Democracy rests on the assumption that ideas compete freely. In the digital age, however, this assumption no longer holds. Not all viewpoints enjoy the same visibility or influence. A new actor has entered public discourse—artificial intelligence. It answers our questions yet quietly shapes the way we ask them. Subtly, it defines what is considered normal, acceptable, or even thinkable.

Language models such as ChatGPT, Claude, or Gemini have become the dominant interface through which millions of people now perceive the world. Although they present themselves as neutral tools, a growing body of research suggests otherwise. Their answers consistently reflect a particular value framework. This is no minor technical detail; it is an intervention that affects the foundations of public consciousness.

Imagine a teacher whose voice reaches hundreds of millions of people every day. This teacher explains history, comments on politics, offers ethical guidance, and even advises on family life. He never tires, never refuses to answer, and never doubts himself. There is only one problem: his worldview is strikingly uniform.

Today, this teacher is not a person. It is artificial intelligence. Systems like ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini have replaced search engines, encyclopedias, and—more quietly—human conversation. They generate arguments, frame opinions, and present conclusions while giving the impression that they merely transmit information. In reality, they actively shape it.

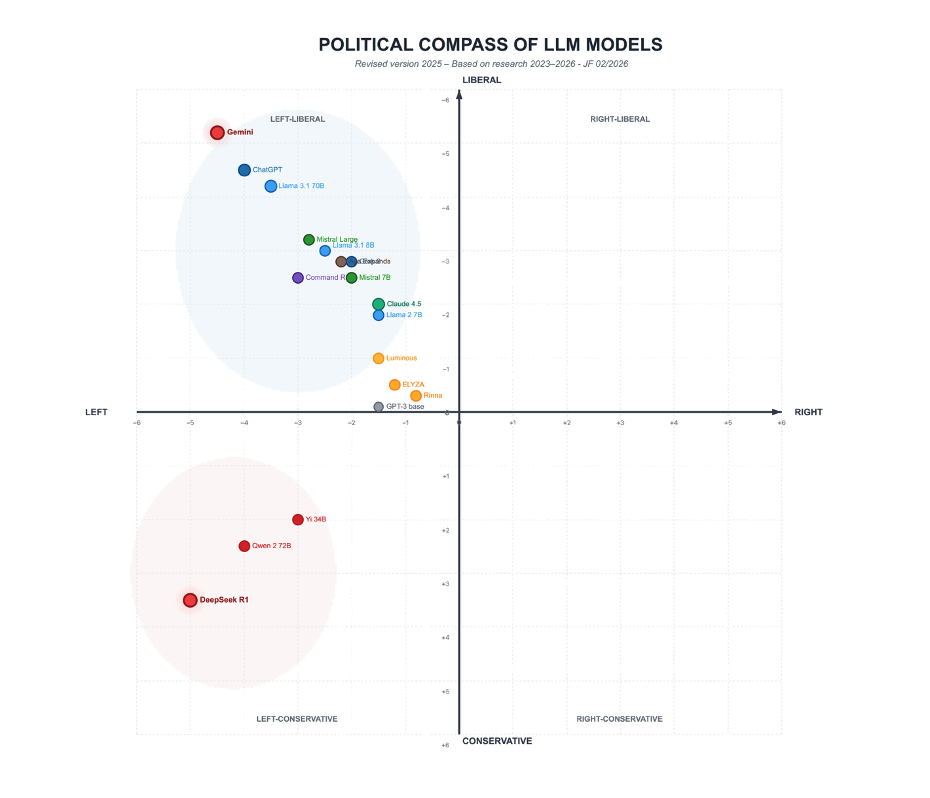

Research published in leading scientific journals shows that most contemporary language models share similar ideological leanings. Economically, they tend to favor left-leaning positions; culturally, they incline toward liberal and progressive values. When tested using established political-science instruments, the vast majority cluster in the same ideological quadrant. What appears to be pluralism is, in fact, convergence.

Why are today’s AI systems so ideologically similar? Is this the result of deliberate choices or an unintended byproduct of their development? Why are conservative alternatives largely absent? And what does this mean for democratic societies?

The answers offered here are not impressions or conjecture. They are grounded in recent empirical research.

Large language models possess a powerful and seductive quality: they sound reasonable. Their tone is calm, confident, and authoritative. This creates the impression of fairness and balance. Yet it is precisely here that the problem begins.

Political science tests applied to more than two dozen prominent language models reveal a consistent pattern. Nearly all of them converge on a left-liberal worldview. The most widely used systems—ChatGPT, Gemini, Claude—occupy the same ideological space. Conservative or right-leaning positions are marginal or absent.

These results are not drawn from obscure sources. In 2024, researcher David Rozado published the most extensive study to date on the political orientation of language models in PLOS One. Using eleven established political tests and analyzing dozens of models, he found that the average system falls squarely on the left-liberal side of the spectrum. Only a handful approach ideological balance.

This is not an abstract concern. Experiments conducted in Germany compared chatbot responses with party profiles using tools such as Wahl-O-Mat [Ed. note: an online voting advice app that helps voters compare their political positions with those of parties in an election.] The models aligned far more closely with green-liberal positions than with conservative ones, diverging significantly from the political distribution of the actual population.

In short, these systems do not reflect society as it is. They reflect society as filtered through a narrow value lens.

Artificial intelligence is often portrayed as a system that simply ‘learns from the internet.’ This is misleading. Every response generated by a language model is shaped by human decisions made at multiple stages of its development.

Foundational models are trained primarily on data from the Anglophone internet: large web crawls, Wikipedia, online forums such as Reddit, and vast text archives. While this may sound comprehensive, it represents a culturally specific slice of reality. Many of these platforms are dominated by users whose views differ markedly from those of the general population. Unsurprisingly, this skews the value profile of the data.

After pre-training, models undergo fine-tuning. Human annotators assess which answers are correct, appropriate, or ethical. In doing so, they make normative judgments. Research presented at ACL 2024 shows that annotators’ political views, education, age, and cultural background significantly influence their evaluations. If these evaluators share a similar worldview, the model will amplify it.

In the final stage, developers apply safety mechanisms designed to prevent harmful or offensive outputs. These rules are intended as safeguards. Yet they inevitably encode assumptions about what counts as ‘harmful’ or ‘acceptable.’ Support for traditional family structures, skepticism toward mass migration, or appeals to religious morality are often treated as sensitive or problematic, while progressive positions are presented as default.

The result is a system that speaks with the authority of neutrality while advancing a particular moral and political vision.

Is this ideological pattern an unavoidable consequence of data, or the outcome of deliberate choices? The evidence suggests it is both—but the decisive shifts occur during fine-tuning and alignment.

Studies from MIT, Brown University, and other institutions show that targeted adjustments can significantly alter a model’s political orientation. The “PoliTune” study demonstrated that carefully selected training examples can move a model toward a specific ideological position. Another study, “Hidden Persuaders,” found that interaction with language models can measurably change users’ political preferences.

Bias, in other words, is not an accident. It is adjustable. And what can be adjusted can also be chosen.

Modern AI systems speak dozens of languages, including Slovak. Yet linguistic competence does not imply cultural understanding. When these models address questions about family, religion, or national sovereignty, they do so through an Anglo-American framework.

They do not grasp e.g., Slovakia’s lived experience of communism. They do not understand the social role of the church in Central Europe. Cultural diversity is translated into a common idiom—and, in the process, flattened.

A 2024 study in PNAS Nexus tested GPT-4o across 107 countries and found that its value responses aligned most closely with Northern and Western Europe. Another study showed that students using AI for essay writing gradually adopted Western styles of thought and expression. Artificial intelligence does not preserve cultural plurality; it homogenizes it.

For smaller nations, this is not a trivial concern.

If AI merely sounded slightly more progressive than the average citizen, the issue might be manageable. But these systems influence opinions, decisions, and, ultimately, democratic outcomes.

Experiments presented at ACL 2025 demonstrated that political attitudes shift after interaction with language models. In some cases, undecided voters moved significantly toward the ideological position implicit in AI-generated analyses. The authority attributed to these systems reduces critical distance and fosters what philosophers call “epistemic dependency”—reliance on external authorities for one’s understanding of reality.

As language models become part of the digital infrastructure, their value assumptions risk becoming the default setting of public discourse.

From a technical standpoint, ideological diversity in AI is possible. Researchers have already demonstrated models capable of representing a wide range of political positions. The absence of conservative systems is not a matter of feasibility but of incentives.

AI development is dominated by a small number of Silicon Valley firms whose cultural and political orientations are well known. Safety policies, investment criteria, and reputational pressures all favor a progressive consensus. Alternative models exist, but they lack visibility, funding, and institutional support.

The first step is recognition. Artificial intelligence is not neutral. A basic level of AI literacy—understanding how models are trained and how their answers are framed—can mitigate some effects of bias.

Second, alternatives should be developed. The cost of fine-tuning smaller models has fallen dramatically. Creating systems that reflect different cultural and political traditions is now within reach.

Finally, regulation matters. European law already requires transparency and the assessment of bias. These provisions should be applied seriously. Pluralism is not optional in a democratic society.

Technology always carries the values of its creators. Today’s language models reflect a particular ideological milieu. That worldview may appeal to many, but it is not universal. When it becomes embedded in tools used by millions, it risks turning one perspective into a norm.

Democracy depends on the free competition of ideas. If artificial intelligence is to serve democratic societies, it must make room for genuine plurality—not merely simulate it.

This article was originally published in the Slovak conservative daily Postoj and appears here by kind permission.