On December 19th, Eurostat released the good news that

euro area inflation rate was 2.4% in November 2023, down from 2.9% in October. A year earlier, the rate was 10.1%. European Union annual inflation was 3.1% in November 2023 … A year earlier, the rate was 11.1%.

This is good news for Europe going into 2024. The euro zone is now close to the European Central Bank’s long-term inflation target of 2%.

There is also a bit of irony in this: The inflation that the ECB can now claim to have defeated resulted from their very own money printing in 2020 and 2021.

Returning from the garden of low-hanging rhetorical fruit to the positive news on the inflation numbers, there is now a good chance that the ECB will start cutting interest rates early in 2024. I would caution against excessive optimism on this issue. For the good of its own self-image, the central bank is going to try to be at least a little bit monetarily conservative.

At the same time, there is already a good reason for them to cut rates early in the new year: the latest numbers for economic growth. Here are the five latest real, annual growth rates for the euro-zone GDP:

The euro zone has lost two full percentage points’ worth of annual economic growth. This may not sound like much, but it is the difference between an economy doing relatively well and an economy heading straight into a recession.

To be clear, the loss of growth is not evenly spread. With the exception of Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, and Romania, the euro zone countries are either below 1.6% GDP growth, or already have shrinking economies (that would be 9 of the 20 euro-zone members). Portugal is quickly diving toward negative GDP.

In short: expect more bad news across the currency area when the fourth-quarter numbers are out.

The EU as a whole is doing equally poorly, with negative GDP growth in 13 out of 27 member states.

If the euro zone’s GDP shrinks in the fourth quarter as well, it will meet the statistical definition of a recession. One reason to believe that this will happen is in the inflation numbers for October and especially November.

If GDP for the third quarter had been at least to some degree as strong as the remarkably resilient U.S. economy, then lower inflation would have been a sign of structural strength and successful monetary conservatism. As things are now, though, the move down toward 2% inflation becomes a bearer—or booster—of bad news: recession.

I am a bit worried by the very pace of the emerging recession. A proper evaluation requires the full fourth quarter of data for GDP, the labor market, and inflation, and my mainline prediction for 2024 is a regular recession for the euro zone. However, until otherwise convinced by new information, I am not going to rule out that the euro zone is in for a serious recession.

The December inflation figure will be a very important indicator, especially in how far it falls relative to November. It is essential, though, to keep in mind that when reviewing inflation in the context of forecasting, the figures do not always convey the same information. There are different types of inflation which replace each other over time as the dominant cause of price increases.

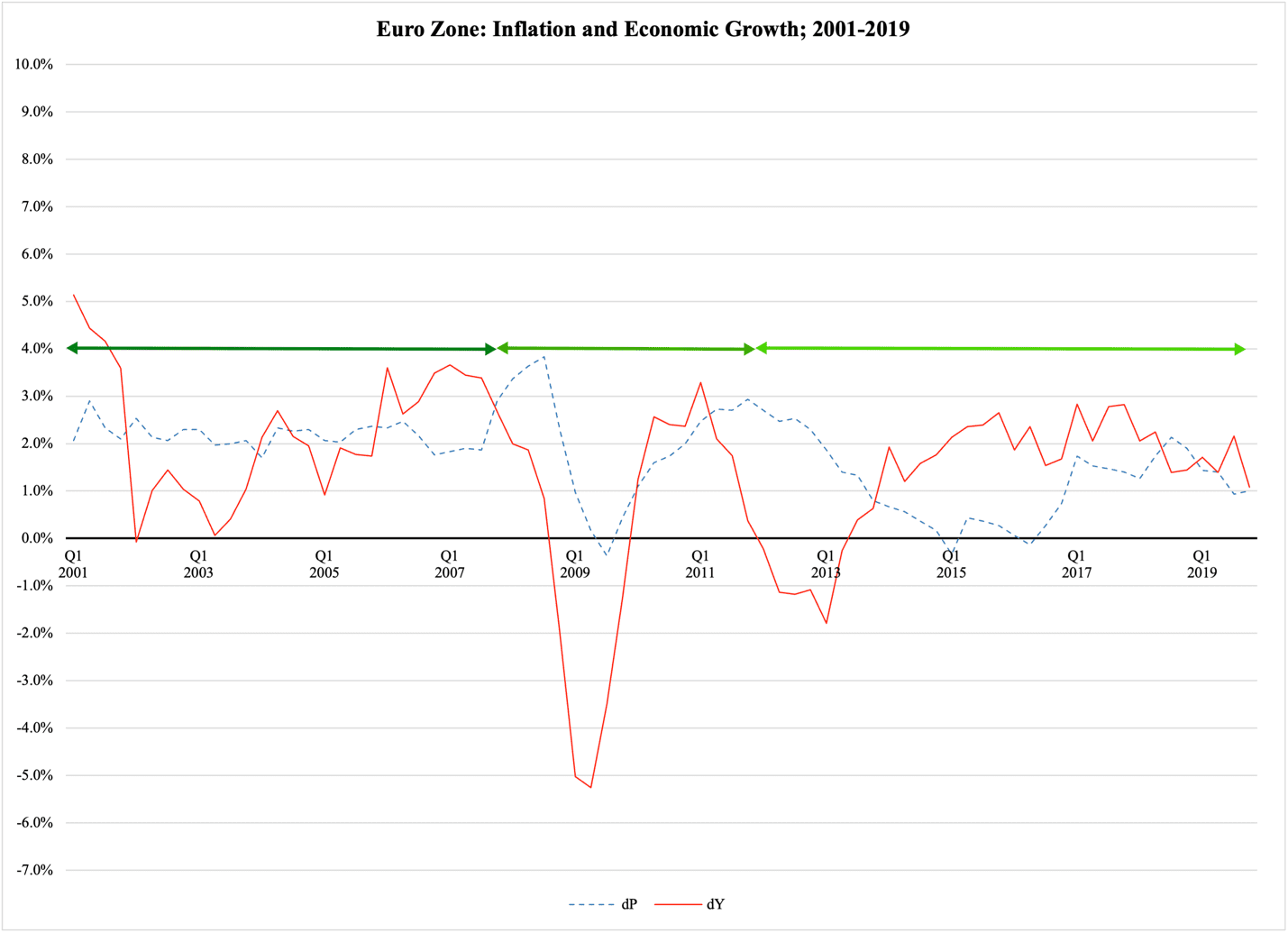

Figure 1, comparing real GDP growth and inflation rates for the euro zone in 2001-2019, gives a long enough time frame for a good overview of what this means. The first, dark green arrow, covering 2001-2008, represents a period of monetary conservatism. Economic growth (red solid line) picked up well from the Millennium recession and even reached a respectable 3% in the later part of the period. Inflation (blue dashed line) was remarkably stable at around 2%, in itself an indicator of sound monetary policy:

Figure 1

The type of inflation visible in the first period in Figure 1 is the simple demand-pull type that signifies a healthy, expanding economy. It is perfectly consistent with the gradual increase in GDP growth and, again, the monetary conservatism of a young European Central Bank.

The second, middle green arrow represents the first episode of monetary accommodation on behalf of the ECB. This is the so-called Great Recession, when the euro zone’s central bank for the first time abandoned its conservative policy and began buying government debt. In other words, this is where the ECB laid the groundwork for a shift in the type of inflation that we would see in the euro zone.

Speaking of inflation: after a dip to zero at the bottom of the recession, it briefly returned to what looked like more normal values. However, something important happens in the third episode—the period marked by the light green arrow—that tells us that we are no longer looking at the kind of demand-pull inflation from the first episode:

These two things cannot happen at the same time—unless we are looking at a new type of inflation. That new type is driven not by economic activity, but by the growth in the money supply.

Monetary inflation is the most dangerous of all types of inflation, especially when the printed money is being used in support of fiscally unsustainable governments. When excessive amounts of money enter a normal, well-working economy like the euro zone, the first thing that happens is that resources are called forward, ‘brought to the market’ so to speak, that otherwise were held in storage for contingency purposes. Industrially speaking, this means that the entire economy gradually reduces its margins of error, trying to sell more today and worrying less about the morrow.

This de facto supply-side effect depresses market prices but does so on the artificial grounds of a fast-growing money supply. As the monetary expansion continues, the reserve resources are depleted; there are now large amounts of money sloshing around in the economy creating demand without creating supply.

In the case of the euro zone, this happened because the ECB kept supporting fiscally unsustainable governments. Monetary inflation slowly grew in significance all the way through 2019.

Then came 2020, which we will review as we take a look at what 2024 may bring. Stay tuned.