As Europe slowly emerges from the painful inflation experience of the last year-and-a-half, a new threat is rising over its economy: a recession. I pointed this out two weeks ago, but I did not elaborate on the full scale of the risks that come with a recession. Since then, Eurostat has released new data on inflation, which gives us a better idea of exactly where the European economy is heading.

A shift has taken place in one of the most important macroeconomic relations, namely that between inflation and unemployment. The stable relationship between these two variables, known in economics parlance as the Phillips curve, is being replaced with a relationship that is consistent with stagflation.

In other words, the risk of stagflation in Europe has increased. It is not a dramatic uptick in the risk, and I am not predicting that stagflation is imminent. However, the change—which is consistent with economic theory and therefore analytically explainable—is enough to put policymakers on alert across the European Union.

Before we look at the data that reveals this heightened risk, let us remember what stagflation is. Combining high unemployment with high inflation, stagflation is one of the most destructive forces that can hit an economy. Workers who are laid off are hit with a double whammy: lost income and a rapidly rising cost of living. If allowed to become entrenched, stagflation can have major social and political consequences.

Fortunately, episodes of stagflation are not very common. Since the global episode in the late 1970s and early 1980s, there have only been isolated incidents around the world. They have usually been driven by extreme inflation rates of hundreds, thousands, or—as in Venezuela—millions of percent. This is probably one reason why so few economists examine the European economy today in search of stagflation signs.

Again, I am not making a dramatic prediction of imminent stagflation. Such drama would be without merit. However, if only small changes happen in the landscape of economic policymaking, the stagflation outlook could change dramatically—and quickly.

I pointed to the stagflation risk back in February, in particular in the context of monetary policy. In response to the fears of persistently high inflation and unemployment, I explained that “central bankers are well advised to tighten the money supply now, while they can still control inflation.” While acknowledging the painful impact of higher interest rates, I added that higher rates would be preferable to stagflation, not as a better alternative, but as a less painful one.

So far, the European Central Bank has followed this path, raising its interest rates on several occasions recently. Since last summer, e.g., its deposit facility has increased from zero to 3%. As a result, the trend of rising inflation that we saw last year has been broken: as of March this year, according to Eurostat’s latest numbers, inflation in the euro zone was 6.9%, down from a peak of 10.6% in October. Inflation is higher in the EU as a whole than in the euro zone, though 8.3% in March is a significant improvement over the top rate of 11.5% in October.

There is more good news: three of the four countries that have had inflation rates in excess of 20% are now below that ominous threshold:

The bracket of 20-50% inflation is often considered the first step toward hyperinflation. There does not seem to be any risk of that, at least not now. The only remaining country above 20% is Hungary, and its inflation rate has stabilized recently. The Hungarian inflation rate stood at 7.5-8% in early 2022, then accelerated steadily until it peaked at 26.2% in January. The figure for March, 25.6%, is still high, but—again—the rise has been replaced with inflation ‘stalemate.’ There are good reasons to believe that Hungarian inflation will slowly subside from here on; families and businesses should look forward to a slow return to less problematic inflation rates in the coming months.

Despite the good news about a slow inflation reversal, there is still a worrisome message buried in Eurostat’s inflation numbers. To date, 11 EU member states remain above 10%, and not a single member state has come back to the 2-2.5% rates that we got used to prior to 2020. The lowest rates are in Luxembourg and Spain at 2.9% and 3.1%, respectively.

If all that happened in the European economy was the slow decline in inflation, there would be little reason to worry about stagflation. Unfortunately, unemployment is rising, which is inconsistent with the macroeconomic theorem known as the Phillips curve: normally, inflation and unemployment vary in opposite directions; as inflation is coming down, it is only natural to expect unemployment to rise.

The problem is that inflation is not coming down fast enough. Only four EU member states have inflation rates below 4%, and the trend downward is too weak to inspire confidence, especially outside the euro zone. There is an elevated risk that inflation does not return to ‘normal’ rates before unemployment becomes a major problem.

As of February, euro zone unemployment stood at 6.8%. This is a tick down from February’s 6.9%, but noticeably higher than the 6.4% post-pandemic low point in June last year. Greece and Spain have the highest unemployment rates: 11.5% and 13.3%, respectively. While the Greek number is virtually the same as it has been since last summer, Spanish unemployment has gone up from 12.2% back in June.

The trend of rising unemployment is not consistent:

With that said, the overall trend is that jobless rates are ticking up, and when coupled with the most recent inflation numbers, a picture emerges: in 2022, Europe moved closer to stagflation.

Prior to 2022, the European economy—writ large—behaved pretty much as the traditional Phillips curve suggests, which means it did not behave at all in a way that would indicate stagflation. The Phillips curve, or Phillips theorem, says that inflation is high when the economy is strong, GDP growth is high, and unemployment is low. By contrast, when the economy is in a recession with high unemployment, inflation declines to low rates.

This inverse relationship between inflation and unemployment relies on one specific assumption, namely that inflation is the result of high economic activity. With strong demand for goods, services, capital, and labor, prices go up throughout the economy. The inflation that we are currently experiencing is not of this demand-pull type: it is entirely a monetary phenomenon, i.e., created by excessive money printing in 2020 and 2021.

While demand-pull inflation rises and falls with the opposite movements in unemployment, monetary inflation is independent in that regard. We can see some traces of this independence in recent statistics on inflation and unemployment in Europe. For comparison, we first examine how the two variables changed prior to the big money-printing frenzy of 2020 and 2021.

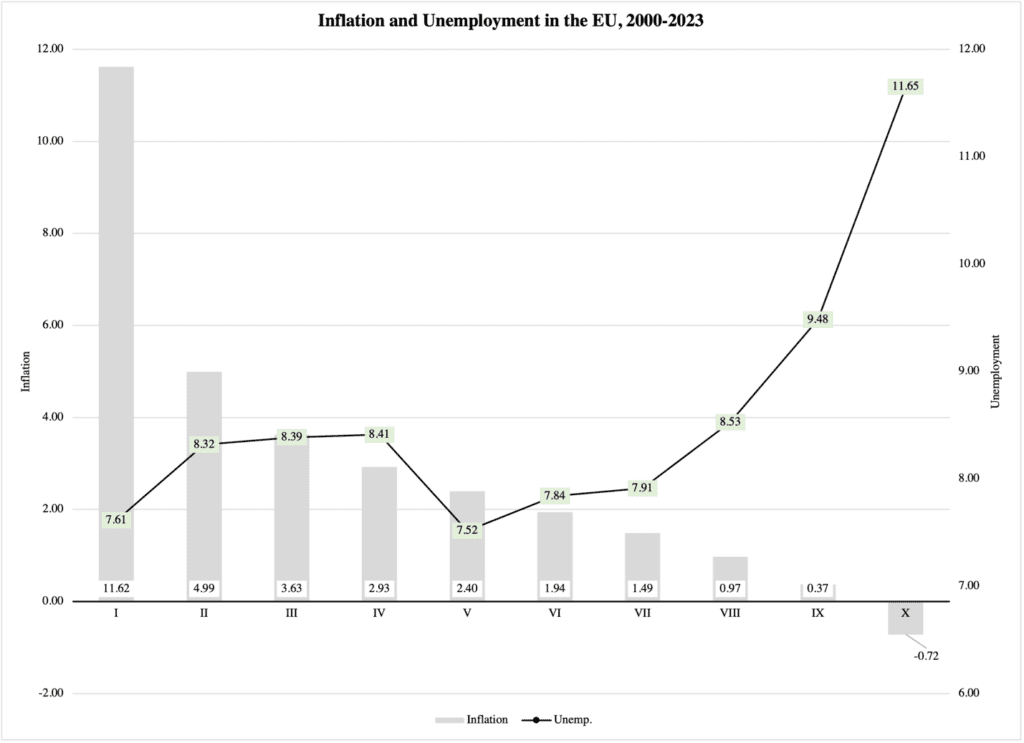

Figure 1 reports observations of inflation and unemployment in the 27 member states. The data is presented monthly from January 2000 through February 2023; the total number of data pairs—inflation paired with unemployment per month per EU member state—is then divided into ten different groups, based on how high inflation is. The data pairs with high inflation are clustered in Group I, where the average inflation rate is 11.62%; for those data pairs, the average unemployment rate is 7.61%.

The data pairs with the lowest inflation rates have an average inflation rate of -0.72%, in other words, deflation. For those data pairs, the average unemployment rate is 11.65%:

Figure 1

Source of raw data: Eurostat. Total number of data pairs: 7,506. Eurostat does not report inflation or unemployment for all the years observed for all its current member states.

Figure 1 reports a relatively good Phillips curve. This means that overall, for the past 23 years, Europe has been experiencing demand-pull inflation, and the economies of the member states have by and large worked as standard macroeconomic theory suggests. This has made life predictable, with moderate inflation and balanced (though often sluggishly growing) economic activity.

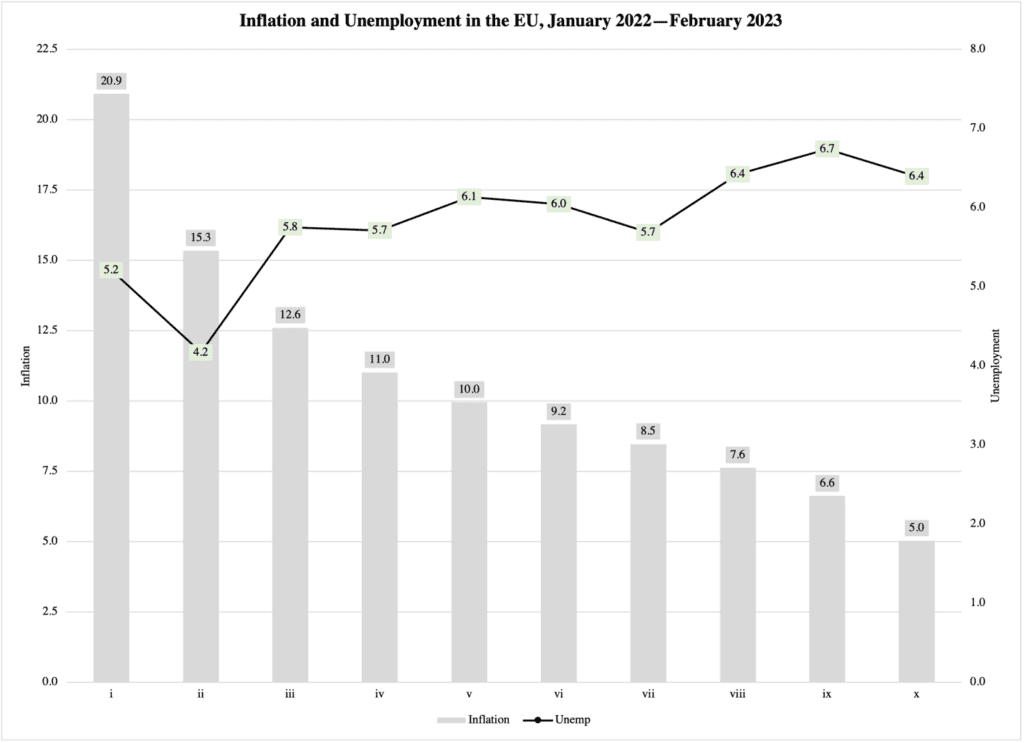

The nature of Europe’s inflation changed with the monetary expansion that took place during the pandemic. Figure 2 reports the same data as in Figure 1, but only for the period from January 2022 through February 2023. The number of data pairs is a lot smaller, of course, but there is nevertheless a visibly different relationship between unemployment and inflation. While the inflation rate varies from an average of 20.9% in the first decile to 5% in the tenth, there is very little change in unemployment.

Figure 2

Source of raw data: Eurostat. Total number of data pairs: 406.

If we accept the message in Figure 2—and we have good reasons to do so—we should also be concerned about the risk of stagflation. While inflation, as mentioned, is slowly trending downward across Europe, it would not take much to reignite the fire. Two weeks ago I predicted that the European Central Bank would soon abandon its monetary tightening and start printing money again.

I made this prediction for one simple but serious reason: the trend of rising unemployment, while not unionwide yet, is a harbinger of a recession. When it happens, people lose their jobs and their incomes, businesses cut down on investments, and fewer entrepreneurs want to start a new business. Overall economic activity plummets and tax revenue declines with it. At the same time, demand for public assistance increases, both from the unemployed and from still-employed workers who make less money.

The result is a budget deficit, to which member state governments can respond with either austerity to close the deficit or more government spending to stimulate growth. The former policy can have downright catastrophic consequences, but that does not mean the latter is a preferable strategy. A monetary expansion to finance government deficits, namely, fuels more inflation.

Despite the consequences of the ECB monetizing budget deficits, i.e., printing money to buy government debt on an ongoing basis, I am convinced that when deficit-ridden member states start contemplating Greek-style austerity policies, the ECB will come to the ‘rescue’ with newly printed cash. It will not be an independent choice by the central bank, but a de facto request from the EU: austerity policies bring out the worst of a country’s democracy, causing social upheaval and giving rise to political extremism. Of the two options, austerity or monetary expansion, the ECB will choose the latter.

The obvious risk with this policy choice is that inflation takes off again. The so-called transmission mechanisms, in other words, the economic channels of cause and effect, are already in place, ripe and ready to funnel more newly printed cash into inflation. If that happens, Europe will be trapped in stagflation for a long time.

Hopefully, decision-makers at the EU level will see the tremendous risks that come with using the ECB’s money supply as a line of credit for member states with grave deficit problems. But what should they do instead of austerity or money printing? That is what next week’s Fiscal Forecast will talk about!