Romania is notorious for its political instability, but it is also a country with significant economic potential. If the political leadership can unite around the right policy measures, the country could follow in the Hungarian footsteps with years of solid economic growth, rising prosperity, and completely manageable public finances.

Looking at Romania today, such a plan seems far away. The current government under Prime Minister Ilie Bolojan does not appear to have its priorities right. Rather than discussing how to stimulate economic growth, his administration is dead set on short-term fiscal measures to address a big budget deficit.

While understandable from the viewpoint of the European Union and its Stability and Growth Pact requirements for fiscal responsibility, the choice to try to address the deficit in isolation could easily backfire and make the macroeconomic situation worse.

On September 1st, Reuters reported that Bolojan’s government was pushing “a series of divisive public sector spending reforms and tax hikes” for a fast-track vote in parliament. The fast-tracking was bound to “face multiple non-confidence votes” as the opposition tries to throw a wrench into the incumbent government’s deficit-fighting policy measures.

According to StratNewsGlobal.com,

The cabinet approved a first package of measures, consisting mainly of tax hikes, shortly after it took power in late June, but the four parties in the ruling coalition have struggled to agree on cuts to bloated state spending.

As Reuters reported back in July, they have also struggled to stay united around the tax hikes:

The government has fast-tracked through parliament an increase in value-added tax, excise duties and other levies from August to prevent a ratings downgrade to below investment level and to unblock access to EU funds. … While all four parties in the government approved the increases, the Social Democrats, the coalition’s largest … criticised them on Monday.

Interestingly, Reuters explains that the Social Democrats thought this was the right time to start fighting for a progressive tax system. Under the auspices of wanting to “correct some of the absurd things” in the tax-hike package, the Social Democrats

supported replacing a flat rate of tax on income with progressive taxation instead of raising VAT, but the other parties did not support that and the tax authority has said it is not equipped to enforce it.

The very discussion about a progressive tax system shows how short-sighted the parliamentarily dominant Social Democrat party is. Furthermore, their insistence on hard-left policy measures fuels the impression of disagreement within the ruling coalition. Although it is not uncommon with brittle coalitions in a Romanian government, from an outside observer’s viewpoint, any acts that contribute to ripples of instability in government will hurt the Romanian economy at the exactly wrong point in time.

Bluntly speaking, thanks in part to the Social Democrats, foreign investors have good reasons to ask whether or not Prime Minister Bolojan can get any fiscal policies through parliament—even short-sighted ones that are focused on deficit reduction. That confidence is badly needed in Bucharest; as Romania-Insider.com reports,

Romania strives to bring the public deficit, 8.65% of GDP in cash terms (9.3% under ESA terms) last year, under 8% this year, versus an initial target of 7.1%. The first package of reforms is supposed to have achieved this year’s target while smoothing the way towards the 6.4% of GDP target set for 2026 under the 7-year fiscal consolidation plan sketched under the Excessive Deficit Procedure (EDP).

There are a lot of numbers being thrown around in the debate over Romania’s public finances. They can be confusing at times, especially when—as in this last case—two definitions of the same variable are stacked on one another. This is why I always use reputable, independent sources for quantitative economic information; producers of statistics like Eurostat, the OECD, and the UN National Accounts division use scientifically established methods and methodologies that guarantee their reliability.

In this case, Eurostat is the obvious contender to help us understand the Romanian economy and its public finances. Let us start with the latter and get an exact idea of what budget deficits the government in Bucharest has to deal with.

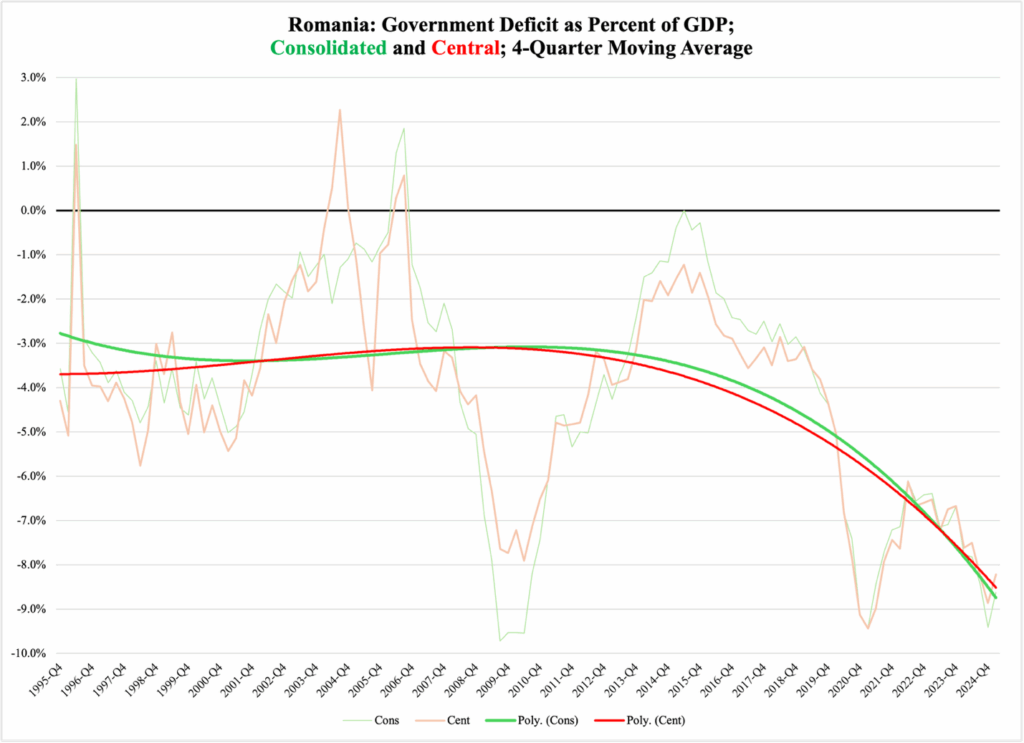

Figure 1 reports the budget deficit as percent of GDP for the consolidated Romanian government (green line), in other words, the sum total of the central (national) government, the regional and local governments, and the social insurance sector. It also reports the central government’s deficit as a separate number (red). The time period runs from the fourth quarter of 1995 through the first quarter of 2025.

The last time Romania enjoyed a budget surplus, central or consolidated, was 20 years ago—and the fiscal picture only gets worse with time:

Figure 1

With the deficit trend in Figure 1 as a background, it is easy to understand the political panic that surrounds Romanian fiscal policy.

The one thing Romania has going for it in terms of government finances is its debt. At 54.8% of GDP last year, it was below the 60% cap imposed by the EU’s constitutional fiscal rules. This is a uniquely low debt for an EU member state.

At the same time, with the deficits reported in Figure 1, Romania is rapidly approaching that EU cap. In 2015, its debt-to-GDP ratio was 37.7%; in 2005 it was 15.9%.

In 1995, Romania barely had any debt at all. The small pile of amount it had borrowed was only equal to 6.6% of GDP. Since then, every new government in the country has relied heavily—and from a fiscal viewpoint recklessly—on its ability to borrow money. Their spending has predominantly gone toward building, maintaining, and refining a traditional European welfare state.

As I have shown in articles about Germany and Slovakia, a welfare state that provides social benefits to people for the purposes of reducing economic differences among the population (in colloquial terms to ‘reduce income inequality’) will by necessity force the government into endless deficits.

Figure 2 tells us that Romania is no exception. It slices up total, consolidated government spending into the shares that go to each of the main spending categories. The red pie slices are all welfare-state spending programs, providing social benefits in one form or another; together they add up to 57.5% of total government spending.

Figure 2

There is one more positive aspect to Romania’s public finances. The welfare state is a bit smaller compared to most European countries, although it is vastly bigger than Europe’s leanest welfare state, the Hungarian (the only one in Europe below 50% of government spending). With a welfare state at 57.5%, the Romanian government is not yet quite as squeezed by the new, serious political conflict between the welfare state and national defense. The latter category, part of governments gray-marked essential functions, claims 4.2% of total government spending. This is on the high side for an EU member state.

When it comes to solving the budget dilemma, I cannot help thinking that Romania is lucky compared to its neighbor Bulgaria, which is about to enter the euro zone. By keeping its own currency, the Romanians have reserved for themselves the same monetary policy independence that only half a dozen EU states still maintain. This has allowed the Romanian central bank to let the leu depreciate against the euro, i.e., allow market forces to compensate for structural differences between Romania and the euro block of countries.

The most recent, and rather significant depreciation was the abandonment of a de facto fixed exchange rate to the euro in 2020. Intelligently, the Romanian central bank realized that its country would be hurled into a disaster if it prioritized the euro over the domestic economy.

By maintaining its own currency, Romania now has the ability to choose its foreign-trade strategy and attract foreign direct investments with the same high degree of independence that Hungary enjoys. This offers opportunities for economic growth that Bucharest can learn more about from Budapest; an exports-investment oriented macroeconomic plan would help Romania generate growth and decent household incomes, thus elevating people out of dependency on welfare-state benefits.

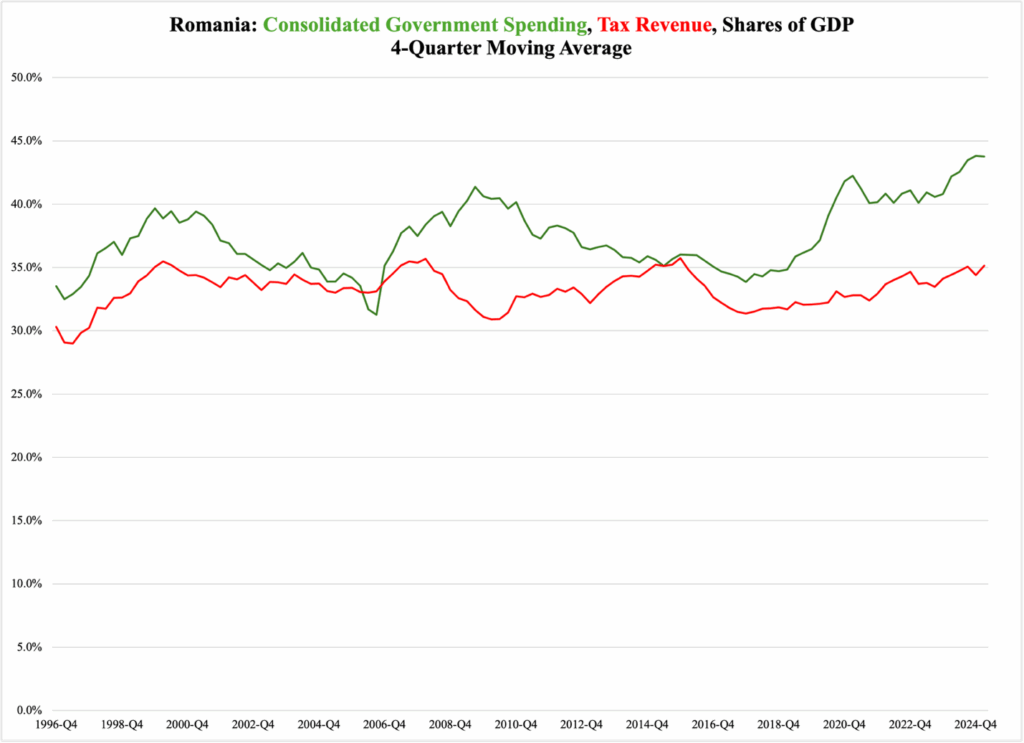

With a policy of this kind in place, the Romanian government can gradually cut down on the spending that accounts for 57.5% in Figure 2. What it should not do, in fact avoid at all cost, is higher taxes; the tax hike package passed by the parliament in June was a fiscal mistake. As shown in Figure 3, not counting that tax package, the total tax burden is only around 35% of GDP—a very competitive low ratio for Europe.

Figure 3

In addition to painting the picture of a government with a sound sense of tax restraint, Figure 3 also explains with clarity where the current fiscal problems in Romania come from. Over the past ten years, government spending has gone up by almost ten percentage points as share of GDP. This is economically unsound and fiscally unsustainable.

Again, Romania can still save both its economy and its government finances. A flexible exchange rate, restraint on taxes, and regulatory policies that invite foreign direct investment will lay the groundwork for Hungarian-style economic success. All it takes is for Bucharest to acquire the right dosages of economic common sense and long-term political determination.