On August 1, Eurostat released its flash estimate of euro zone inflation for the month of July. Their main point is that inflation seems to be standing still:

Euro area annual inflation is expected to be 2.0% in July 2025, stable compared to June according to a flash estimate from Eurostat

The estimate is based exclusively on July inflation figures from all the 20 euro zone members, which is why Eurostat can firmly report an inflation figure for the currency area but not for the EU as a whole.

Inflation in the euro zone has gently declined from 2.3% in February to 1.9% in May and has remained flat at 2% in the two latest months. This reinforces the impression that there is no real inflation problem in Europe anymore. The same impression is embedded in the components of aggregate inflation:

These outliers are not very far from the aggregate figure, and neither has shown any noticeable volatility over the past few months. Therefore, it is easy to draw the conclusion that the ECB, with its relatively thoughtful monetary policy, has gotten inflation back under control. After all, the central bank’s long-term goal is to keep euro zone inflation at 2%—which is where it has been now for three months in a row.

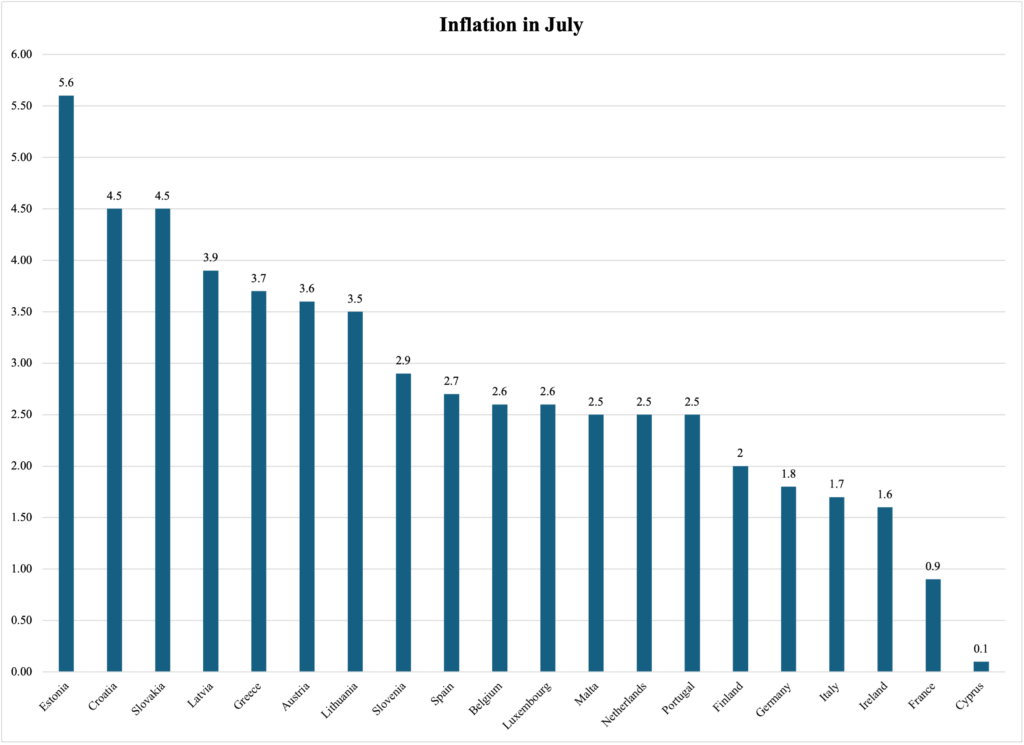

A closer look at the numbers for individual member states gives a different picture. Here are the year-to-year inflation numbers for July:

Figure 1

As Figure 1 reports, seven euro-zone states have an inflation rate above 3%, and another seven recorded a rate in the 2-3% range. The reason why the average for the currency area as a whole landed at a flat 2% is simple: the three largest economies in the euro zone—Germany, France, and Italy—all had inflation rates below 2%. Since they weigh heavily in the index that calculates inflation for the euro zone as a whole, they unintentionally ‘conceal’ the fact that most euro zone members are still struggling with inflation well above the ECB’s long-term goal.

This diversity of inflation rates presents a problem for the ECB. On the one hand, if it loosens monetary policy because inflation on average is back to 2%, then it risks making matters worse in high-inflation countries, primarily Estonia, Croatia, and Slovakia, where inflation currently is above 4%. On the other hand, further tightening of monetary policy to bring down inflation in the 14 member states where it is above the long-term target could send the three big economies into a deep recession.

Based on these figures, it is understandable that the ECB decided two weeks ago to keep its policy-setting interest rates unchanged for now. However, that may not be possible going forward: not only is the euro zone home to very different inflation rates, but there is an underlying trend of inflation rates becoming polarized.

In short, when it comes to inflation, the euro zone seems to be splitting into two.

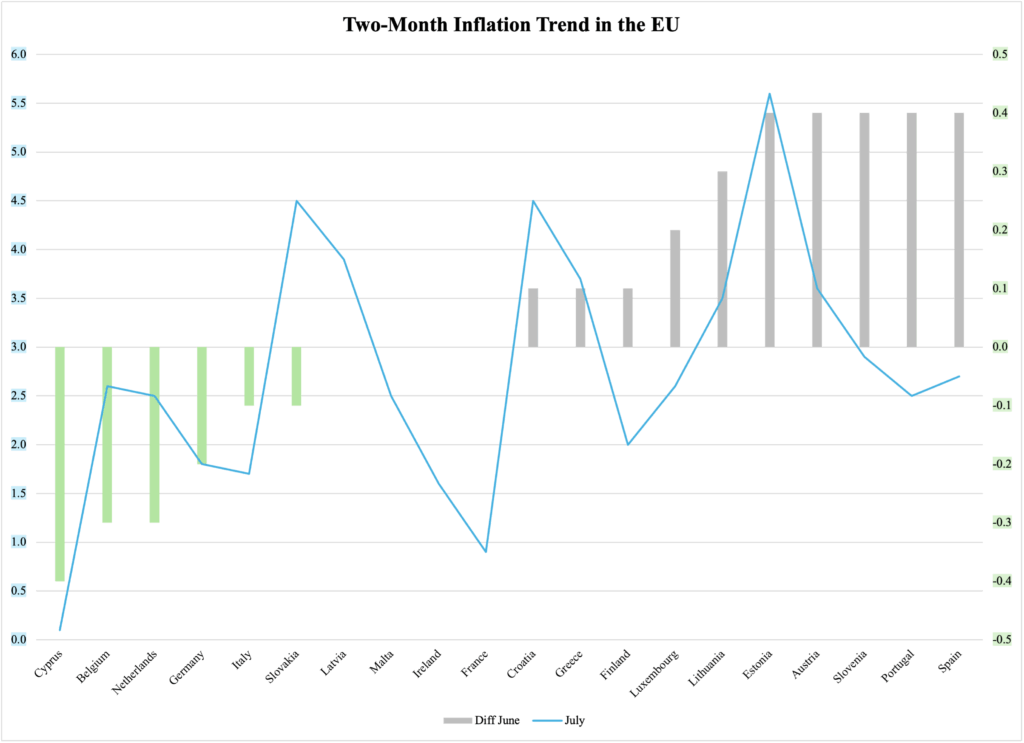

Compared to June, inflation fell in six states: Cyprus (-0.4%), Belgium and the Netherlands (-0.3%), Germany (-0.2%), and Italy and Slovakia (-0.1%). The inflation rate stayed unchanged in France, Ireland, Latvia, and Malta, while it increased by 0.4% in Austria, Estonia, Portugal, Slovenia, and Spain; by 0.3% in Lithuania; by 0.2% in Luxembourg; and by 0.1% in Croatia, Finland, and Greece.

Technically speaking, changes like these from one month to the next do not form a trend. However, there has been a noticeable spread in euro zone inflation rates over the past several months; a comparison between June and July figures is more of an illustration of this trend than a formal establishment of it.

If we look at the average inflation rates of the states with declining inflation and then compare that average to the group where inflation is rising, we find a significant difference:

Figure 2 illustrates this divergence. The blue line shows the individual member state inflation rates for July; the columns show the change in the inflation rate from June to July (with green representing a decline and gray an increase):

Figure 2

As mentioned earlier, the differences in inflation rates are problematic for the ECB. Things get quite a bit more serious if we add to those differences a trend where euro zone states are polarizing into two clusters, one with low and falling inflation and one where it is high and rising.

So far, the differences between the two clusters are not alarming. They may never become alarming either, but they are big enough at this point that it definitely affects ECB policymaking. However, the risk is that the ECB ignores the need of the seven euro zone states with the highest inflation rates to get help with bringing it down and instead tailors its monetary policy to the three biggest economies, where inflation is below 2%.

One reason why this risk is significant is simple arithmetic: the seven high-inflation countries have a combined GDP that is roughly one-tenth of that of Germany, France, and Italy together. For policymakers in a one-size-fits-all currency area, it is therefore tempting to ignore the small ‘outliers’ and leave them to fend for themselves.

I have no indications that the ECB is reasoning along these lines, but it is also a fact that the economic theory of currency areas prescribes that diverging inflation rates constitute a significant threat to the long-term sustainability of that currency area. It does not matter if the outlying members of the currency are small compared to the norm-setting big members; once differences in inflation reach critical levels, everything from financial speculation to labor migration will begin to move in patterns that destabilize the currency area itself.

I must repeat that the euro zone is nowhere near that catastrophic breaking point. However, the path to that point is opened by policymakers who do not take adequate countermeasures while there is still time. The euro zone has begun moving down that path. Only time, and ECB action or inaction, will tell if and when the currency area gets to a point where inflation disparity becomes an urgent problem.