When all economists agree on something, it is time to leave the room and get some fresh air. The Greeks know all too well what happens when economists rally around a set of data that they cannot explain.

Something similar is in the making among Europe’s central bankers. It doesn’t have to be very dramatic, but just like with economists who recommend disastrous fiscal policy measures—as in Greece a decade ago—central bankers can do a lot of harm by suddenly running off in the same policy direction.

There is an odd consensus among Europe’s central bankers about what inflation is going to look like next year. As I will explain in a minute, this consensus makes no sense, which makes me wonder what is really behind it.

Generally speaking, there is nothing strange with central banks mimicking each others’ policy decisions. The Federal Reserve has been guiding the European Central Bank through the increases in interest rates over the past 18 months. This has benefitted the monetary-policy fight against inflation: it has vacuumed the American and European economies of excess liquidity and brought inflation down significantly.

On December 14th, the European Central Bank “decided to keep the three key ECB interest rates unchanged.” Its decision followed a day after the Federal Reserve decided to do the same.

Officially, the ECB motivates its decision as follows:

While inflation has dropped in recent months, it is likely to pick up again temporarily in the near term. According to the latest Eurosystem staff projections for the euro area, inflation is expected to decline gradually over the course of next year

Let us note that little comment about inflation “likely to pick up again temporarily.” It will become significant in a moment.

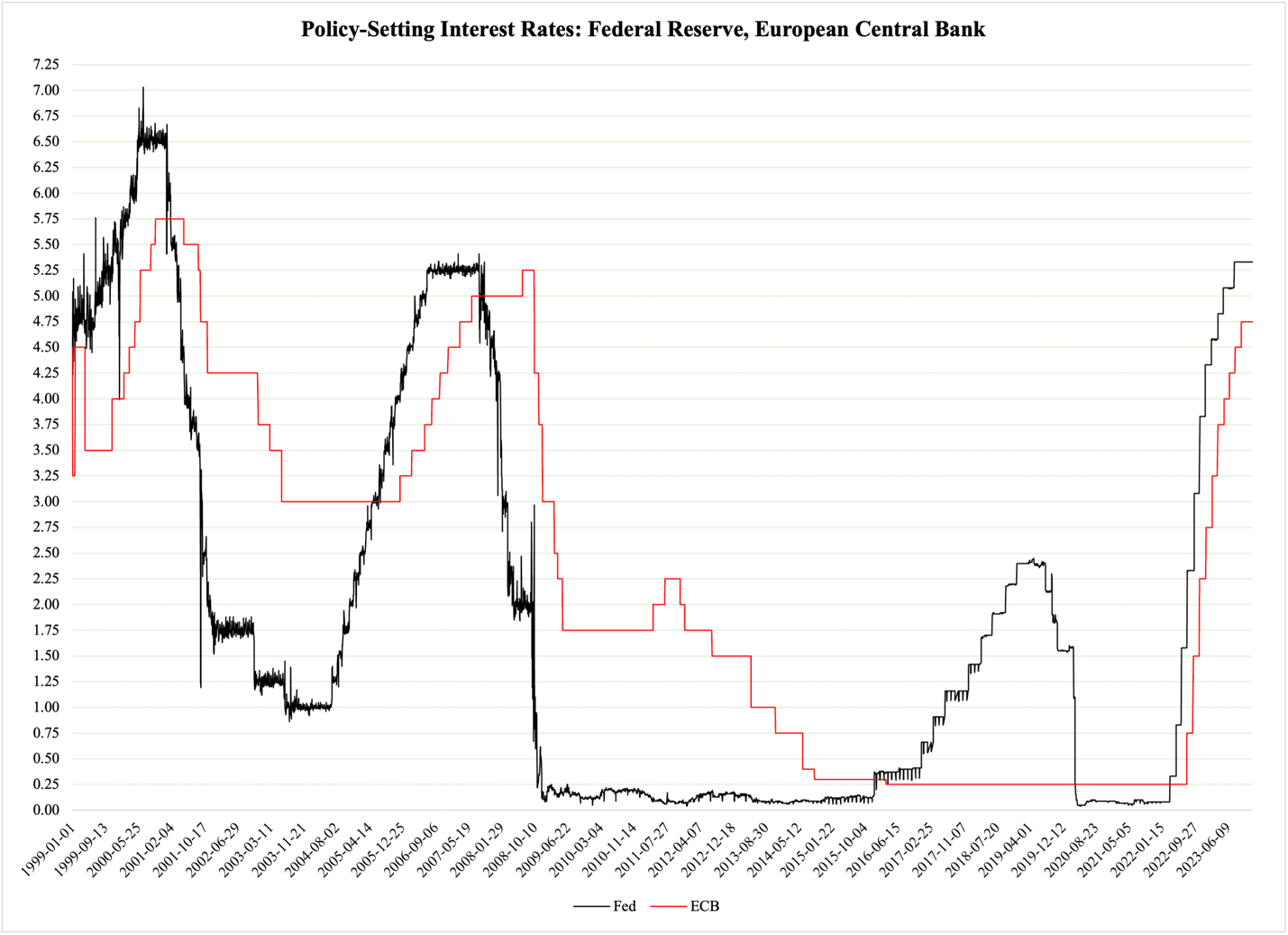

While the ECB’s official motivation for unchanged interest rates has to do with inflation, its real reason is the Federal Reserve’s decision a day earlier. As Figure 1 reports, comparing the Fed’s funds rate and the ECB’s marginal lending facility, the ECB has been following carefully and closely right behind the Fed:

Figure 1

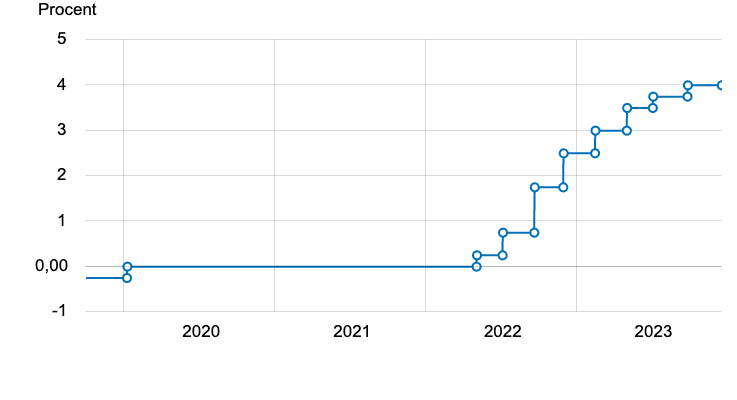

The ECB was not the only central bank that echoed the Fed’s latest decision. In Sweden, where the Riksbank has raised its governing interest rate repeatedly in the past 18 months, the central bank has kept the rate unchanged at 4% since November 29th:

Figure 2

The Swiss National Bank also left its policy rate unchanged. In its monetary policy assessment of December 14th, the SNB explains:

Inflationary pressure has decreased slightly over the past quarter. However, uncertainty remains high. The SNB will therefore continue to monitor the development of inflation closely, and will adjust its monetary policy if necessary to ensure inflation remains within the range consistent with price stability over the medium term.

With an inflation rate of 1.4% and one of the strongest currencies in the world, the Swiss central bank can keep its policy rate at 1.75%. However, the big point here is the SNB’s warning that “inflation is likely to increase again somewhat in the coming months.” The ECB said almost exactly the same thing in its monetary policy statement:

While inflation has dropped in recent months, it is likely to pick up again temporarily in the near term.

Over in London, the Monetary Policy Committee, MPC, of the Bank of England also met on December 14th. They decided to keep the policy-making bank rate unchanged at 5.25%.

As for inflation, the MPC explains:

CPI inflation is expected to remain near to its current rate around the turn of the year. In particular, services price inflation is projected to increase temporarily in January … before starting to fall back gradually thereafter.

The same odd prediction of a temporary bump in inflation, but with different causes to explain it. While the Swiss central bank blames the predicted inflation bump on a rise in the value-added tax, the Bank of England blames “base effects from unusually weak price movements” in early 2023.

In other words, a technicality.

This kind of similarity in forecasts across different clusters of economists is always curious. It means that their forecasting models likely share significant components, and that they rely to a large degree on the same theoretical framework as they interpret their data. That, of course, defeats the purpose of having different forecasting outfits in the first place, but when they attribute the same predictions of an uptick in inflation to different causes, we have good reasons to question their forecasting prowess.

The likely reason for this oddity is that they, as mentioned, fundamentally use the same forecasting model but that they lack the full theoretical acumen to explain their forecasts.

Put simply: when an economic model says that inflation is going to rise temporarily at a specific point in the near future—in this case in early 2024—and there is no apparent theoretical explanation of that rise, then the first reaction from the economist should be to question the rise itself. You then step away from the model, look at the economy without your econometric glasses on, and ask yourself if the quantitative prediction of higher inflation ‘makes any sense.’

In defiance of the collective wisdom of the economists at the ECB, the Swiss National Bank, and the Bank of England, I will audaciously claim that there is no specific reason for inflation to tick up in early 2024. That does not mean a ‘bump’ could not happen—it certainly could. We know from the stagflation era 40 years ago that as inflation is coming down from a high peak, the ride is a bit bouncy.

However, the fact that several central banks predict the same bump but give it different causes, suggests to me that there is something else afoot here. It could be as simple as an agreement among central bankers to find a way to quell the debate about lower interest rates. Talk about a possible uptick in inflation would give the central banks enough leeway to return us to lower interest rates on their own terms.