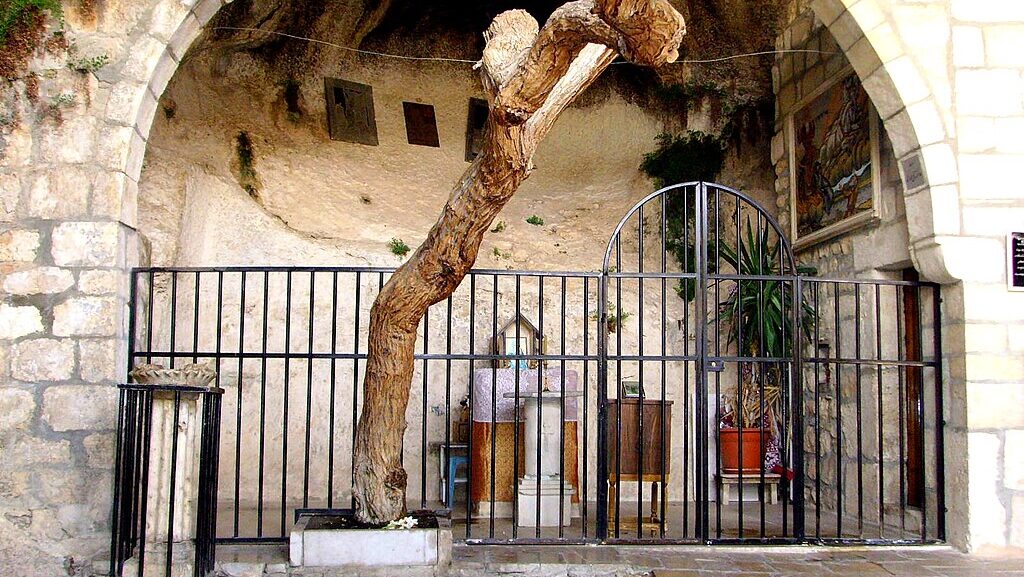

The Mar Takla Monastery in Maaloula, Syria, is a Greek Orthodox convent dedicated to Saint Thecla, a follower of Saint Paul.

Effi Schweizer, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

The Rum, a distinct Syrian Christian community with roots in the Eastern Roman (Byzantine) Empire and the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch, have endured centuries of upheaval while preserving their faith and identity. In this interview with europeanconservative.com’s Rafael Pinto Borges, a member of the Rum community shares insights into their historical significance, cultural resilience, and the challenges they face in post-Assad Syria. The interviewee’s identity is withheld for safety reasons.

The Rum, encompassing both Rum Orthodox and Rum Catholic (Melkite) communities, form the backbone of the Antiochian Greek Orthodox Church, with its patriarchal seat in Damascus. Historically, the Rum Church has been the dominant Christian institution west of the Euphrates in Syria, while the Syriac Orthodox Church, an Oriental Orthodox denomination, has held sway east of the river, extending into western Iraq. The Rum trace their origins to the Byzantine Empire, where their identity was shaped by the Greek-speaking Christian culture of the Eastern Roman world. This heritage, tied to the early Church Fathers and the apostolic traditions of Antioch, has defined their liturgical and cultural distinctiveness for centuries.

The resilience of the Rum community is remarkable, given the region’s history of persecution and instability. Our identity has been forged in the crucible of sacred lands—those of St. Paul and countless saints and Church Fathers. This spiritual legacy, combined with a distinct cultural identity, has anchored us through generations of adversity. Persecution, far from eroding our faith, has often strengthened our resolve. When faced with violence or exile for being Rum, we cling even more fiercely to our traditions and beliefs, embracing our identity as a badge of survival.

The narrative of the Assad regime—both Hafez and Bashar—as protectors of Christians is a distortion. While they projected an image of safeguarding minorities, their policies inflicted significant harm on the Rum. Under Hafez, economic attacks targeted Rum families, particularly landowners and farmers, contributing to the first sharp decline in our population. The regime’s actions extended beyond Syria, with ties to the assassination of Lebanese Christian President Bachir Gemayel in 1982. Since 2019, Bashar’s security apparatus, often led by his wife Asma, intensified persecution, arbitrarily detaining Rum, Syriac, and Armenian men—initially targeting jewelers and businessmen under pretexts like “dealing in dollars,” but later ensnaring professionals like doctors and lawyers. Ransoms of $150,000 were demanded for their release. I personally know of 17 family members of mine jailed without cause, none of whom had committed any crime.

The initial months following Assad’s fall were marked by uncertainty and fear. While some Christmas celebrations, including traditional Scout processions, resumed, they were subdued compared to previous years. After two months, religious life began to stabilize, but this fragile normalcy was shattered by sectarian violence, including massacres on the Syrian coast, attacks on the Druze, and the suicide bombing of St. Elias Hospital. These events prompted many, including my own family, to avoid church attendance temporarily out of fear for their safety.

The Rum face multifaceted threats. The influx of populations unfamiliar with our customs has led to attempts to impose restrictive norms, such as dress codes, gender segregation, and bans on public religious processions. More alarmingly, we face targeted violence for being labeled “infidels” due to our faith. Economic exclusion is another pressing issue, as contracts and jobs are increasingly reserved for those aligned with the ruling authorities’ sect, marginalizing Christians. These challenges threaten both our physical security and our ability to thrive economically and culturally.

There is profound skepticism within the Rum community toward HTS and Ahmed al-Sharaa’s assurances. Not a single person I know—despite my extensive connections—trusts their pledges to protect minorities. HTS’s historical ties to al-Qaeda and its record of extremism fuel this distrust, rendering their promises hollow in the eyes of the Rum.

The drastic decline in Syria’s Christian population has deepened the Rum’s sense of insecurity, a trend that began under Hafez al-Assad and has accelerated under the current transitional government. However, culturally, the fall of the Assads has lifted the oppressive cloud of enforced Arabism. Many Rum are now reconnecting with their Hellenic heritage, seeking to revive and preserve their distinct identity. This cultural resurgence offers hope, even as security concerns persist.

The Rum have faced unimaginable trials, yet our faith endures. I vividly recall the 2013 kidnapping of 13 Rum nuns from the Maaloula monastery, a sacred site of our community. During the civil war, indiscriminate violence struck our neighborhoods: rockets fell on homes, churches, and schools. The shelling of the Fatima Church in Damascus’s Christian Quarter claimed the life of a young girl, Rita, a friend of mine. The Al Noor Catholic School and Al Thawra Sports Club in Damascus were also bombed, the latter claiming my best friend’s life while I was present. These are but a few of the countless stories of loss and resilience that define the Rum experience.

Aramaic remains a living language in the Rum village of Maaloula, a testament to our linguistic heritage, though its use is limited. Koine Greek, however, was lost during the Ottoman era when its teaching was outlawed, and it has not been revived. These linguistic traditions, alongside our Aramaic-based liturgy, are central to our identity, anchoring us to our apostolic roots. Preserving them in today’s unstable context is challenging, yet they remain a vital link to our past and a source of communal pride.

For the Rum, Turkey is a historical adversary, responsible for the deaths of millions of our Greek and Christian ancestors. No Rum trusts Turkey or its proxies, including HTS. In Aleppo and Latakia, where Christian communities are significant, Turkey’s influence raises fears of increased marginalization and violence. The long-term impact remains uncertain, but the historical precedent fuels deep apprehension.

The international community must prioritize political representation for Syrian Christians and protect our communities from radical groups. This includes ensuring our quarters and villages remain safe havens for worship and cultural expression. Unfortunately, the international response has so far been inadequate, failing to curb the rising tide of sectarian violence and exclusion.

The prevailing sentiment among the Rum is one of exhaustion and disillusionment. Many, myself included, know countless individuals whose primary goal is to leave Syria permanently. The dream of a pluralistic society where our identity can thrive feels increasingly unattainable under the shadow of Islamist governance. The idea of a partitioned Alawi-Christian state in Latakia is appealing in theory, as it promises a safe haven, but it remains a distant concept. Even if realized, it would likely provoke endless conflict with those who claim the land as their own. For now, the Rum brace for further challenges, holding fast to their faith and heritage amidst an uncertain future.