The American welfare state is a lot more generous with social benefits than many Europeans believe. Correspondingly, there is a widespread belief in Europe that the continent’s welfare states are generous and unwavering in their commitment to a citizenry in need.

Generally speaking, that belief is unwarranted. As I will explain in more detail in coming articles, the welfare states across Europe can be both stingy and expensive to their taxpayers.

As a warm-up, allow me to introduce a review of one particular component of the welfare state, namely the “social benefit” cluster of entitlements that governments across Europe gladly share with their citizens.

Superficially, those benefits look generous in many countries. A closer look, however, raises pertinent questions about the future of those benefits programs.

On August 11th, Euronews Business published a review of social benefits in Europe:

Family benefits play a key role in fighting poverty and promoting social inclusion. They help support households and are especially important in preventing child poverty. Across Europe, social security systems and family benefits vary hugely. One way to compare them is by looking at how much each country spends per person.

Although they do not give an explicit reference, their numbers are sourced from Eurostat’s ESSPROS database, which provides detailed information on various types of social benefits available to families—in the 27 EU member states as well as several non-members. For the sake of brevity, I am concentrating on the EU states here.

A key point in the Euronews story is that benefits vary a great deal between countries:

In the EU, expenditure on family benefits per person in 2022 ranged from €211 in Bulgaria to €3,789 in Luxembourg according to Eurostat. When EU candidates and European Free Trade Association (EFTA) countries are included, Albania offered the lowest benefits per person at just €48, closely followed by Turkey (€57) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (€59).

This sounds alarming: how can some countries be so stingy while others are overly generous?

The Euronews article does not address this question, but the ESSPROS database does. One of its additional pieces of information is the share of GDP in each country that the social benefits represent. Figure 1 has that information:

Figure 1

Social benefits are a big part of the entitlements that a welfare state pays out, but they are not the whole package. What makes them especially interesting to study is that they are focused specifically on the finances of the recipient family. In the vast majority of welfare states, the aim is economic redistribution, i.e., to elevate the personal finances of low-income families both in absolute terms and relative to families with higher incomes.

The larger the share of GDP that social benefits are, the more ambitious the redistribution efforts of the welfare state can be said to be. At the same time, there are other instruments that a government can use for the purposes of economic redistribution. One of them is the income tax, which is not accounted for in Figure 1. Almost all European countries have some kind of progressive personal income tax code, meaning that the percentage a person pays goes up with his income.

When combined with benefits, the progressive tax code can have a significant impact on the distribution of income in a country.

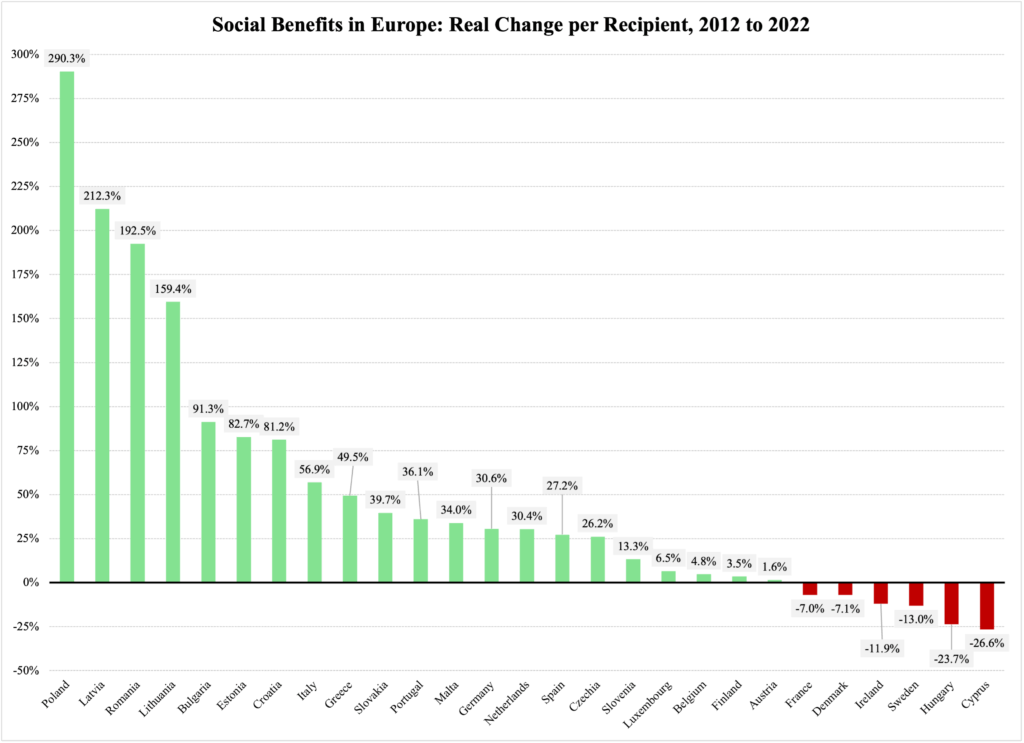

In their reporting of changes in social benefits, Euronews also points to major differences in how much those benefits have changed over the ten-year period from 2012 to 2022:

Among 32 countries, family benefits per person decreased in only two nations in euro terms, while increases varied significantly over the past 10 years. In the EU, the average rose from €566 in 2012 to €830 in 2022. This is a 47% increase, or €264. It declined by 5% (or -€130) in Norway and 18% (or -€62) in Cyprus. Part of this change may be due to exchange rate fluctuations. In percentage terms, Poland reported an unprecedented increase of 320%, followed by Latvia (245%), Romania (227%), and Lithuania (198%).

These are striking numbers, especially on the growth side. Even with our narrower focus on the 27 EU members, Euronews highlights the stark difference between an 18% decline in benefits in Cyprus and a 320% increase in Poland. Does this mean that the Polish government is more than three times as compassionate toward its citizens as the government in Cyprus?

No, it does not. The pattern emerging in terms of growth or decline in social benefits indicates that the ‘expanding’ countries are in the process of building up their welfare states. By contrast, countries that are shrinking their social benefit programs likely have a fiscal motive: their welfare states have outgrown their tax bases, leading to a policy response in the form of spending cuts.

Again, this is a hypothetical explanation of the vast benefits differences highlighted by the Euronews article. It was not within their scope to explain these differences; a comprehensive answer to such a question would require more space than both they and I have at our disposal. Nevertheless, the very reporting of differences in spending levels and in growth of social benefits is an invitation to a broader debate over why we even have those benefits in the first place.

However, there is one adjustment to the figures on growth in social benefits that Euronews could have done that would have elevated the value of their reporting: to adjust the social-benefit growth figures for inflation.

There is an important policy reason why this should always be part of any inquiry into long-term trends in welfare state spending. The benefits that the recipients are supposed to get, or be able to buy, are of course subject to the same inflation trends as other goods and services produced and sold in our economy. Since Europe has had a fairly difficult run-in with inflation in recent years, it is reasonable to ask how the growth in social benefits was actually affected by inflation.

As the green columns in Figure 2 report, most EU member states have grown their social benefit spending per recipient, even when inflation is taken into account. If a government’s policy is to provide its citizenry comprehensive social benefits in lieu of a path to self-determination, then Figure 2 depicts positive progress across Europe:

Figure 2

From the viewpoint of a traditional welfare state, the red columns in Figure 2 are an embarrassment. That would be the case as far as Denmark, France, and Sweden are concerned: over the ten-year period 2012-2022, their welfare states eroded the real value of their social benefits, shortchanging those who depend on government support.

The case of Hungary is different. Unlike the traditional socialist welfare states in Europe, the Hungarian one has been repurposed over the past 15 years. Instead of promoting economic egalitarianism through benefits for low-income families and punitive taxes on those who work, Hungary has a welfare state where the incentives are meant to encourage the formation, growth, and perpetuation of the family.

For this reason, social benefits of the traditional kind that emerged with the socialist welfare state in the early half of the last century are less important than other, family-promoting means.

More on the Hungarian welfare state in a coming article. The point here is that social benefits can decline in a country for very different reasons, and the ‘red side’ of Figure 2 should be reviewed with that point in mind.