In my analysis last week of the German government’s announcement that the welfare state has become unaffordable, I noted that other countries will inevitably follow in Germany’s footsteps.

It did not take long for Slovakia to emerge as the next scene for the welfare state’s demise. So far, no Slovak official has made any statements to that effect, but there is a dawning realization in Bratislava that they are going to have to place the welfare state on the fiscal chopping block.

Although the public debate remains scarce when it comes to specific ideas for welfare state cuts, media is not mincing words about the country’s dire fiscal outlook. On August 28th, The Slovak Spectator reported:

Slovakia’s political leaders are grappling with a growing financial headache as the country faces historically high costs to service its national debt. Official figures show that Slovakia has spent over €1 billion on debt interest payments since the beginning of the year—a sharp increase from previous years

The debt cost is expected to “hit a new record” for 2025, which is a problem in a country that has only had two quarters of consolidated (national, regional, and local governments) fiscal balance since 1999:

Figure 1

Generally, in Slovakia as well as elsewhere, any public debate over the government’s finances is almost always focused only on the national government. This is logical, given its importance in shaping government policy in many areas beyond strict fiscal matters, but it is a mistake insofar as fiscal sustainability is concerned. When it comes to government debt and taxpayers’ responsibility for the debt cost, it does not matter if the debt was accrued by cities, regional governments, or the national government.

As Figure 1 shows, the deficits in Slovak public finances have been allowed to build up for so long that the government has lost the ability to launch fiscally sound structural spending reforms. Such reforms take a long time to implement, and time is a scarce resource when the deficit is becoming an acute problem.

Bluntly speaking, the lack of attention to fiscal balance has pushed the Slovak government into a corner. As the news outlet HNonline.sk noted on August 12th, the prime minister and his cabinet only have two choices:

Whether it is the previously preferred increase in revenue in the form of tax measures, or the promised reduction in spending by streamlining the state, in both cases the new package will be painful for Slovakia.

The public conversation is focusing on cuts to social benefits, particularly for the “most solvent Slovaks”, as HRonline.sk put it back in July. A report from the Council for Budgetary Responsibility, CBR, expresses frustration over the government’s inability to maintain a clear trajectory toward fiscal balance. Referring to “European requirements for net expenditure growth”—fiscal rules from Brussels—as a guideline for budgetary improvements, CBR explains that only “a year has passed” since the introduction of national fiscal targets with reference to the EU requirements,

and the government is already relaxing the budgetary targets for 2026 and 2027 by 0.4-0.5% of GDP while at the same time putting off the target aimed at bringing the deficit below 3% of GDP

The government’s choices are not going to be easier going forward: the Slovak economy has lost all steam over the past year. In the first quarter of 2024, the country’s GDP grew by 3.3% adjusted for inflation; since then, it has tapered off precipitously:

With slow GDP growth comes slow growth in tax revenue. At the same time, there is nothing that slows down spending when GDP growth declines—on the contrary, in standard European welfare states, with entitlements profiled to primarily benefit lower-income households, there is an upward pressure on spending during periods of economic stagnation. A sluggish economy generates weaker household earnings, which leaves more people eligible for, and dependent on, tax-funded social benefits.

Figure 2

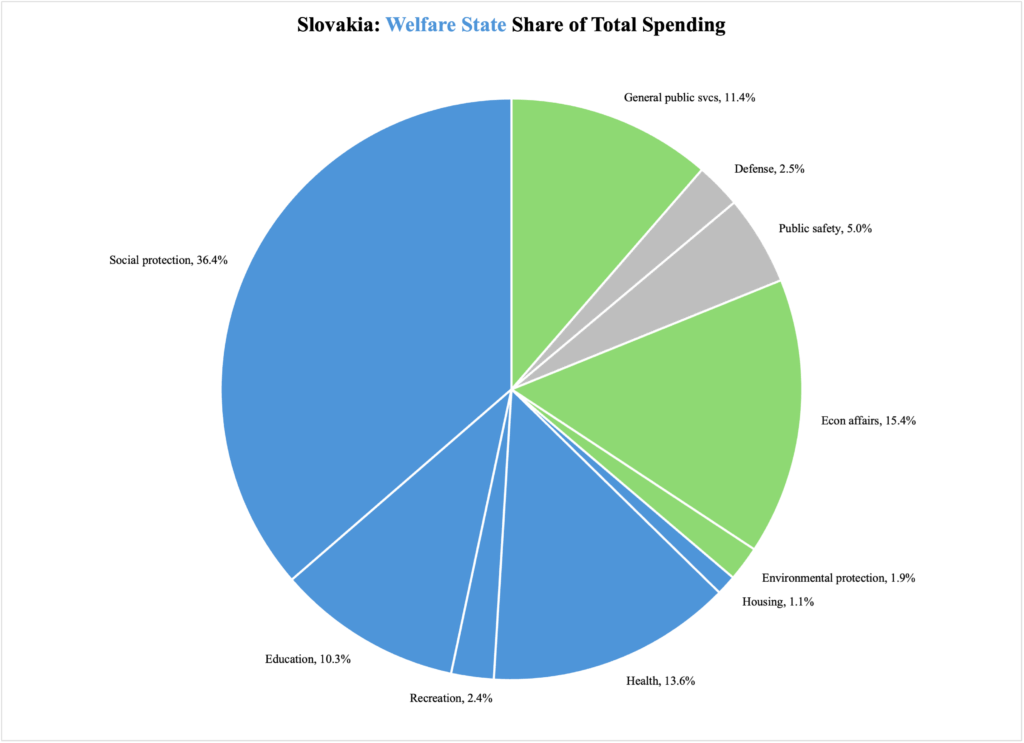

In total, the welfare state consumed €38 billion in 2023 (the latest year for which Eurostat has disaggregated, s.k. COFOG data, on government spending) which was split between the five categories as follows:

This two-thirds share of consolidated government spending contrasts starkly against the share spent on the core government functions: 5% on law and order and 2.5% on national defense, for a total share of 7.5%; the welfare state consumes 8.5 times more government resources than the core functions.

Figure 2 puts the Slovakian government’s fiscal dilemma on full display: cut the welfare state and face the wrath of those who lack the cash margin—or the desire—to lose those benefits; or make cuts to other functions, such as those marked green, where the same amount of euros will have more serious consequences due to the smaller total amount of spending.

Cuts to the welfare state are always difficult as they quickly lay bare ideological divisions. Some tensions of that sort are already visible in Germany after Chancellor Merz’s declaration that the welfare state is no longer affordable to the German economy.