AS Photography on Pexels

For decades, access to housing has been the primary stepping stone to personal, family, and social stability in Europe. Today, for millions of citizens, that step has turned into a wall.

Home prices are not only continuing to rise; they are doing so at a pace increasingly disconnected from real incomes, making it virtually impossible for the average citizen to buy—or even rent—a decent home without taking on lifelong debt or giving up any real prospect of independence.

What is most worrying is not just the scale of the problem, but the political normalisation of this drift. In its priorities for 2026, the European Union went so far as to consider the housing problem “over” less than a year after Ursula von der Leyen took office. Official data, however, tells a very different story.

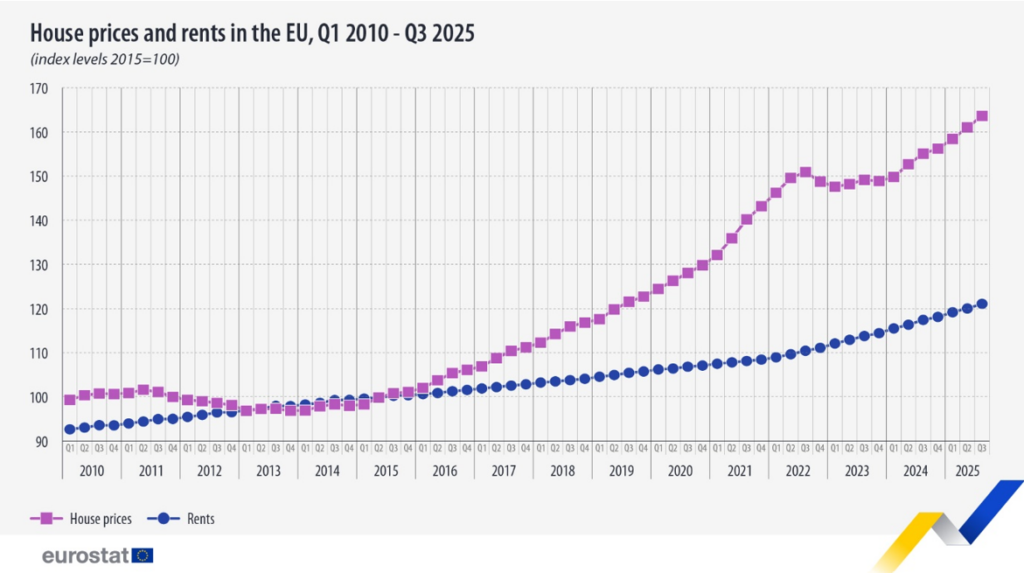

According to the latest figures published by Eurostat, housing costs continued to rise across the EU in the third quarter of 2025. Compared to the same period a year earlier, purchase prices increased by 5.5% and rents by 3.1%. Even quarterly, far from correcting, the market continued to tighten.

Since 2015, buying a home in the EU has become 63.6 % more expensive, while rents have risen by 21.1 %.

These increases have not been matched by equivalent wage growth. The result is a structural mismatch between the cost of living under a roof and what working people actually earn.

The core issue is not simply that housing is expensive, but that it has become wildly disproportionate to household incomes. While real wages stagnate or lose purchasing power due to inflation, housing absorbs an ever-growing share of household budgets. In many European capitals, renting a modest flat already requires more than 40% of the average net salary—an amount incompatible with any notion of economic stability.

Far from being treated as an anomaly, this situation is increasingly presented in some political circles as a “new way of life.”

This is where the narrative comes in. Unable—or unwilling—to tackle the root causes of the crisis, European institutions and progressive parties are trying to sell as a cultural choice what is in reality an economic imposition: the rise of “co-living,” permanent flat-sharing, and the abandonment of homeownership.

Several factors compound this structural pressure and are rarely addressed honestly. Mass immigration, concentrated in large urban centres, immediately increases housing demand without a corresponding rise in supply. At the same time, the proliferation of short-term tourist rentals has removed hundreds of thousands of homes from the residential market, further driving up prices.

The European Commission itself acknowledges that around 1.6 million housing units are built each year, when at least two million would be needed simply to meet demand. This shortfall accumulates year after year, while construction costs have risen by 56% since 2010.

Faced with the evidence, Brussels has reacted by creating a new commissioner post, dedicated to energy and housing matters, and by unveiling the first EU-wide “affordable” housing plan. But the EU is arriving late and with limited powers. Most key decisions remain in the hands of member states, while the European plan relies on adding 650,000 new homes per year—a figure clearly insufficient given the scale of the problem.

Moreover, the approach continues to prioritise administrative fixes and political narratives, without realistically addressing demographic pressure, legal certainty around property rights, or the impact of certain migration and regulatory policies.

In countries such as Spain, current laws make it extremely difficult to evict squatters. What was once rare and exceptional is on track to become increasingly normalised as more people are pushed out of the affordable housing market. By contrast, Italy under Giorgia Meloni has responded to illegal occupancy forcefully with its recently adopted security law.

Housing has become the ultimate barometer of Europe’s economic and social failure. When full-time work is no longer enough to secure a home, something fundamental has broken. Normalising this reality under comforting labels does not make it fairer or more sustainable.

The World Economic Forum’s infamous slogan—“you will own nothing and be happy”—now seems closer than ever to becoming reality.