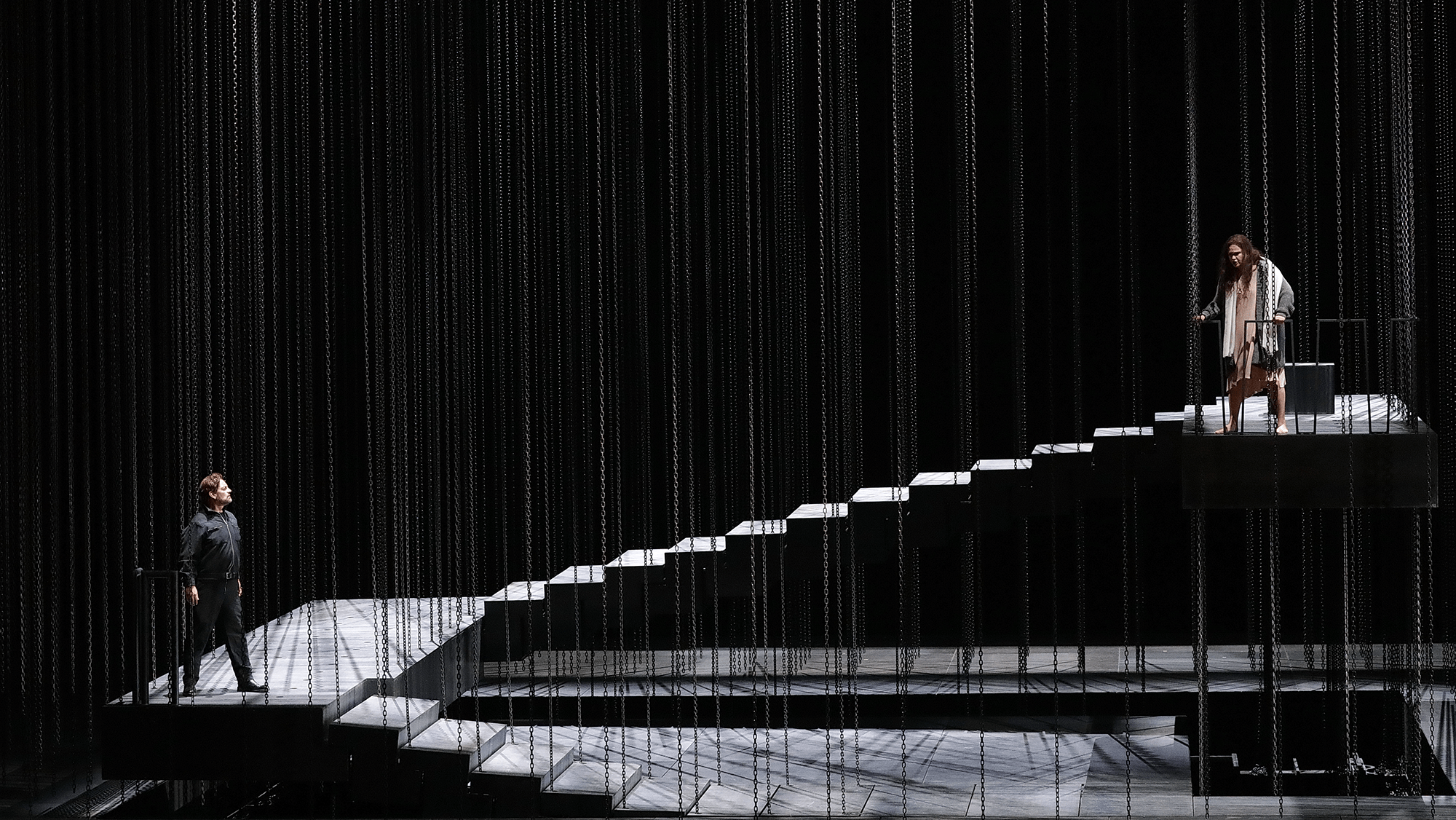

Photo: Teatro Alla Scalla

“Mais c’est tout Parsifal,” said the German composer Richard Strauss when he first heard Claude Debussy’s opera Pelléas et Mélisande at the beginning of the last century. Strauss was imparting his impression that Debussy’s opera, which was meant to escape the musical influence of Parsifal’s composer Richard Wagner, had in the end merely been derivative of Wagner’s final work. A German composer hearing Italo Montemezzi’s L’Amore dei Tre Re (The Love of Three Kings, 1913) might be forgiven for quipping “Ma è tutto Tristan,” given both its densely harmonic score and its plot, which is centered, like that of Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde, around adultery, honor, death, and forgiveness at a royal court in a mythic past.

Pelléas et Mélisande has its fans, and until recently enjoyed a renaissance of performance, but even in Montemezzi’s native Italy his opera—the only lasting contribution of his nine attempts in the genre—has languished on the heap of once successful works that have faded from memory for the sin of being too derivative of Wagner. Milan’s La Scala, however, is finishing up its 2023-2024 opera season by revisiting the work after a 70-year absence.

Wagner found great inspiration in Italy, writing much of Parsifal in Ravello, on the Amalfi Coast, and in Palermo, in Sicily, where the Grand Hotel des Palmes still maintains a ‘Sala Wagner,’ and where devotees of Pierre-Auguste Renoir will recall that the great French impressionist painted Wagner’s final portrait (true to form, Wagner disapproved of the final product, saying it made him look like a pastor or the “embryo of an angel”). Wagner’s works, however, only trickled into Italian theaters slowly, heralded by the next generation of musicians after Giuseppe Verdi, who wrote sprawling scores on subjects from mythology to the Middle Ages. It is rarely remembered that Ruggero Leoncavallo, today known only for his short verismo opera Pagliacci, envisioned a multipart cycle of operas modeled on Wagner’s epic tetralogy The Ring of the Nibelung.

Born in 1875, Montemezzi was certainly part of that movement, creating L’Amore dei Tre Re with a libretto by the playwright Sem Benelli, who adapted his own drama Archibaldo. The inspiration was in the remote past, in a post-Roman Italy only one generation removed from conquest by invading Germanic tribes. Archibaldo, the Germanic king of Altura, is old and blind but remains impassioned, comparing his conquest of 40 years earlier to the seduction of a beautiful woman. Despite losing his sight, he still sees more than his son Manfredo can see, namely that Manfredo’s wife Fiora, a noble daughter of the indigenous Roman society, is having an affair with her fellow native noble Avito, to whom she was engaged before Archibaldo compelled her arranged marriage to Manfredo.

Montemezzi insisted that Archibaldo harbored his own lust for Fiora (after all, the title of the opera requires three men of royal rank instead of the plot’s two nominal rivals), and in part this drives him to try to foil the lovers. But the servants upon whom he relies protect them as best they can until, eventually, Archibaldo overcomes their deceit and decides he has enough on Fiora to strangle her to death. When Fiora’s body is laid out for mourning, Archibaldo contrives yet more revenge, smearing poison on her dead lips in the expectation that Avito will give her corpse one final, fatal kiss. The old king’s instincts are correct. Avito promptly arrives to kiss his dead mistress and quickly dies, confessing his sin to Manfredo, who forgives the adulterous couple and then himself kisses Fiora’s poisoned lips. As Manfredo expires in turn, Archibaldo is left to mourn in despair, an unwitting victim of his own twisted revenge.

The dramatic similarities to Tristan immediately stand out. The honor of an old king in an ancient realm is befouled by the adulterous affair of a younger couple who nevertheless know true love, which both predates and eludes the legitimate marriage in question and thus draws understanding. Passions among the characters are otherworldly in their intensity. Ultimately, only death can resolve the dilemma and, as in Tristan, the resolution follows a magnanimous act of belated forgiveness proffered by the injured party at a fatal moment.

Musically, the similarities are even greater. Although Montemezzi neither completely discarded his native tradition’s lyricism nor escaped the subtle orchestral colorations found in Debussy, he wrote a score that incorporated Wagner’s unending melody, discarded traditional arias in favor of monologues and dialogues, used repeated motivic elements to suggest characters and emotions, and indulged in richly scored scenes to convey a dreamlike sensibility permeating the consciousness of his characters.

As in Tristan, the dramatic center rests in the middle of the second act, in an interrupted love scene in which the adulterous tenor-soprano couple—here Avito and Fiora—explore the true depths of their feelings, only to suffer the intrusion of phenomenal reality when the offended old bass-voice king—Archibaldo rather than Marke—finds them out. Montemezzi favored the Tristan scene so much that he scored two duets for Avito and Fiora, along with a separate duet for Manfredo vainly to beseech Fiora to return his affection.

These similarities do not at all disqualify L’Amore dei Tre Re as a great opera. The music is ravishing from start to finish. The characters are complex and compelling. The story can be understood on its own merits by an audience unfamiliar with Wagner’s operas and uninformed by the profound philosophical and psychological dimensions of Tristan, which was itself such a powerful legend that it found retellings across half of Europe—and perhaps farther afield—long before it was written down and centuries before Wagner got to it. These merits reasonably outweigh L’Amore dei Tre Re’s contrivances, which are admittedly considerable: a strangulation by an old blind man, a dead woman’s poisoned lips that kill not one but two males leads, too many love duets, and a buildup that arguably goes on too long, taking almost an hour and a half to peak before resolving in a final act of just over twenty minutes.

But Montemezzi’s opera can pass what is perhaps the most important test of all for operas that hold the stage: it can thrive outside of its traditional setting. L’Amore dei Tre Re’s 1913 premiere offered a lavish set that could easily have substituted for a compellingly traditional production of Tristan, Pelléas, or any other opera involving ancient kings, passionate courtiers, and transcendent romance. La Scala’s new production, by Àlex Ollé of the Catalonian La Fura dels Baus collective, dispenses with all the fripperies. Altura is an oppressively modern place, defined by a metallic ramp that changes configuration to allow the characters to move toward, against, and away from each other. Oppressive chains hang from the ceiling to form barriers that are foreboding but easily permeable. Lluc Castells’s costumes—mainly black tunics—suggest the sort of modern authoritarianism which would be capable of crushing romance with chokings and poison. The only lightness comes in an arrangement of lilies for Fiora’s death litter, an allusion to her people’s comparison of her to that flower.

L’Amore dei Tre Re’s premiere 110 years ago was a mixed success, but with the fervid support of the conductor Arturo Toscanini it quickly triumphed, taking the stage of New York’s Metropolitan Opera only a few months later, in January 1914. It remained in regular repertoire there for about four decades, with the famous tenor Enrico Caruso eventually singing the role of Avito. In 1949, the soon-to-be-defunct Opera News dedicated an entire issue to Montemezzi’s opera.

The composer became internationally famous and married an American heiress whose generosity may have sapped his creative energy. In any case, he had almost no other successes before his death in 1952. His one hit lasted until the explosive revival of the long-neglected bel canto school supplanted heavy Romanticism as the Italian repertoire’s preferred operatic idiom. A number of recordings have since been made, but stage productions are exceedingly rare. No other opera company in the world appears to have it programmed in the near future.

La Scala’s look back at this forgotten classic was as grand as one could hope. As Archibaldo, the stentorian Russian bass Evgeny Stavinsky cut a commanding figure, though he both looked and sounded rather too young for the part, which needs to draw on the many hurts and disappointments realized by one’s mature years. The exceptional tenor Giorgio Berrugi is rapidly building an international career in high dramatic tenor parts, and his Avito was another clarion triumph. Chiara Isotton sang prettily—and pretty deceptively—as Fiora, whom the great Scottish-American soprano Mary Garden described a century ago as “a superb liar and the most complicated character in the operatic repertoire.” Isotton mastered ace delivery of resolute but vulnerable lines. In bluff baritonal tones, Roman Burdenko’s authoritative Manfredo captured the part’s defensive pride and nobility in suffering. Approaching 80, veteran conductor Pinchas Steinberg allowed the score to bloom in its highly chromatic moments, which were many.