The work of Dalmacio Negro Pavón reveals that politics cannot be understood without anthropology: the various conceptions of humanity throughout history are not mere theories but paradigms that have shaped the lives of peoples and conditioned political thought.

Nighttime.

Medium shot of an unpaved parking lot, bathed in the neon magenta light—deep pink—of an American diner. Dark green shadows fall on uneven rows of cars.

We hear the distant sound of customers and waiters. The closer rumble of an engine’s ignition.

A car backs up, breaking out of the uneven row of stationary vehicles. A dark green Chevrolet Impala, or a Lincoln Ford, or maybe something modern. A Lambo. More expensive, anyway, than the other cars.

Cut to a close-up of a calloused hand holding a symbol of Americana—a burger or a hotdog—putting it down, switching on the radio, and moving to the steering wheel. Dio’s “Rainbow in the Dark” starts playing.

The lighting and car give us visual cues that remind us of Nicolas Refn’s “Drive” before a close-up of eyes focused on the road ahead reveals the protagonist to the audience. Ryan Gosling.

The word ‘Ken’ appears in a 1970s Heavy Metal psychedelic calligraphy—

—just as Ronnie Dio pronounces the words,

No sign of the morning coming

You’ve been left on your own

Like a rainbow in the dark.

That’s my pitch.

Greta Gerwig’s Barbie, contrastingly decried as hyper-feminist propaganda and celebrated as thinly veiled conservative critique by the likes of Ben Shapiro and Michael Knowles respectively (in which context I would also highlight YouTuber Shoe on Head for emphasising how badly the movie fails to be coherently feminist, if feminist it is), should dispel the ambiguity with a sequel titled Ken.

Here, Barbie’s rejection of love interest Ken at the end of the first film, rather than a postmodern disavowal of the ‘happily ever after’ trope, is revealed as a necessary step in getting Ken to discover a genuine sense of masculinity, outgrowing prior feminist conditioning (following Knowles’ reading, or watching, of the movie).

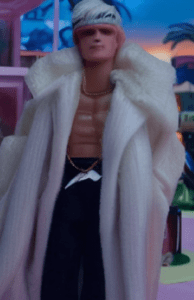

Mattel, for its part, should lean into Gosling’s portrayal and come up with a line of ‘Chad Ken’ action figures (emphatically not ‘dolls,’ if little boys are to be marketed to):

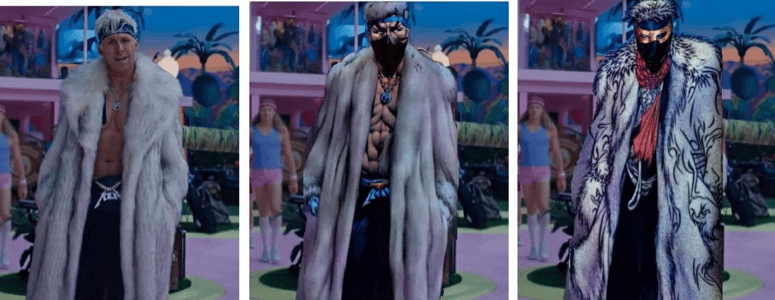

With potential for a line of Frank Frazetta-inspired comic-book spin-offs:

Turning to the movie itself, like the many films from the 2000s-era its pacing and humour hearken back to, Barbie presents us with an imaginary realm we may identify as that domain which in folklore is accessible to fairies or jinn—spirit folk—but which is also the province of human thoughts and dreams, with these taking a pseudo-physical form there (Neverland in Peter Pan, Fantastica in the Never-Ending Story, etc).

Essentially, we are dealing with the human collective unconscious—and it would make sense if, today, a certain region of that collective unconscious were to consist of objectified (but ‘empowered’) ‘girl boss’ figures and hapless male ‘simps.’ Such is BarbieLand.

The pathological relation between genders in this pink dystopia renders her denizens castrati, beings without private parts and unable to reproduce. It is a sterile place. The audience learns this at the end of the film, when it is revealed that the main change undergone by Margot Robbie’s Barbie character in entering our world is that she receives a fully developed anatomy, including a reproductive system.

Indeed, as Knowles points out, the movie starts off by showing little girls destroying baby dolls, which are to be replaced by Barbies as objects of play, and a little later we are told that the ‘pregnant Barbie’ doll was discontinued. There is no reproduction in BarbieLand.

It further critiques feminism by showing the restoration of BarbieLand’s gender hierarchy.

We may interpret those entities abiding in such a realm and wanting to enter the real world as human potentials, suppressed aspects of consciousness trying—legitimately or not—to affect people’s waking minds.

A Barbie that chooses to leave her female-run home-world and become real, therefore, is abandoning its ideal-type feminism, and a Ken who self-exiles from that land would, likewise, be choosing to discover himself as a man.

Of course, the obvious reading of the movie is that it thinks it’s showing us what our culture is like but in reverse: critiquing the real-world patriarchy through an imaginary dystopian feminist society. For my part, I don’t agree that a coherent conservative critique of feminism was necessarily intended. Inconsistencies in the worldview itself and waning commitment to its premises (partly owing to the palpably jaded mood now prevalent among Western culture-makers) may be responsible for punctual criticisms of feminism making it into the script.

It does afford a good opportunity for ‘culture hacking,’ in any case, and a meme Ken sequel has potential to steal the film’s cultural thunder.