Italy’s Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni is pictured at the Italian Senate on the eve of an European Council, in Rome on October 22, 2025.

Alberto PIZZOLI / AFP

There is a lot of unwarranted controversy around Europe’s conservative governments, with Hungary’s Prime Minister Viktor Orbán as the best-known example. For reasons that I will not delve into here, right-of-center leaders are unfairly targeted and even attacked with outright lies.

Alongside Orbán, Italian Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni has drawn loads of negative attention. While most of the critical attention lacks merit, there is one point where Meloni’s opponents do have a point. In a recent editorial, the French newspaper Libération targets Italy’s economy under Meloni’s government:

Giorgia Meloni, or the Italian economic miracle… This refrain has been playing out for the past few months. … It’s true, we’ve never tried it. But to rely on Giorgia Meloni’s economic results to suggest that, on top of everything else, it’s working, not even working poorly, that everything is fine, is a lie. Because there is no Italian economic miracle.

The Libération provides no evidence to back up their claim. However, all relevant macroeconomic data suggests that they are correct: so far in her tenure as prime minister, Meloni has made no difference for the better.

To be clear, her government has not made the economy worse either, which strictly speaking neuters the point by the French newspaper. France would be neither better nor worse off if its government had copied Meloni’s fiscal policy over the past three years.

The problem for Meloni is that the 2027 election is less than two years away, and it takes time for economic policy to make a difference in people’s lives. Fiscal policy, which includes taxes and government spending, usually needs 1-1.5 years to make a difference. Therefore, if the Meloni government wants voters to see her policies improve their finances, she would be well advised to roll up her sleeves and get to work.

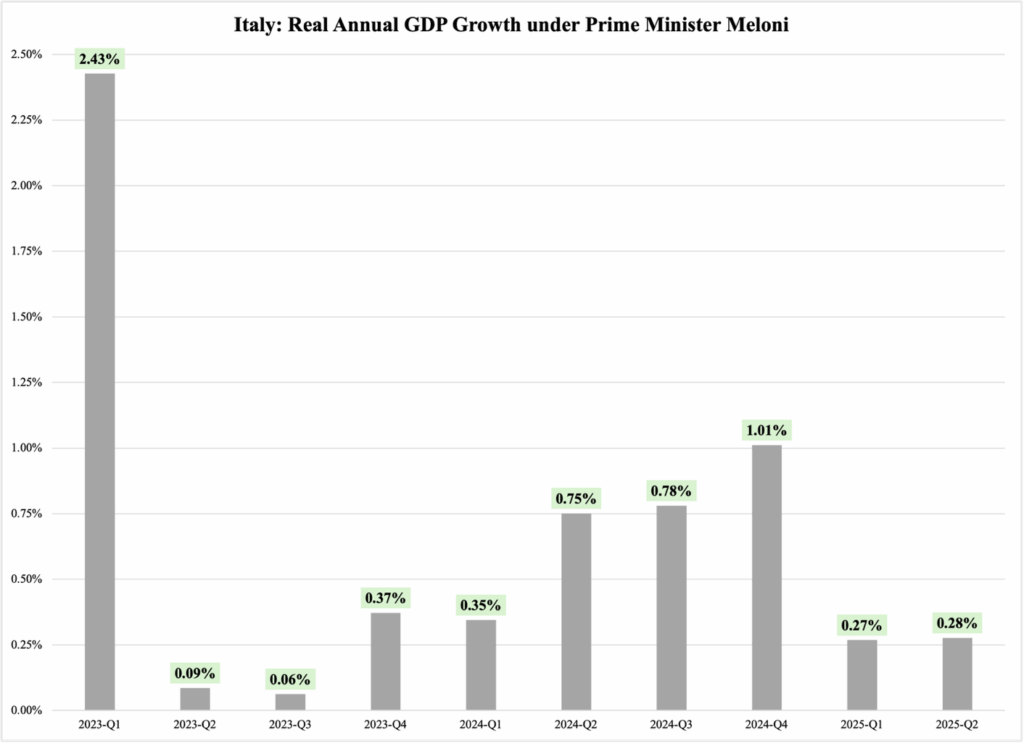

To start with the most common and most basic macroeconomic variable, GDP growth, Figure 1 has the record so far for the Meloni government:

Figure 1

There is no other way to slice this cake: the Italian economy under Meloni has not done well. However, contrary to what may be tempting to her political detractors—the French paper Libération included—it is not the case that Prime Minister Meloni has made a difference for the worse either:

This difference is so small that it falls within the fiscal policy margin of error. The only reasonable conclusion is that Giorgia Meloni’s government has made no difference at all, for the worse or for the better, for the Italian economy. For reasons that may be perfectly reasonable and only she can explain, her coalition government has been focused on other policy areas than the economy.

With that said, there is plenty of room for improvements to be made. During the period of time covered in Figure 1, spending by Italy’s consumers increased by 0.3% annually, with not a single quarter in 2024 or—so far—in 2025 above 1.2%. In fact, the trend is toward total stagnation in household spending.

Business investments have done better, but the average of a 4.1% increase per year since 2023 hinges critically on 2023, when investments grew by

Since then, the average has been well below 1% per year.

Exports have been at a standstill with 0.1% per year since 2023, but that has technically improved GDP since imports have actually declined marginally. This makes net exports positive, which adds to GDP, though in this case almost immeasurably.

The only distinctly positive economic numbers for the Meloni government are from the labor market. Total unemployment was 7.7% in 2023, then fell to 6.5% in 2024 and has averaged 6.3% so far in 2025. Among young workers, aged 24 or younger, the numbers for the respective years are 22.7%, 20.3%, and 19.9%.

With a slow downtick in jobless numbers, Meloni’s government presides over the same trend as her predecessor’s administration did. Italian unemployment has been trending downward steadily since 2015, when more than four out of every ten young workers were unemployed; their jobless rate briefly topped 45%.

An often-used figure in public debates over a country’s economic performance is its government’s debt as a share of GDP. In this category, Italy has been at a disadvantage compared to most of its EU peers, and the Meloni government is no exception. Since she took office, the debt-to-GDP ratio has hovered in the neighborhood of 134.5% of GDP. This number compares well to the last few years before the 2020 pandemic.

On the deficit side, the numbers convey a mixed message. A budget deficit of 7.2% of GDP in 2023 fell by more than half to 3.4% in 2024. This is a strong improvement, but the number is still below the 2.2%-of-GDP deficit from 2018 and the 1.5% for 2019.

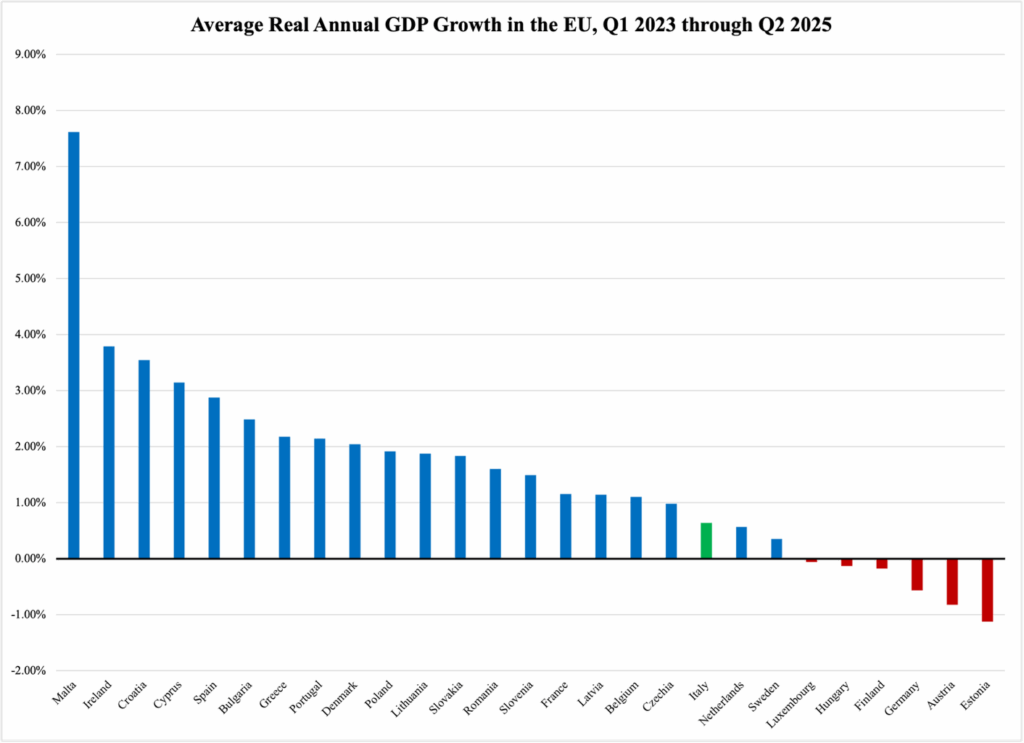

All in all, to date Meloni has left no discernible fingerprints on the Italian economy. There is no doubt that she has her work cut out for her. While none of Italy’s current economic woes are her government’s fault, it is an undeniable fact that her country is in dire need of a substantial improvement on that front. As Figure 2 explains, in terms of GDP growth, Italy (green column) is among the slackers in the European Union:

Figure 2

As a general observation, it is depressing to note that since Europe emerged from the pandemic and its aftermath, only four countries have been able to average 3% or more in real annual economic growth. It is even more depressing to find nine countries below 1% per year. As a rule of thumb, it takes at least 2% real GDP growth per year for a country to sustain its standard of living over time; real progress in prosperity comes only when the growth rate remains above 3% per year.