.

In short: government required more out of every euro of income that the Greeks earned.

This increased cost for government applies to the welfare state as well:

In the 2010s, when the austerity policies went into effect with full force, the cost of the welfare state shot up to 31.2% of GDP.

These numbers may seem technical, but they have a very profound meaning: just to keep what is left of the welfare state alive, Greek taxpayers have to part with—on average—almost a third of whatever money they make. Then, with the cost of health care, education, social benefits, housing, and recreation programs covered, they have to pay for the rest of the government.

All in all, counting all forms of government revenue, Greek taxpayers have to part with roughly half of their earnings to balance the nation’s public finances. In this situation, an expansion of the welfare state—even for the noble purpose of supporting families—would be akin to a macroeconomic death wish.

There is, of course, the possibility of restructuring the welfare state within its current means so that its benefits can more efficiently target families. However, such a reform would require significant analysis and planning, as well as broad political support, in order to be successful over the long term. It could be done, and it should be done, but not until the first step—lower taxes for families—has gone into effect.