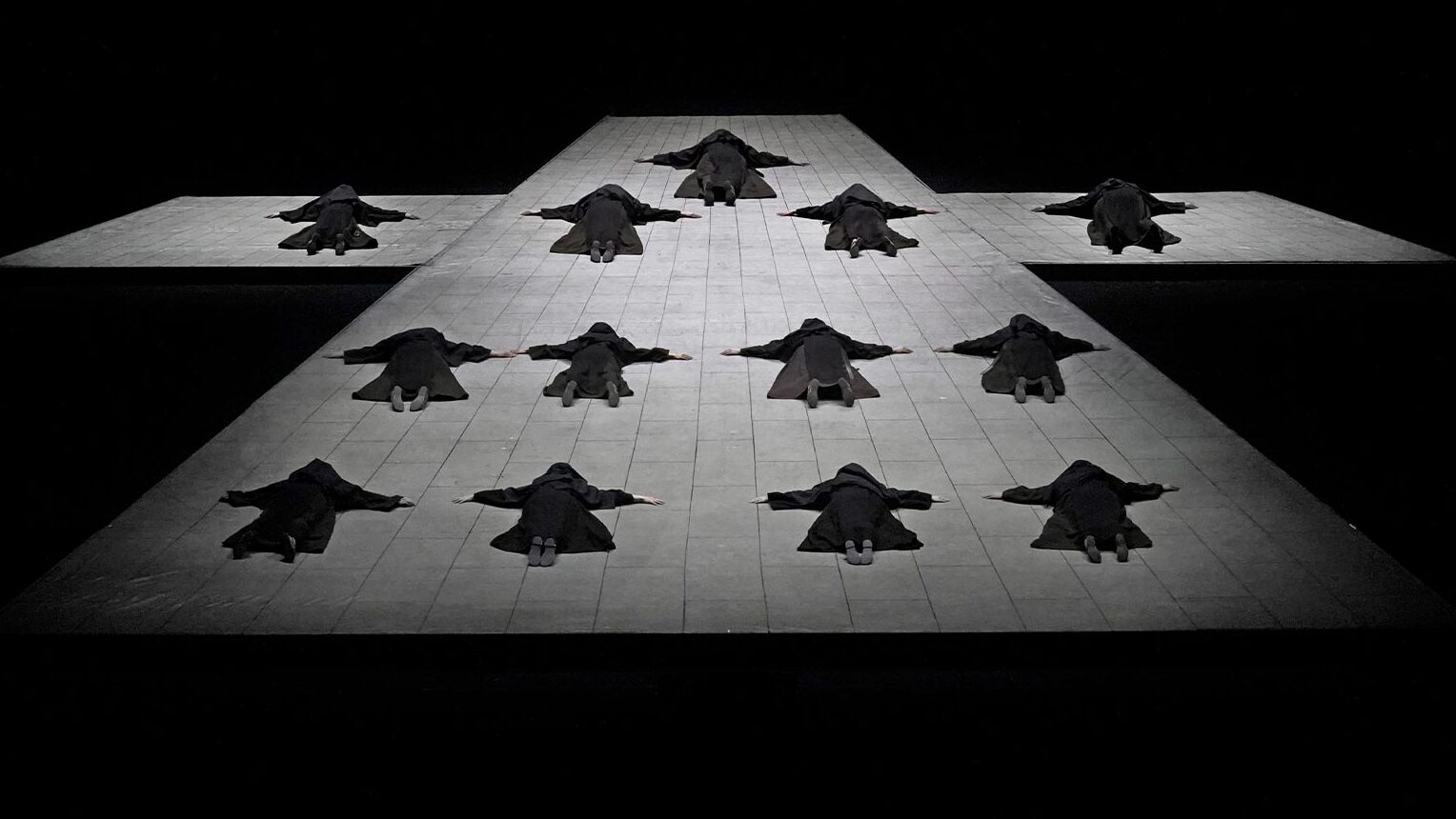

Photo: Metropolitan Opera

Bedeviled by low box office receipts, poor management, and an audience escaping to Florida, New York’s Metropolitan Opera has resolved to present more “contemporary” works, including one new work in that category on every season opening night for the foreseeable future. The definition of ‘contemporary’ seems to be works composed in the last 20 to 25 years, but this revival of Francis Poulenc’s meditation on faith and endurance, which had its world premiere in 1957, definitely drew in audiences big enough to make a dent in the Met’s mounting financial difficulties.

Poulenc emerged within the post-World War I generation of French modernist composers who rejected the Romantic idiom that had dominated Western music for more than a century before they came along in the 1920s. One of “Les Six”—a collection of six young composers (the other five were Darius Milhaud, Arthur Honegger, Georges Auric, Germaine Tailleferre, and Louis Durey) who sought to break the old barriers—Poulenc was especially drawn to neoclassicism and excelled in creating art songs still performed in recital. After a friend’s death in a freak accident in 1936, however, he embraced his family’s Catholic piety and began to adhere to a more traditional compositional style without altogether abandoning modernist innovation. “You must forgive my Carmelites. It seems they can only sing tonal music,” Poulenc remarked, acknowledging artistic debts to Verdi, Mussorgsky, and Debussy that are readily noticeable in his fluent score.

In the 1950s, Poulenc suffered further from the painful cancer-induced death of his lover as well as a profound sense of spiritual commotion over the travails of World War II and its legacies of horror, collaboration, and resistance. A commission from Milan’s La Scala gave him the opportunity to explore his faith and its trials in what would turn out to be his greatest work. The commission was originally to create a ballet on the religious themes of a play by the French Catholic writer Georges Bernanos, a work that had begun life as a screenplay for a film but was not produced before Bernanos’s death in 1948 due to reservations about its suitability for screen adaptation. The film nevertheless appeared in 1960, and a second, made-for-television film was produced in 1984 with more of Bernanos’s original lines. In the meantime, the screenplay’s adaptation for drama, called Dialogues of the Carmelites, was a smash hit stage play across Western Europe.

Bernanos’s inspiration was the martyrdom of 16 members of the French Carmelite order on July 17, 1794, at the height of revolutionary France’s Great Terror. Eleven of the victims were choir nuns, three were lay sisters, and two were tertiaries, though in Poulenc’s opera all are nuns. In the course of the French revolutionary years, the Carmelites were forced to surrender their independence as an order, they had their property seized, and went underground to survive. They managed to endure in hiding until early in 1794, when they were apprehended, found in possession of correspondence critical of the revolution, and imprisoned in a former religious house near their convent in Compiègne. Later, they were transferred to Paris’s infamous Conciergerie prison. They were tried without legal counsel, due process, or any strict requirement of evidence and sentenced to death by guillotine. As a tumbril carried them across Paris, they sang hymns, including a Salve Regina that Poulenc incorporated as his opera’s devastating finale. As they mounted the scaffold, they requested permission to die from their Mother Superior (who was the last to be executed), forgave their executioners, and sang not the Salve Regina, as they do in the opera, but Psalm 116, Laudate Dominum. The extraordinary dignity of their martyrdom has been credited with turning popular opinion against the revolutionary regime and its fanatical leader, Maximilien Robespierre, who was overthrown and then guillotined just ten days later.

Three of the order survived. One of them, Mother Marie of the Incarnation, who appears as a major character in Poulenc’s opera, later wrote a History of the Carmelite Nuns of Compiègne, which was published in 1836. Seventy years later, Pope Pius X beatified the martyrs. Pope Francis canonized Mother Marie in 2014, and in February 2022 he decreed that the executed nuns were eligible for the rarely used procedure of equipollent canonization, by which they may be raised to sainthood without the standard proof of miracles. In the 1930s, when Europe was again threatened with virulent totalitarianism, the German aristocrat and writer Baroness Gertrud von Le Fort—born into a Prussian family of Huguenot origin—was moved by Mother Marie’s History to write a novella fictionalizing the nun’s fate. Titled The Last at the Scaffold, its heroine was an invented character based on the author called Blanche de la Force—a thinly disguised version of “Le Fort” with a Christian name meaning “white” and symbolizing purity. This was Bernanos’s major source, and it passed down more or less intact to Poulenc for his La Scala commission, despite a prolonged legal battle over the rights.

Blanche enters the opera as the neurotic daughter of a noble family. She is haunted by premonitions of dark days to come and resolves to enter the Carmelite order. Chafing under its discipline, she has a crisis of faith as the nuns progress toward their ultimate fate. Encounters with the dying prioress of the order, Madame de Croissy, the new prioress Madame Lidoine, and Mother Marie, allow her to work through her feelings in dramatic dialogues that are really appeals to the audience. The fourth wall is never broken, but the economy of Bernanos’s dialogue as adopted by Poulenc for his libretto shines through. Finally, Blanche decides to share the faith of the order and is spiritually reinforced to accept martyrdom in the face of injustice. In our own dark times, it is a fine lesson for those facing the trials of wokeness and its rejection of truth as well as faith and justice.

The lithe soprano Ailyn Pérez sang Blanche with delicate beauty and refined determination. Mezzo-soprano Jamie Barton sang a haughty Mother Marie and proved a more than adequate foil in their dialogues, which show the characters essentially switching roles: the neurotic Blanche achieves serenity in faith, while Mother Marie loses confidence in dogma to become the victim of neurosis as crisis overwhelms the order. Christine Goerke, one of the leading dramatic sopranos of our time, was luxuriously cast as Madame Lidoine. Alice Coote’s Madame de Croissy was riveting in her death scene. Sabine Devielhe sang affectingly as Blanche’s friend Sister Constance. Laurent Naouri was a stentorian presence as Blanche’s father, the Marquis de la Force.

Poulenc’s score relies on words that give rise to the music—not unlike the Wagnerian tradition he initially rejected as a young composer. Also like Wagner, the action is linked by plangent leitmotifs, though the harmonic progressions more readily recall the airy plasticity of Debussy, who disclaimed what he referred to as Wagner’s “calling card” approach but gave homage to it nevertheless. Bertrand de Billy masterfully brought it all together from the conductor’s podium. John Dexter’s production, which unfolds entirely on an illuminated cross, dates back to 1977. As a piece of stagecraft, however, it is timeless and continues to attract a loyal following with each revival. Having withstood the test of time, it should be a lesson to the Met’s management as it seeks a new direction.